L’allégorie des Polly Pocket

Interview de Morag Keil au sujet de l'enseignement et de la pratique de l'art à distance

Résumé

À travers des vidéos, des installations immersives ou des dessins, Morag Keil envisage avec un humour désabusé l’impact de ce que Shoshana Zuboff a fameusement nommé le capitalisme de surveillance. Ce modèle économique n’a fait que se renforcer à la suite des multiples confinements et appels à pratiquer le télétravail durant la pandémie de Covid-19, rendant du même coup plus sensible la précarité de la vie dans des territoires urbains gentrifiés. Professeure invitée au Work.Master en 2020-2021, l’artiste écossaise revient sur son expérience d’enseignement à distance et sur les méthodes qu’elle a mises en place pour esquisser des formes de collectivité digitales avec ses étudiant·e·s. Ensemble iels ont créé le film Great expectations/ broken dreams qui imagine une école d’art alternative.

Texte

Sylvain Menétrey: You made install a computer to interact with your students of the Work.Master program during lockdown, while you were stuck in London. Can you describe the remote teaching apparatus you implemented?

Morag Keil: The idea was that we could get a powerful computer that all the students could remotely access so that even if their personal computers didn’t have the best capacity this would give them access to a computer with higher processing levels. This could be used for their personal work or for the group editing we were doing as part of the Labzone workshop. I also wanted to put open-source programs on to it so that all the work we did in the Labzone used open-source software, in the hope that learning this would mean that when the students are no longer at the school, they still have software that they can use and afford. There were some hurdles, with some people’s personal computers not being compatible with the remote desk-toping programs, or internet connection meaning that there was a lag when we remotely logged in, which made editing frustrating. The hope was that the students felt some ownership over the computer, and it could exist as a digital space that they have control over. I’m hoping it could be open to other students who were not in the Labzone for group projects even after the pandemic.

S.M.: What were you editing on the computer?

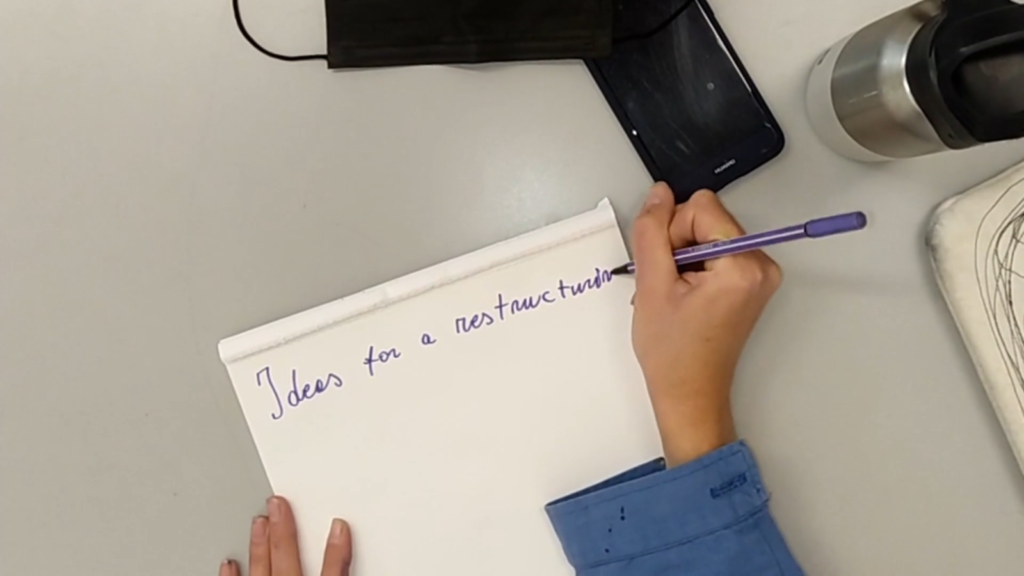

M.K.: We made a film about everyone’s experience of art school. Everyone who is on the master program has done some form of art education before, so they tell the story of their BA… it is very narrative at the beginning. And then they describe how they ended up coming to HEAD, their experience of the school and eventually their experience of the pandemic. It’s a reasonably pessimistic film, but at the end we have ideas for another art institution. We reimagine the art school experience, and there is a practical list of things the students would like. It has some cynical points, but we put so much work into it. How can it really be cynical when we spent so much time on it? [Laughs]

S.M.: How did you work collectively?

M.K.: I was thinking about how filmmaking can easily embody multiple positions or opinions but still you end up with one work in the end. I was looking at different languages of community filmmaking, where it is a lot of working out how to edit and make decisions as a group. Because Labzone was on a computer I figured we could do it remotely, but it was still difficult; there was a lot of waiting for rendering and processing. The film is finished now, it was first screened during the Grand Tour in July 2021.

S.M.: On the infrastructure level of art education, using open-source programs and equipping the students with them for their future is an interesting initiative. Did you feel it was something much needed?

M.K.: It was needed but the issue was that I was also not familiar with the programs. I was a hack myself, so we were all learning together. And I think that doing it online had too many levels of frustration. We were mostly focusing on using the video editing program DaVinci Resolve, which some of the students had used before and others not, so we collectively had frustrations with it because we were all learning. But I think it is really needed and good thing to do. Perhaps I failed in structuring it in a more accessible way that would have been more user friendly. We should have made something smaller before launching into making the film, just to learn the program. When we used HOTGLUE it was a bit more accessible and quicker. It works well as a visual editor and as a mood-board, especially with a large group.

S.M.: Was this remote teaching at HEAD – Genève your first teaching experience?

M.K: I have been teaching at a community centre in London for the past ten years. It’s a very different structure to a university, the centre is for disabled adults, and I facilitate art sessions there. The social aspect of the centre is super important and although some sessions will involve more formal teaching, for example a casting workshop or an art history session, mostly we are listening to music, chatting and making art. Participants usually have their own idea of what they want to do and I’m there to either physically help them or to help to problem solve.

If we had been able to do in-person teaching I would have liked to try to construct a space like this one in the Labzone, where students could experiment and socialise, with a loose aim of creating something collaborative at the end. The computer was about the desire to create a digital space when we didn’t have the option to have a real one.

S.M.: Your past videos, installations, exhibitions echo somehow what we collectively experienced when we were all locked in our home and tied to our computer screen. The feeling that your work exude is at the same time quietly dystopian and humorous. I have in mind passive aggressive (2016), your exhibition at Eden Eden, but also Here We Go Again (2018) at Project Native Informant. I’m interested to know how you turned this alienating experience of the pandemic into something more positive for the students.

M.K: Ha ha, yes! I didn’t use a studio for a while so I would be working from home when art making and video editing. Because of the housing situation in London, in that it is very expensive, all my bedrooms have been very small and usually there is little or no communal space. So, if you’re using your bedroom as a studio, it can get tight. This also meant that most of what I was around physically was domestic, even though I would go out to teach.

Housing has played a massive role in my life because it has been so fundamental to what is possible, like the whole A Room of One’s Own (1929) argument. To create, you only need the stability of a room, but in renting from a landlord in London a lot of that stability is taken away from you. The city became the biggest thing in my life and it still is.

With art I have felt stuck for probably about eight years now, after all the drive to become an artist, to find a structure that could allow the time to make art, and then the disappointment of the market-driven art world. I’ve been in a period of trying to work out how I would make art and for who, etc. For a while, I have felt stuck in a feedback loop, and so this stuck-ness shows in all my work, with everything boxed-in or repeating.

I have these dreams sometimes that are apparently common to other people too. I will be in the house, and everything will be normal, and then I will find this other room or a series of rooms, usually highly baroquely designed and much bigger than any of the other rooms, and I’m always left wondering, why don’t we use this space?

To answer your question, I don’t know if it is possible to make the pandemic experience not alienating. Labzone changed from a workshop that had been so much about the social and being there in person. I think the best thing we have done together was having group viewings on CyTube – a website that allows you to watch YouTube videos in sync, with a text chat at the side – and Chatroulette inspired rotating conversations on Discord, where we set up different “rooms” and people could bounce between them.

S.M.: With Hogmanay, your most recent exhibition at Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi that opened in February 2021, you radicalised the feedback loop nightmare that you’re describing to an almost grotesque way, with this cyber punk dentist chair and monitors [Chris, 2021]. Did the monitors broadcast what was happening in the gallery space?

M.K.: Actually it’s a video of my own bedroom that was intended to look like a live stream but it’s fake.

S.M.: It made me think about the movie Strange Days (1995), where people are killed while wearing a helmet on their head that is making them witness their own torture and murder from an outside perspective.

M.K.: Some things are accidents. I never thought about how the chair would look more like a torture machine than a chair, because that was not intended, but in the end if you mix electronics with a chair it is going to look like an electric chair or a dentist’s chair. Some sort of operation is now going to happen to the visitor, where it was intended to be a tool for them, but it flipped. To an extent that was not on purpose.

S.M.: Yes, although it could be both: a chair on which you can be tortured and a chair that gives you almighty control from this “workstation”, as you have called it. I think that the Polly Pocket posters that feature in the same installation are kind of ironic in relation to what you have said about the tiny spaces for creation that you have available to you. There is a sense of the mise-en-abîme, a miniature world that is controlled and controllable.

M.K.: Yes. It is unclear if you are the puppet or the puppet master. The thing about art making is that some things happen by chance. My friend has an empty studio flat in Elephant and Castle, and I was able to go and stay there. Because I live with quite a lot of people, it gave me the chance to have a break from living with them during the pandemic. There was a Polly Pocket there and I love them. Then I started making loads of time lapses. It’s hard to say why things happen, because I had been making time lapses in my house as well of the clock in my kitchen. Time lapse is so much about time passing. It takes a long time to make it and a long time to edit it, but it condenses time. I thought it was funny to make this during lock down, where time passing has become abstracted. In my experience, most of the days were the same. So, I made a time lapse of the Polly Pocket zooming out from that tiny world into the tiny world of the studio apartment. It works as a feedback loop again: the Polly Pocket fictional candy world that is controlled, and the real “Polly Pocket” which is the studio apartment itself. The printed posters in the exhibition are frames from the time lapse.

But there is an element of chance. If there hadn’t been a Polly Pocket in the studio apartment, I would not have made that work.

S.M.: Serendipity.

M.K.: Yes. Although the chair was premeditated. That started because my flatmate makes cosplay stuff, and I wanted to go deep into the cartoon world of cosplay, cyber-punk dystopia that has such a set language. It is based on the chairs from the video game Fallout 4 (2015). My flatmate was supposed to help me but he got too busy, so I ended up making it myself. It was cool to be spun into a world where I was slightly less comfortable with what I was working with.

S.M.: Did you find the chair second hand?

M.K.: It’s a cinema seat that already had some electronics in it that would have enabled it to recline and light up.

S.M.: I mentioned the grotesque feeling that I had seeing this exhibition. I was wondering how much the pandemic has influenced you, in the sense that what you had been forecasting through the work arrived. There is a new kind of humour. It is less depressing and there is this escape through fiction.

M.K.: I was not directly addressing the pandemic. It became a ridiculous thing to do because I was having to make this chair. Usually, I would do so by going to markets, but the markets were all shut. I would be in a temporary studio wondering why I was doing it, because it felt over the top when the conditions were so challenging. It felt inconsiderate to the fact that there was a pandemic, even to be making an art exhibition. Though perhaps there is something in what you said, I let go a bit and stopped worrying about meaning, stopped worrying about interpretation, went more with instinct. I constantly suppressed the question why.

The film of the New Year’s Eve party, Hogmanay (2021), was an idea from before. It was about making a time signature, again about the passage of time and the fact that New Year’s is such a symbolic passage of time. I had been given a year to make the exhibition, which was before the pandemic, and which ended up being extended. I didn’t allow the pandemic to stop me showing it, even though afterwards it felt like a weird thing to do, given that parties were not permitted, and it would be seen through that lens. I did wonder if it was my job to make a cultural product that was a response to the situation, but I couldn’t, so I didn’t.

I hadn’t made a film in such a structured way before Hogmanay. I made it with my flatmates so I had to be better organised and tell them what to do. It’s kind of scripted.

S.M.: You said that the housing situation in London has had a great – good or bad – impact on your work. I was wondering what makes you stay in London though.

M.K.: I now live in a housing co-op, so we all own the property, and it is managed by us. It is a more utopian situation, being without a private landlord. I had been focused on changing that to get a bit more stability and to not be at the whims of these landlords.

I have been here twelve years and I have my life and my friends and my job here, so it’s not so much that it’s interesting but it’s where I built my life. I came to study in the capital. Growing up in the UK as a young person, you are told it is the cultural capital, even if that’s not true. But you get stuck in big cities.

S.M.: The time and its value is something I would like to finish with, because you have mentioned it several time and it is also a notion that comes back again and again in your work. You made for instance this work called Clock (2018) that is a clockface out of different shoes. Is the passing, but also the repetition of time, something that makes you anxious?

M.K.: I guess it’s that time is dynamic – it moves. I got really into making art that was more like an experience or a theme park. If you make kinetic art, it’s going to be more dynamic. But it’s the same with a film. It moves in time. It’s repressive, it’s repetitive, but I also like that it gives a beat. It’s a constant, but it can be psychedelic as well. Time can slow down. With painting I am always frustrated because when you finish it, it stops, although it ages like a person. But if you make something mechanical it will show you that it changes because it keeps moving. The interest in the shoes was that they move, they walk. It came from a display I’d seen in a charity shop where a shoe had been placed on top of a pile of books. I went from there to the shoes being the numbers on the clock. They are in a circle, moving forwards but always back around. Everything is also stuck in my own logic. Perhaps it is a narrative of frustration about the limitations of what I can make. It also looks funny. It’s a goofy thing.