I SAY I – SHE SAYS YOU YOU, AND ME?

Shifting Pronouns, Opaque Subjects, and Raising Voices in 1960s and 1970s Italy

Résumé

Cet essai provient de la transcription et de la réélaboration d’une séance de lecture collective proposée par Camilla Paolino au centre d’art Fri Art en février 2020 dans le cadre de l’exposition Dal momento in cui…., consacrée à Ketty La Rocca (La Spezia, 1938 – Florence, 1976). À partir d’un ensemble de textes poétiques en prose écrits par l’artiste italienne entre 1972 et 1974, Paolino aborde les concepts d’incommunicabilité, d’illisibilité, d’aliénation et de repli sur soi, qu’elle problématise du point de vue de plusieurs femmes actives dans la pratique de l’art et la production culturelle en Italie dans les années 1960 et 1970. La réflexion qui en découle relie l’expérience de La Rocca à celles de Carla Lonzi, Carla Accardi et des autres membres de Rivolta Femminile qui, à la même époque, endossant pleinement l’opacité de leurs postures radicales vis-à-vis de la culture et de la société, transformèrent leur position d’altérité en un terrain propice à la réalisation de leur subjectivation. La vision s’élargit alors et dérive vers l’étranger pour établir des liens spéculatifs avec les expériences de parias culturelles nord-américaines comme Valerie Solanas et Lee Lozano.

Texte

Una parola onnicomprensiva

irremovibile che detta

diventi materia dura.

Terra o pietra.

Che io la veda

la tocchi, poi.

Materia non risonante.

Carla Lonzi (Firenze, 20 ottobre 1953)

I speak here of poetry as the revelation or distillation of experience […] For women, then, poetry is not a luxury. It is a vital necessity of our existence. It forms the quality of the light within which we predicate our hopes and dreams toward survival and change, first made into language, then into idea, then into more tangible action.

Audre Lorde (1977)

When I first encountered the work of Ketty La Rocca, and notably her collages from the 1960s, I was troubled by my inability to grasp the meaning of the sentences the artist had composed by means of montage. I would read the wordings written in Italian, my mother tongue, and not understand their signification. A few weeks ago, while translating the few sentences surrounding us today into French, the same disabling feeling occurred to me: a sentiment of familiarity with the words, yet of estrangement from the way they were combined together. Engaging with the writing practice of Ketty La Rocca, in other terms, had the effect of alienating me from my own mother tongue, instilling a sense of dismay that brought to mind a short story by speculative fiction writer S. Qiouyi Lu, titled Mother tongues (2018). The story takes place in a dystopian future where it is possible to sell languages for money, at the cost of no longer being able to speak the language that has been sold. In this scenario, a Chinese woman is forced by economic constraints to trade her Mandarin, which is her mother tongue. By doing so, she suddenly loses the capacity to communicate with her mother and her daughter, together with the possibility to name and, therefore, think several aspects of reality. Therefore, she remains trapped in a state of incommunicability, alien to her own language, thinking and lineage.

Unsettled by the effect La Rocca’s writings had on me, I decided to further investigate this aspect of her work, focusing on questions of illegibility and incommunicability and on the condition of alienation these two impossibilities emerged from and, in turn, produced. Put differently, I set forth to explore the entanglement of alienation and language, as constitutive of the struggle to find a voice to speak with, allowing it to resonate from a position of alterity, such as the one occupied by Ketty La Rocca and other Italian women operating in the 1960s and 1970s within (or at the margins of) the field of art and culture1. To go into the heart of the matter, let us read two poetic proses written by Ketty La Rocca between 1972 and 1973, titled you you (1972-73) and e io? (and me?, 1973), as well as an untitled and unpublished piece of writing from 1974.

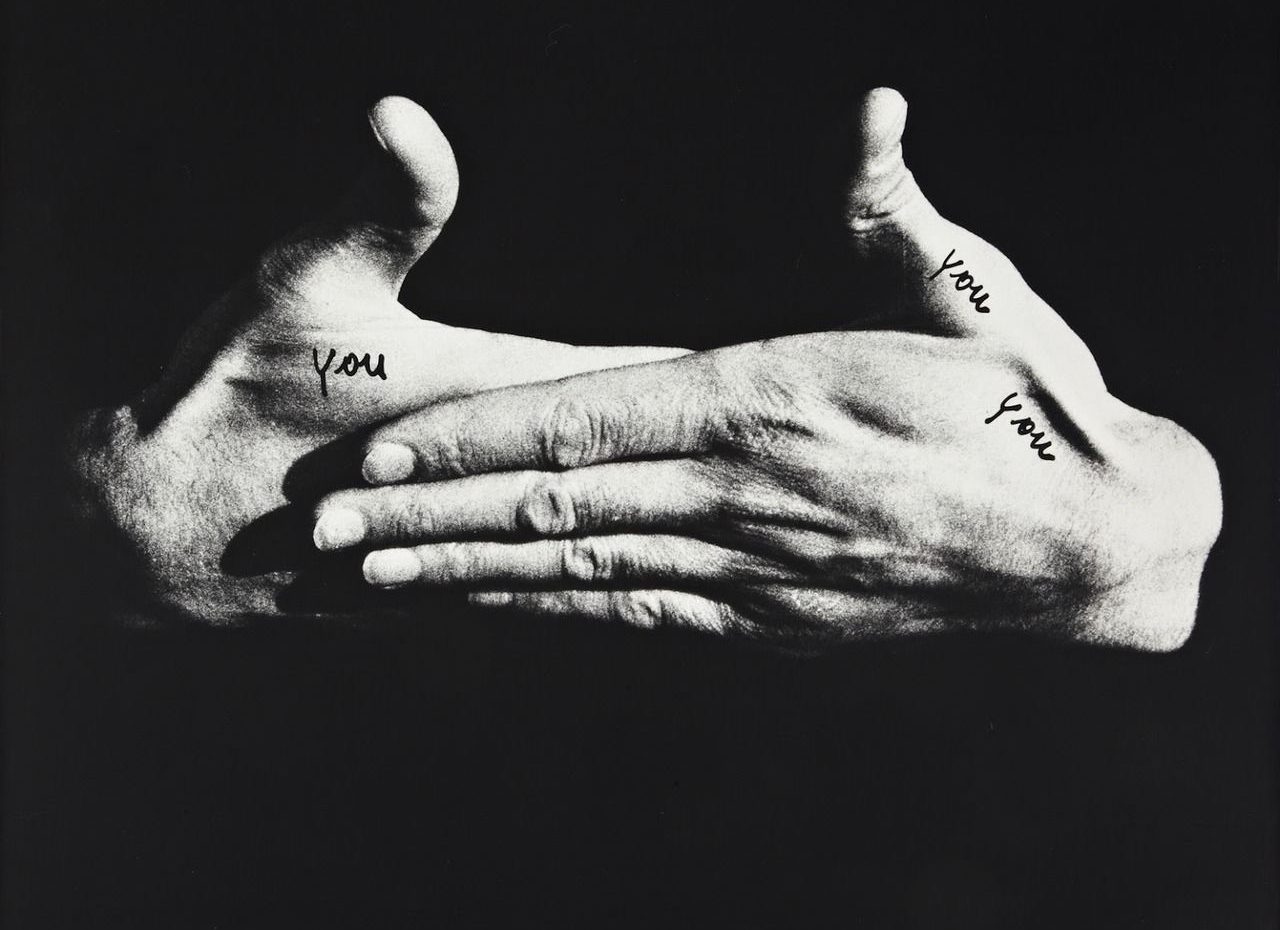

Reading n. 1: Ketty La Rocca, You you, 1972-1973

My work attempts to redeem the image to

itself / materialising its challenge to me-

taphor, a challenge already lost, but in a declared man-

ner, / indeed i don’t narrate, i limit myself to re-

tracing, drawing, writing the outlines with

the only possible sign: calligraphy / cal-

ligraphy, an alienating and partial moment that

already announces itself as historic, but nevertheless

unique, my only gesture there / “you you” ten-

ds to jam the visual and mental process /

and to reduce language to simple “bits”

of information / and make immediately clear the asym-

ptote of alienation / “you” also means

i, i have no alternatives, i save myself in my

own hysteria, with the unrepeatable gesture of wri-

ting myself by hand / in making microscopic liv-

ing the other than me / in being my own example of

alienation / but not of perversion / hence

my work is not the seat of my affec-

tions / it is not partial, therefore / but the denun-

ciation made against my stereotypes / it is not the warm

placenta to enwrap me / but cruelty like

new and unique will, / beyond this

strength one can do so much / as to say / “deer are

fast, Indians are fast, Indians are

deer”2 / and lose oneself in the narcissism of paralogia3.

You you comes as a dichiarazione di poetica (declaration of poetics), addressing Ketty La Rocca’s practice as a visual artist and her relentless and obsessive struggle with meaning, which unfolded in the midst of the general crisis of language and communication which spread in Italy during the boom years4. It hints at her artistic production from the 1970s, in which she combined visuals and language by intervening on the image with her own handwriting. Around the same time, she embarked on a process of disruption and progressive annihilation of articulate language in her writings, in order to reconfigure the linguistic tools at her disposal. The practice of linguistic alteration she engaged with stemmed from her feeling alienated by the dominant uses of language, which, in turn, led her to develop a language that was estranged and therefore estranging for the reader, and ultimately illegible. The opacity of her writing betrays a certain unease, but also a desire to commit to transformative radical practices in order to subjectify her voice.

In this specific poetic prose, Ketty La Rocca takes a basic linguistic unit, the pronoun you (the only infiltration of the English language within the Italian text) as a starting point, and sets the reader wondering about the identity of the hypothetical addressee she summons throughout the text. Then, she deconstructs it further. She claims that “you” also means “I”, that is to say that the writing subject and the addressee somehow coincide. The pronoun coincidence reveals a conflictual relation with the self: a self that is broken, schizophrenic, split in two. Ketty La Rocca is both herself and the other, as she is too often told to be; but instead of resisting the objectifying attribute, she embraces it and turns the “you” into the matrix which she at once identifies with and alienates herself from (Stepken 2017, 14). Put differently, she embodies the “asymptote of alienation,” which expresses her living condition in the form of a mathematical function whose graphical representation makes it possible to visualise the irreducible gap between the self and the other, or the liminal zone where her subjectivation is constantly negotiated. In such a polarised configuration, the two components that are constitutive of the alienated self, however close they may come, will never reunite.

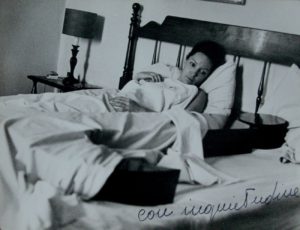

This polarized relation with the self was also performed in two works from 1970, where the artist lay in bed with the pronoun “I”, a three-dimensional anthropomorphized monogram in black PVC that was part of a body of works she had been producing since 1969. Stressing the contrast between self-affirmation and self-abstraction even further, these works set me wondering. Why was the relation to the self alienated for La Rocca? What position did she speak from?

Reading n. 2: Ketty La Rocca, E io? (And me?), 1973

my name, an insult, a disgrace, “unfit for the operative space:” the good guys crack up laughing, and what do i do, laugh!? it’s like laughing three times a day at the same joke, how fun. the bad guys ask: have you painted before? And you say no, that you didn’t do anything, that you “had other interests” excellent!! but then, you don’t know how, you let it out: i was a primary school teacher; the horror!! and the bad guys: what? you taught children to read, and me, blushing and lying: but using logic blocks, that leaves them perplexed for a couple of seconds because they think it must be stuff that comes from America, you never know, better be careful about badmouthing it.

where are you from? from Florence, but i wasn’t born there, dumb clarification, they still manage to forgive someone who is actually Florentine, but someone who chooses to go there… and so you correct yourself, badly. it was a move, yes, the school. ah! the kids’ school.

and you live only there, in Florence?

and me, such a boor, it never crossed my mind that one could live in two or three or seven places, i answer: yes, but i travel… (sic) exaggerated! by this stage, you would drop to your knees; forgive me! forgive me! if i have been a primary school teacher and without logic blocks, but rather using chalk and blackboard and no audio-visuals, but now i travel: train 297 departure 6:05am arrival in Milan 10:05am departure 7:55pm arrival in Florence 11:30pm and to bed. that’s it, the bad guys stare at you, meaning: but that’s not travelling, and me? i’m perfectly aware that that’s not travelling, that travelling means going to Rimini, in the summer and without schedule, just changing at Bologna, to go swimming.

shut up now. i get my things together in a rush and clumsily, clumsily to put it mildly, drop? half the stuff on the floor, slipping all over the place, you pick it up, bunching together the 18/24 sheets and the few 24/30 all of them already crumpled. and him: take care and you, not even too convincedly: drop dead.

and me?

i took my skirt off long ago, not to speak of a pleated tartan skirt, now just plain trousers, chinos, not the old-style, short ones, but the modern ones in cornflower blue color, old sugar this time, baggy, dragging on the ground, never new! and lipstick? i don’t want to think about it, i really liked wearing it; i did a test, if i wore lipstick they would ask me if i had painted before. association of ideas as subtle as that of a police officer interrogating the “aforesaid;” what do i do? i hit him or i tell him that, as associations go, he could have made one with another part of the body which doesn’t have lipstick, but is the reason why it’s worn.

and me?

nice jumper! ah yes! i bought it at Upim. the bad guys, complacently: sometimes you can find fabulous things even there! and you who have sent one you liked packing because in front of one of your works he had said fabulous and, poor thing, he will never understand how i, who am not a great beauty; but what can i do, i begin to scratch simulating a graceful gesture, if you could call it graceful: an old outbreak of eczema on the elbow. but i have to learn: one buys jumpers in the shops, the little ones with lots of rags at just 28’500 liras each, of course, you can’t expect an armful of rags for that price; a jumper like a camisole, the one that nobody wears anymore and now is worn on top.

again with affectionate metalanguage5.

This second poetic prose, overflowing with awkwardness and distress, provides hints of biographical information, as well as regarding the context in which the artist operates. She has moved to Florence, a city that apparently is not considered to be an epicentre, but rather a peripheral reality, according to the standards of the Italian contemporary art world. She has limited financial means, which is the reason why she does not travel and shops at Upim, a supermarket that appears in the works of other women artists active in Italy at the time, which is very telling of the way certain forms of labour (such as shopping for groceries) were still distributed according to gender6. She has been teaching in a primary school, yet another form of labour performed almost exclusively by women which was highly devalued at the time (“the horror!!”)7. And she is a woman immersed in a men’s reality: the monological world of art and culture8. To gain recognition in such a domain, she is forced to give up her “skirt” and “lipstick”, together with her birth name (Gaetana), which in the very beginning of the text she defines as “an insult, a disgrace”. A name that has been labelled as “unfit for the operative space” by someone else (as we infer from the quotation marks framing the sentence)9.

But who is this “someone else,” who keeps intervening as a sort of voiceover, aggressively interacting with the writing subject? On the one hand are the “good guys”, who seem to be rather purposeless for the aims of Ketty La Rocca’s reflection and soon leave the picture. And on the other are the persistent “bad guys”, who stay on and give her a hard time. They are the Art system guys, eminent voices from the world of culture, as suggested by the meticulously chosen lexicon which composes the quote “unfit for the operative space,” a wording that resonated widely, at the time, in the jargon of the so-called “critichese” (or the language of Italian art criticism). They will not accept her or take her seriously as an artist, because she lives in Florence, buys clothes at Upim, and was an elementary school teacher. But above all, because she is a woman. Against this undifferentiated backdrop of disembodied, eminent, voices, the chorus of the “bad guys” entitled to judge and to perform a sort of god trick (Haraway 1988), a question keeps returning with insistence: e io? (and me?).

Back then, being a woman in the art world was an uncomfortable place to occupy and to speak from, as Ketty La Rocca testifies in a letter addressed to American art critic Lucy Lippard, written in the summer of 1975: “Still, in Italy at least, being a woman and doing my job is incredibly difficult” (Saccà 2005, 143. My translation). In fact, the women engaging in artistic practices on the peninsula’s art scene at the time were few and far between, and those who did had a hard time being recognized by critics, collectors, institutions and even their fellow artists10.

In the same letter to Lucy Lippard, La Rocca mentions a text she has written reflecting on the condition of being excluded from language and hence deprived of a voice to speak out with. It is most likely the following poetic prose, written in 1974:

[for women, this is not a time for statements: they have too much to do

and then they would have to use a language that isn’t theirs, within a

language that is as alien to them as it is hostile

therefore all i can say with an unusual intimacy, like a space that is generous

and desolate, but free, is that, code in hand:] as far as i’m concerned, i have

all the defects of women without having their qualities: a negative feminine,

like others,

expropriated of everything except those things that no one wants,

and there are many, although a bit to be sorted out,

the hands, for example, too late for women’s skills,

too poor and incapable to continue hoarding,

it is preferable to embroider with words and accelerate the universal paranoia,

and to the first imbecile who thinks he has discovered America “it must be

for a marriage turned sour,” yes, indeed, precisely for this reason

he will never be able to understand11.

The struggle of having to talk in a language that is “alien” and “hostile” to the speaking subject is a core question here too, as it is the sense of inadequacy and dismay one may feel when not conforming to one’s ascribed identity. That is to say, for someone like Ketty La Rocca, when resisting the definition of femininity which describes women in the language of the oppressor. In fact, according to the phallogocentric definition of what a woman is, Ketty La Rocca isn’t one. She is an artist. As such, she embodies what she calls the “negative feminine,” a nonplace that is the only site she can speak from, at the risk of being perceived as opaque, illegible12.

To better understand this position, I would like to bring into the picture the experience of two other women operating within the Italian artistic and cultural field in the same years: Carla Lonzi and Carla Accardi.

More or less at the time when Ketty La Rocca began producing collages such as La cultura che non vive or Io sono Peter, artist Carla Accardi presented her work in a solo-show at the XXXII Venice Biennale. The year was 1964. Carla Lonzi, who at the time worked as an art critic, wrote the presentation text to her friend’s exhibition13. In the text, in order to describe the position Carla Accardi occupied as a “woman artist,” Lonzi drew a parallel between her friend and Mrs. Winnie, the protagonist of Samuel Beckett’s play Happy Days (1961). Mrs Winnie is a woman trapped up to the waist in a pile of sand, thus symbolising the condition of paralysis14. The comparison invites the reader to reflect on Accardi’s posture as a woman caught in a framework strongly dominated by patriarchal logic: an Art system that still tended to exclude women’s subjectivity, pushing women to the margins or trapping them into objectifying positions. As Lonzi and Accardi lucidly pointed out a couple of years later in a conversation published in Marcatré, “Art has always been a men’s kingdom. As for us [women], as soon as we step into such a masculine field as the one of creativity is, we feel the need to unmask all prestige surrounding it and making it inaccessible”15. And this is precisely what they did.

Soon enough, this awareness led the two women to embark on a journey that resulted in their writing, together with Elvira Banotti, the first Manifesto di Rivolta Femminile and forming the homonymous neo-feminist group and the related publishing house Scritti di Rivolta Femminile, both founded in Rome in the spring of 1970.

After approximately three years of joint struggle in the ranks of Rivolta Femminile, the paths of the two Carlas split. Accardi continued working within the Art system, gradually affirming herself as an artist. Lonzi, on the other hand, dropped out of the art world and the sphere of institutionalised culture, instead devoting herself entirely to feminism, la sua festa (her party) (Lonzi 1978a, 44). For the purpose of our reflection, let us follow Carla Lonzi’s path, as it will help us come full circle and return to Ketty La Rocca.

In 1970, Lonzi felt compelled to withdraw from the art scene for good. At the root of this decision lay her intolerance regarding the marginalising dynamics at work in the fields of cultural production, where, for centuries, men had been granted the status of artists and geniuses, whereas women were relegated to subsidiary roles: the artist’s companion, his model, his muse (that is to say, a symbol), and ultimately, the passive spectator of his “prestigious” gesture16. In fact, she chose to withdraw from patriarchal culture in general, for she deemed it to be a monological site of oppression, forcing women into silence and into the ontological state of non-being. Carla Lonzi and the other members of Rivolta Femminile refused to inhabit such an annihilating position and performed an atto di incredulità (act of incredulity) aimed at those who theorised women’s inferiority, rejecting all institutions: culture, customs, traditions, history, family, sexuality, and even language (Lonzi 1977, 45). All this was to be abolished for the tabula rasa of culture to be accomplished17, clearing the path for women to emerge at last as subjects, thus disrupting the course of history: the soggetto imprevisto (unpredicted subject) notoriously “prophesized” by Carla Lonzi (Boccia 2014, 61; 73-77).

Unlike the coeval women movement, which at the time was struggling for emancipation and equal rights within the patriarchal order, Rivolta Femminile aimed to muoversi su un altro piano (move on a different plane) (Lonzi 1977, 54), or porsi fuori, in other words, to situate themselves outside of such an order18.

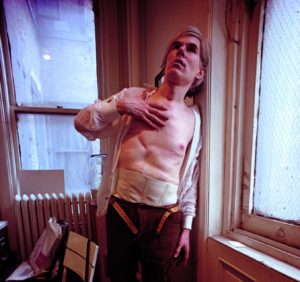

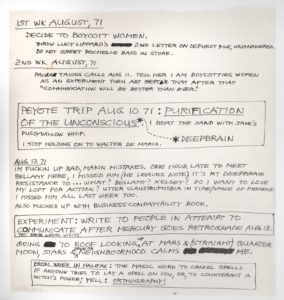

Carla Lonzi, in particular, while dismissive of the movement, seemed to validate presumably irredeemable stances, such as that of Valerie Solanas: a writer from New Jersey, author of the SCUM Manifesto (1967) and leader (and only member) of the Society for Cutting Up Men, who, on June 3rd, 1968, shot Andy Warhol three times in the abdomen19. She was sentenced to prison and, after being diagnosed as mentally alienated, she was hospitalised and gradually faded away from New York’s social fabric , discretely and unnoticed20.

I became curious about the relationship between Carla Lonzi and Valerie Solanas when I came across a footnote (number 121) in Giovanna Zapperi’s book Carla Lonzi. Un’arte della vita (2017). This finding opened up a speculative horizon on the possible connections between the experiences of these two women. The footnote recounts that Lonzi and Solanas exchanged letters (hampered by the fact that Lonzi did not speak English) concerning the unauthorized Italian translation of SCUM Manifesto. In her letters, Solanas also complains about the fact that the Italian journal L’Espresso erroneously released the news of her death, a rumor which had become widespread because a few years after the scandal and its institutional and juridical consequences, Solanas had become invisible and was even believed to be dead by her own relatives21. Scandalo e morte civile di una Chelsea Girl (scandal and civil death of a Chelsea Girl), as Anne-Marie Sauzeau phrased it (Sauzeau 1976, 62. My translation).

Just before disappearing for good from the social fabric, Solanas was inflicted an ultimate humiliation: she was mentioned in the news (in the New York Times and the Village Voice, among others) as Valeria Solanis, and labelled “Andy Warhol’s actress”, for having played a minor role in one of Warhol’s movies entitled I, a Man (1967). Valerie Solanas, the writer, the author of SCUM Manifesto, the founding member of the Society for Cutting Up Men no longer existed. In her place stood this fictional character, Valeria Solanis, Andy Warhol’s actress, yet another individual to be added to the list of women who lost their names and identities throughout Art History22.

In fact, some exponents of the National Organization of Women (NOW) did try to recover and recuperate her misdeed right after Solanas was imprisoned, but this only made her furious as she sensed the danger of being reduced to a model, a symbol, an ideology, thus rendering her gesture comprehensible, intelligible, and even acceptable23. That is to say, the danger of being brought back inside the system, a place Solanas could not inhabit for she was an outlaw and an outcast: standing outside of ideologies, politics, culture.

In the book La presenza dell’uomo nel femminismo (1978), Lonzi relates her rejection of art and culture to Solanas’s extreme gesture of shooting Warhol, who at the time was already considered as an icon by the international art world. However, there was one major difference between Lonzi and Solanas: The latter performed her gesture in solitude, an operation entailing progressive marginalization, misery, and madness (Zapperi 2017, 228-229). In Lonzi’s words, “Solanas accepts the urgency and risk of a solitary condition” (Lonzi 1978b, 141. My translation). On the contrary, Lonzi’s withdrawal was initially performed as a collective act: Rivolta Femminile stood by her and this was the sine qua non for the subjectivation of all women involved in the group to take place. In fact, according to them, a woman could only become a subject in relation to another woman who recognised her as such, allowing her to exist outside the objectifying roles she had been trapped in up until then24. This is why women’s destinies are deeply entangled and their relationships are what protects them from madness as their consciousness raises25.

But even for Carla Lonzi this was going to change.

The Manifesto di Rivolta Femminile, written in 1970, together with Accardi and Banotti, opens with a quote by Olympe de Gouges questioning the (im-)possibility for women to merge and co-operate together as a unique body: “Will women always be divided from one another? Will they never form a single body?” (1791). The pronoun “we” is the writing subject and recurs as a refrain throughout the manifesto. As years went by, however, Lonzi’s posture became more and more radical, growing so intransigent as to end up having an impact on her affects. In 1973, she broke off her relationship with Carla Accardi, and a year later, with Suzanne Santoro. Then, with Ritva Raitsalo and all the other women artists of Rivolta Femminile, because they wanted to continue “compromising” themselves by remaining entangled in the field of art and culture.

In 1977, Carla Lonzi composed a second manifesto, titled Io dico io, where the writing subject is no longer the collective “we”, but the individual “I”, and the antagonist is no longer patriarchy itself, but all women who label themselves as “feminists” and yet choose to remain within culture, tacitly accepting the ideological and epistemological foundations on which it rests. This shift from “we” to “I” shows how radical her act of withdrawal was, to the point of affecting and morphing the way she constructed and positioned herself as a subject. Hers was an insidious process of becoming, which grew more and more opaque. It somehow recalls the experience of an American artist, Lee Lozano, who also dropped out from art and culture in the spring of 1970, and, one year later, stopped talking to women. This self-imposed constraint seems to echo – and yet turn on its head – the closing line of the first Manifesto di Rivolta Femminile, “we communicate only with women,” and has been commonly ascribed to a psychological breakdown, or some sort of mental alienation. Although her name was Lee Lozano, as she faded away in the attempt to forge her own radical subject position, she went simply by “E,” making clear that the artist she had been had ceased to exist to the world26.

Carla Lonzi’s drop-out, which coincided with the refusal of any codified identity or activity in general, also came with the heavy price of erasure. It was an intellectual, political, and existential project, which implied the obligation to embrace the condition of alienation deriving from it, together with the disorientation and loss of coordinates one experiences when stepping out of one’s role (Boccia 2014, 31). As Giovanna Zapperi writes, “What Lonzi is doing is destined to remain incomprehensible at best, removed or deleted at worst, as if it never even existed” (Zapperi 2017, 231. My translation). The nonplace she felt compelled to inhabit was indeed irredeemable within the framework of institutionalised culture and society at large, and such a positioning rendered her politically illegible and socially inexistent, as formulated by Claire Fontaine throughout her ongoing reflection27. The worst of it was that Lonzi was aware of the illegibility of her position and the destiny of solitude it entailed, as expressed by the deep anguish pervading the pages of her diary Taci, anzi parla (1978). In the diary, published one year after the second manifesto Io dico io, one can read the frustration she felt at failing to find interlocutors, as well as the danger she sensed of rendering her own voice inaudible and of precipitating herself into that state of non-being which is the antechamber to madness28.

However, she did not surrender and kept on searching and writing. Because, as Maria Luisa Boccia notes, “In Carla Lonzi’s feminism, writing is the only way to remain suspended upon the void, to escape the strong grasp of culture […] It allows to speak and to call yourself a subject in a full and potent way [Io dico io!], without letting this work of words translate/betray subjectivity by trapping it into prescriptive contents” (Boccia 2014, 82-83. My translation). Writing, when practiced in a way that is detached from culture and from its dictates and prescriptions, indeed allows for a constant re-positioning, or for a continuous subjectivation beyond fixed identities29. Yet, to these ends, it is an operation to be performed in a language that is different from the language of patriarchy, the primary site of oppression and repression of all otherness (Casavecchia 2016): this language is therefore doomed to remain unreadable. It is no coincidence that Carla Lonzi’s first approach to writing occurred through poetry, which Boccia identifies as the direct antecedent to her feminism: poetry is her “challenge to signification”30.

To come full circle and conclude, I have been driven by shifting pronouns to weave together the experiences of Ketty La Rocca and Carla Lonzi, via those of Valerie Solanas and Lee Lozano, for I read them all as different variations of the same commitment to affirm and declare oneself as a subject by exceeding the normative framework of culture. That is to say, by dropping out of a site of oppression where the position as subjects has always been denied them. With them, alienation is no longer to be understood as a condition to pathologize, criminalize, or remove, but rather as a fertile ground for transformation, where new subjectivities can emerge. With them, illegibility is no longer to be ascribed to the illiteracy of those who speak/write, but rather to the unreceptiveness of those who are supposed to listen/read, but are too accustomed to the speech/text of power to be able to do so. Despite the irrefutable differences of their positions (for Lonzi withdrew from art and culture only to embrace feminism; Solanas and Lozano rejected it all, especially the latter; whereas La Rocca didn’t get openly involved with feminism, and kept engaging with art to the point of becoming a well-established and recognised artist), all four embody the struggle to become subjects, moving from the nonplace they inhabited and giving voice to the “negative feminine” outlined by Ketty La Rocca in 1974. And they did so primarily through language and writing, accepting the risk of remaining illegible.

Notes

- As Barbara Casavecchia has highlighted, the Italian 1960s and 1970s resounded with a plurality of voices raised by a generation of women who were eager to break free from the semiotic and silencing constraints of the patriarchal order, overburdened with the oppressive legacy of the fascist family code and catholic morality. Using language as the battlefield for their semiological guerrilla to take place, these women voiced the crucial need to expand their ability to generate audibility, while challenging the language of the oppressor. For more on this, I refer the reader to Barbara Casavecchia, “1966 and Thereabouts: Call Girls, Riot Grrrls in Evolution, Poetry and ‘Missing Language.’ Ketty La Rocca, Lucia Marcucci, Giulia Niccolai,” in Ennesima: The Image of Writing. Gruppo 70, Visual Poetry and Verbal-Visual Investigations (Milan: Mousse / La Triennale, 2015); and Barbara Casavecchia, “Taci, anzi parla,” South as a state of mind 7, dOCUMENTA14, no. 2 (spring/summer 2016): https://www.documenta14.de/en/south/463_taci_anzi_parla.

- The stereotyping tendency Ketty La Rocca tackles and denounces throughout her poetic proses does not relate to gender constructs only, but also to racist biases and colonial legacies, still widespread in the common parlance of the time. May the reader bear this in mind while reading the present syllogism, as well as other discursive elements one can find in the following poetic proses.

- First published in Lea Vergine, Body Art e storie simili: Il corpo come linguaggio (Milan: Prearo Editore, 1974), now in Lucilla Saccà, Ketty La Rocca: I suoi Scritti (Turin: Martano Editore, 2005), 93. My translation.

- La Rocca’s relentless research on language and her struggle with signification are couched within a larger historical and sociocultural framework, which had witnessed the insurgence of a plurality of voices and positions addressing the crisis of language and communication breaking out in the Italian boom years, with the rise of technological consumerism and the spreading of mass media and commercial information regimes. For more on this, and on the relationship between Ketty La Rocca and Gruppo 70, or other exponents of the coeval literary and poetic Neoavanguardia, I refer the reader to Lucilla Saccà, Ketty La Rocca: I suoi Scritti, 11-21; and Lara Vinca Masini, Ketty La Rocca (Florence: Edizioni Carini, 1989), 5-8.

- Lucilla Saccà, Ketty La Rocca: I suoi Scritti, 86. My translation.

- An iconic work I feel compelled to mention in this regard is Nicole Gravier’s Prima di passare alla Upim, Mythes et Clichés. Fotoromanzi, from the series Attesa, 1976-1980.

- The experience of Ketty La Rocca mirrors that of other Italian women artists who were also school teachers at the time. This was the case of Maria Lai, for instance, whose teaching experience was partially transposed into her art practice; as well as Carla Accardi and the filmmaker Adriana Monti, who brought their feminist practices and political commitment into the classroom, embracing the principles of feminist and anti-authoritarian pedagogies. On the one hand, the commonality of this experience was symptomatic of women’s inability to access other occupations, which was still the prevailing reality in 1960s and 1970s Italy. On the other, La Rocca’s embarrassment at performing t pedagogical labour and the reaction of her interlocutors suggest that the teaching job was devalued and deemed of secondary importance at the time.

- The binary opposition between women/men reflects the discourse mobilized at the time by a few women struggling to affirm themselves as cultural producers within the Italian Art system of the 1960s and 1970s. I invite the reader to situate the categories of “woma/en” and “ma/en” and the binarism these entail within such a specific historical context at any time these are employed in the following text.

- The fact that La Rocca opens this poetic prose with a reflection on her birth name (implicitly suggesting that she has been urged to change it in order to gain credibility as an artist) evokes the long-lasting struggle women had to face throughout the history of art: operating and being recognized as artists yet maintaining their own names. In this regard, I feel compelled to mention Barbara Casavecchia’s studies on the subject. Taking as a starting point Emily Mary Osborn’s painting Nameless and Friendless (1857), Casavecchia retraces the historical trajectory of the issue, mentioning artists such as Laura Hertford, who used to sign her works with initials only, thus creating a nameless production, or artists who had to wear men’s clothing (Rosa Bonheur) or men’s names (Adele d’Affry a.k.a. Marcello), in order to be considered “fit for the operative space”. Barbara Casavecchia, “Senza nome. La difficile ascesa della donna artista,” in Antonello Negri (ed.), Arte e artisti nella modernità, (Milan: Editoriale Jaca Book SpA, 2000), 83-108. The problem of naming returns and is further addressed below.

- In the Art system, in particular, despite their increasing involvement in art-making, women kept facing difficulties in having their work exhibited in galleries, museums, and other institutional venues, as well as in gaining the interest and trust of collectors, and the recognition of their fellow male artists. For a rather detailed cartography of the situation, based on the testimony of artists such as Carla Accardi, Giosetta Fioroni, Ida Gerosa, Cloti Ricciardi, and Suzanne Santoro, I refer the reader to Marta Seravalli, Arte e femminismo a Roma negli anni Settanta (Rome: Biblink editori, 2013), 143-152.

- Lucilla Saccà, Ketty La Rocca: I suoi Scritti, 96. My translation.

- For more on Ketty La Rocca’s reflection on “women’s condition” and on the ontological constraints it entailed within the sociocultural framework she inhabited, I refer the reader to Lucilla Saccà, Ketty La Rocca. I suoi Scritti, 13. Part of the artist’s reflection also took the form of then-unpublished poems, now published in the aforementioned book by Lucilla Saccà, as well as a play entitled La storia che ha commosso il mondo, published in Quaderni di Tèchne, suppl. Tèchne, no. 3-4 (March/April, 1970).

- Carla Lonzi, “Carla Accardi,” XXXII Biennale d’Arte di Venezia (Venice: Ente Autonomo La Biennale di Venezia, 1964; Italia, sala XLIII), 114-115, now in Carla Lonzi, Scritti sull’arte, eds. Lara Conte, Laura Iamurri, Vanessa Martini (Milan: et al./Edizioni, 2012), 372-373.

- Happy Days was staged for the first time at the Cherry Lane Theatre in New York in September 1961. The script was promptly translated into Italian by Carlo Fruttero and published in Samuel Beckett, Teatro (Turin: Einaudi, 1961), 209-252.

- Carla Accardi, Carla Lonzi, “Discorsi: Carla Lonzi e Carla Accardi,” Marcatré (23-23 June 1966), 193-197, now in Carla Lonzi, Scritti sull’arte, 471-483.

- As has been sharply pointed out on several occasions by Carla Lonzi, Carla Accardi and the other women of Rivolta Femminile. Their reflection on this sexual division of labor reducing women to passive or subsidiary roles within the creative process was first outlined in Carla Accardi and Carla Lonzi’s “Discorsi: Carla Lonzi e Carla Accardi” (1966), and further elaborated both within the collective framework of Rivolta Femminile (“Assenza della donna dalle momenti celebtivi della manifestazione creativa maschile,” 1971), and individually, by Carla Lonzi in her diary Taci, anzi parla. Diario di una femminista (1978) and in Vai pure. Dialogo con Pietro Consagra (1980).

- Once the blind trust in all these institutions, myths, and sets of beliefs collapses, all prefabricated identities dictating what a man and what a woman should be (those same identitarian models according to which Ketty La Rocca stands as a “negative feminine”), can be dismantled and dismissed. This is the process of deculturizzazione (deculturization) theorized by Carla Lonzi in “Sputiamo su Hegel,” in Sputiamo su Hegel, La donna clitoridean e la donna vaginale e altri scritti (Milan: Scritti di Rivolta Femminile, 1977), 47.

- As Roberto Lambarelli has put it, Carla Lonzi’s porsi fuori upsets the Hegelian dialectical method because she does not place herself in antithesis to the existing system, but moves on another plane, which is neither the plane of dialectics, nor of equality, but of difference. This also means moving beyond the form of modernity which stems from the Marxist class dialectic, whose driving force always is the struggle for power. In the framework of institutional art criticism, where exponents of the avant-garde such as Germano Celant and Achille Bonito Oliva reaffirmed the dialectical logic by setting themselves against the critics of the previous generation, Carla Lonzi’s choice to place herself “outside”, by practicing feminism and separatism, determines a short-circuit and turns out to be irremediable. Roberto Lambarelli, “Anne-Marie Sauzeau verso Carla Lonzi e ritorno,” Arte e Critica (2013).

- Anne-Marie Sauzeu translated SCUM Manifesto in Italian in 1976, which was published by the Edizioni delle donne di Roma (Rome). As reported by Barbara Casavecchia, SCUM Manifesto was instantly recuperated by the prog-rock band AREA, which released a hit containing bits of the manifesto read by Demetrio Stratos: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K0IjIkXCa1w. Barbara Casavecchia, “Taci, anzi parla”.

- Solanas served three years in two different prisons, during which time her publisher Maurice Girodias published SCUM Manifesto. After her release from prison, she was admitted to five different psychiatric hospitals, which led to her “civil death”. For more on this, I refer the reader to Anne-Marie Sauzeau, “L’amazzone solitaria,” in Valerie Solanas, S.C.U.M. Manifesto per l’eliminazione dei maschi (Rome: Edizioni delle donne, 1976), 62.

- The entire correspondence, from 1977 and 1978, is preserved in the Fondo Rivolta Femminile of the Fondazione Jaqueline Vodoz e Bruno Danese in Milan. Giovanna Zapperi, Carla Lonzi. Un’arte della vita (Rome: DeriveApprodi, 2017), 296-297.

- On the subject of names, I refer the reader to footnote 8. Regarding the definition of “Art History” as a dominant, canonic, and monolithic discipline, as opposed to the multiple notion of the “histories of art,” denoting a plurality of narratives, I refer the reader to Griselda Pollock, Vision and Difference: Femininity, Feminism and Histories of Art (New York: Routledge, 2003), xviii.

- When Solanas was arrested, the National Organization of Women (NOW) split into two factions: one side, led by Betty Friedman, disavowed Solanas’s gesture, denouncing it as a case of deviant ideology; the other, with Ti-Grace Atkinson in the lead, offered solidarity to the inmate, who was considered an example of “wild politics”. Anne-Marie Sauzeau, “L’amazzone solitaria,” 62-63.

- To unpack this concept a little further: Lonzi’s porsi fuori, or drop-out, was not supposed to coincide with isolation, but rather with a group practice, or a collective transformative event: relationships, correspondence, and mutual recognition were considered as essential premises for women’s dis-identification from predefined roles and subjectivation. As Lonzi put it, no consciousness can be raised without another consciousness raising, as one’s way out and the other’s way out are intertwined. Carla Lonzi, “Mito della proposta culturale,” in La presenza dell’uomo nel femminismo (Milan: Scritti di Rivolta femminile, 1978), 141 (my translation).

- As Carla Lonzi put it, the lack of responsiveness produces on those who endure it the effect of not existing, of being a living mistake. Carla Lonzi, “Mito della proposta culturale,” 148 (my translation). Relationships and responsiveness are hence what protect women against madness: a fate Solanas did not escape, finding herself experiencing her political awakening in total solitude. As Maria Luisa Boccia points out, madness corresponds to a condition whereby, if one does not correspond to the ascribed identity (for instance, femininity), one feels sick and is perceived as such, as if lacking in mastery and a sense of oneself. Whenever women have discarded the identity ascribed to their gender, madness, neurosis, psychosis, hysteria, and disease in general have been attributed to them. For more on this, I refer the reader to Maria Luisa Boccia, Con Carla Lonzi. La mia opera è la mia vita (Rome: Ediesse, 2014), 82. Carla Lonzi herself has repeatedly addressed the risk of madness in her diary, as well as in her political writings, referring to the experiences of figures such as Zelda Fitzgerald, Virginia Woolf, Sylvia Plath, and Dora, as well as other women psychoanalyzed by Freud. For more on this, I refer the reader to Carla Lonzi, “Itinerario di riflessioni,” in È già politica (Milan: Scritti di Rivolta femminile, 1977), 13-50; and Carla Lonzi, “Mito della proposta culturale,” 148-149.

- For more on the experience of Lee Lozano, I refer the reader to Helen Molesworth, “Tune In, Turn On, Drop Out: The Rejection of Lee Lozano,” Art Journal, 61:4 (2002), 64-73; and Jo Applin, “Hard Work: Lee Lozano’s Dropouts,” October, no. 156 (spring 2016), 75-99.

- The very first time I heard Claire Fontaine talk about the political illegibility of Carla Lonzi’s radical practices was during a conference held at HEAD-Genève in 2017. A thought-provoking and in-depth reflection on the subject will soon be published by Claire Fontaine in the book Gervasia Bro(x/cs)on, currently being edited by artist Camille Dumond and myself for the series Entretiens pour un film, released by Editions Clinamen (Geneva, 2021).

- This awareness and the choice of self-sacrifice and self-nullification, with the suffering it generates, are reminiscent of the logic of martyrdom and/or sacrifice which, according to hagiographic chronicles, structured the life and experience of several women saints. This parallel does not seem so absurd if one considers Carla Lonzi’s interest in the figures of saints such as Teresa Martin, that is, Santa Teresa del Bambino Gesù, or Teresa d’Avila, of whom Lonzi was an avid reader since she was a child. It is no coincidence that the essay “Itinerario di riflessioni”, in which Lonzi relates to a series of figures who inspired her thinking, opens with a reference to the two Teresas. Carla Lonzi, “Itinerario di riflessioni,” 13-14. Curiously, other Italian women writers and thinkers who have deserted the ascribed sociocultural role and rejected the traditional model of femininity imposed on them have shown a certain degree of interest in the stories of the martyr saints, as is the case of Goliarda Sapienza who, in her beautiful book L’arte della gioia, relates the experience of Modesta to that of Sant’Agata.

- This is what Maria Luisa Boccia describes as “leaning on the void,” which corresponds to the lack of identity on which women’s subjectivity rests after all given roles are deserted and holding on to this lack is the only possibility left to exist. For more on this, I refer the reader to Maria Luisa Boccia, Con Carla Lonzi. La mia opera è la mia vita, 31. As Liliana Ellena has put it, the process of becoming “myself” is estranged from the “I”, understood as the need to stay put in fixed identities. For more on this, I refer the reader to Liliana Ellena, “Carla Lonzi e il neo-femminismo degli anni ‘70: disfare la cultura, disfare la politica,” in Lara Conte, Vinzia Fiorino, Vanessa Martini (eds.), Carla Lonzi, la duplice radicalità (Pisa: ETS, 2011), 134 (my translation).

- This challenge to signification and the search for a new language to name and therefore think, practice, and experience reality differently, was performed by different means throughout the course of Carla Lonzi’s life. At first, she attempted to do so through poetry, recalling Audre Lorde’s famous declaration of poetics Poetry is not a luxury (1977). At a later stage, it was made through the practice of autocoscienza (consciousness raising), which is supposed to enable those who exercise it to rename reality from experience. Lastly, it was reached through prophetic enunciation. Indeed, throughout her diary, Carla Lonzi depicts herself in the role of the prophet who does not embody the event (that is, the unpredicted subject) which is doomed to change the course of history, but prefigures and announces such an event instead. The prophet, indeed, sees in the present what is already there, but others cannot see. The prophet’s word is spoken in the desert, destined to remain unheard, illegible. Maria Luisa Boccia, Con Carla Lonzi. La mia opera è la mia vita, 73-79.