Texte

In 2020, the Mexican artist Julieta Gil realized a digital work called Nuestra Victoria, (“our victory”). It consists of a computer model and prints that reproduce Mexico City’s Angel de la Independencia in the various “vandalized” forms that it took on during the protests of the summer of 2019. That massive wave of protests against systemic violence against women in Mexico saw the Angel de la Independencia covered over and over again by feminist and anarchist graffiti. Within days, these tags were removed by government cleaning operations. In this way the patriarchal government of Mexico physically erased the protestors’ expressions of outrage and discontentment and at the same time tried to discredit the demands of the feminist movement.

In preserving the multiple forms of the “vandalized” monument, which was erected in 1910 to celebrate Mexican independence and thus glorifies the settler-colonial nation-state, Julieta Gil directly tackles the way in which vandalism of monuments is generally perceived: a perturbative unsettling of “pacified” public space, from which debate and social conflict have been made to disappear. However, these modifications of the appearance of the monument carried out by activists can also be seen as a harmless expression of civil society regarding its history, the politics of its remembrance, and its representation in the official narratives of history. A chronological tracking and documentation of these alterations of the monuments can actually help to construct another understanding of what is at stake in the social struggles that appear, against official wishes, in public squares and spaces.

The reflections offered here are based on research into the long history of “vandalism” of Geneva’s International Monument of the Reformation (also known as the “Mur des réformateurs” or “Reformers’ Wall”). Built between 1909 and 1917, this tribute to the Swiss Protestant Reformation includes separate statues of four main protagonists of the reformation: Guillaume Farel, Jean Calvin, Théodore de Bèze and John Knox. The Reformers Wall has been the site of many expressions of social conflict. In my research, I repeatedly came across references to the “Genevian tradition” of “vandalizing” this monument; the marking of the Reformers’ Wall seems to be a bellweather of the Genevan, Swiss and even international political climates.

Of course, my account here is not exhaustive: it does not pretend to document all the protests that have made the monument into their visual support. Municipal archives do not necessarily record acts of vandalism, especially those considered to be minor. I imagine however, that this partial archive at least indicates some interesting moments in a local history of social tensions that also reflect the changes in global political temperature.

The first intervention on the monument seems to date back to 1933. I have found mention of “large red letters” attributed to the Socialist Party, in a time of rising fascist and far-right populist forces across Europe – specifically, in that year, the rise to power of the Nazi Party in Germany.

Between 1960 and 1970 alone, the Reformer’s Wall saw at least nine alterations, mostly accomplished with red paint. It is estimated that the renovations and cleaning operations from these ten years alone have led to a surface loss of 2.5cm.1 Ironically, the imperative to preserve the monument in its “civilized” form or condition have actually contributed to its degradation.

In 1975 and 1976, the monument got other paint jobs. The 1975 operation is documented in the black and white photograph included here.

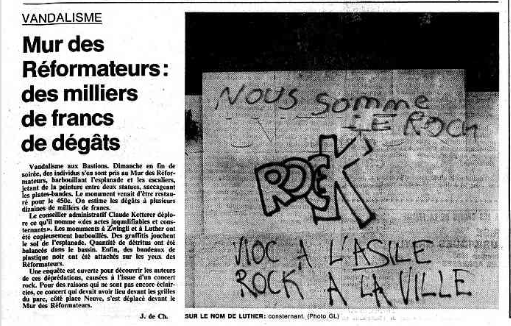

Important renovation work was carried out between 1985 and 1987, including the replacement of the heads of Théodore de Bèze and Jean Calvin. In the meantime, the monument appeared to have been tagged during a concert at Parc des Bastions in 1986, with the words “ROCK, Rock à la ville, viocs à l’asile” (“ROCK, Rock in the streets, boomers in the bedsheets”).

On May Day of 2009, red paint was splashed on Calvin’s head alone. It seems that this is a Labour Day tradition in Geneva.

In 2014, a man acting on religious motives according to the Tribune de Genève (a follower of the antichrist, to be more specific) attempted to carve a message with a hammer and a chisel on the bottom of the monuments but was prevented from doing so by the crowd that was present in the park.

Finally, the year 2019, which saw massive protests in Mexico and repeated graffiti on the Angel de la Independencia, also saw its share of civil expression on the Reformers’ Wall in Geneva. On 4 March, a tag reads “Où sont les femmes?” (“Where are the women ?) leading up to International Women’s Day, followed by “Où sont les queers?” (“Where are the queers?”) painted ten days later. That same year, on the night of 14 July, paint was thrown over the monument, reproducing the patern of a rainbow flag.

In 2007, Jacques Rancière published Hatred of Democracy2, analyzing how a certain silencing of democratic debate now operates at the very core of the so-called democratic order of western nation-states. It is extremely compelling to read Rancière’s Hatred of Democracy while thinking about iconoclasm and monumentality. Rancière explains how maintaining the appearance of civility in public space is central to an actual contempt for democracy: vigorous public debate about social conflicts and differences is supressed in the name of good manners. Under this sign of civility, democracy is restricted and undermined not by totalitarianism, autocracy or dictatorship, but under the functioning of an order that claims to be democratic. Rancière describes the double discourse of the hatred of democracy, which encompasses the rejection of both affirmative action and public debate exceeding the limits imposed by the state, as well as the use of the military to enforce law and order. We have seen exactly this in France with the yellow vests protests. When the mythical pacification and civility of public space is broken open, real social stakes and true faces show themselves.

Targetting the visual appearance of the monument directly tackles the fiction or projection of a unified people behind the symbols and protagonists of what is claimed to be its culture – regardless of the racist, colonial, queer-phobic or mysoginistic values that such symbols may actually represent. The truth that is revealed by the degradation or defacing of the monument, whether the Angel de la Independencia or the Mur des Réformateurs, is that a certain persistant awareness and rejection of what these symbols actually represent in terms of power relations now animates the public debate – and can be perceived as an index of political activity that goes beyond the bounds of “civility” set by nation-state governance.

This depiction of the political and ideological forces that disrupt the democratic process in the modern era is for me also relevant to Wendy Brown’s account of “apocalyptic populism.”3 In eurozine in 2017, Brown described the way neoliberal influence on democracy results in the privatization and depletion of public services, and decreasing satisfaction of basic needs such as education, health care, work and housing. This is due, she argues, to the shift between the two divergent imperatives that drive (social) democratic, and neoliberal policy: democracy treats common law as a priority, a guide for its stabilization, while, under the laws of neoliberalism, individual freedom prevails. What she describes as the takeover of democratic governementality by liberal forces facilitated by the imperative of economic interest under capitalism, culminates in the recent association of hyper liberalism with right/far-right populism, as seen in the governments of Trump, Bolsonaro, Macron or Johnson, which fan the embers of a desire for destruction and restoration of a fantasized conception of law and order close to the heart of alt-right populists. This picture helps to illuminate how, in the current social, economic, ideological, migratory, political and climate crisis, a politics aiming at the emancipation of marginalized and excluded groups, feminism, antiracism, and queer struggles are being depicted by reactionary forces as regressive and oppressive movements that would be the true dangers of the socio-economic stability of our societies. (The circulation of terms such as “feminazi,” “khmers-verts” or “islamogauchiste” in the media are examples of the language at work there.)

The hatred of democracy is certainly not a novelty. It is as old as democracy for a simple reason: the word it self is an expression a hatred. It was first an insult invented, in ancient Greece, by those who saw the ruin of all legitimate order in the unspeakable government of the multitude.

Jacques Rancière, Hatred of Democracy. 2007.

Rancière’s words capture the rejection of government by the multitude at the very time and place where, it is claimed, democracy was born, (on a basis of mysoginistic, classist, xenophobic and ageist power dynamics) and the automatic association of a governing multitude with a state of chaos and the ruin of civility. A very similar conception is at work in official and media portrayals of anarchy. What Rancière highlights here is that the rejection of the popular right to self-governance – precisely under the pretense of a concern to protect and preserve common law – has a long history in so-called democratic order.

That “anarchist” grafitti is denounced by dominant forces and used as a means to attack the legitimacy of social struggle and affirmative action that takes place during demonstrations in public space, is for me more indicative of what is played out in parliaments and national assemblies than in the protests themselves. Reading Rancière and Brown help to see how an unquestioned notion of civility and democracy can be mobilized to restrict the appearance of real democracy and possibilities for opposing and questioning the symbols and structures of power. Democracy does not consist in maintaining the symbols of law and order in a pristine condition. As long as self-management, feminism, anti-racism, queer struggles or ecology remain delayed agendas in the so-called democratic order, it will be legitimate to paint and target the monuments.

Notes

- The information about the 2.5 cm surface loss is mentionned in an article in Le Temps, 8 July 1965. « In order to clean the Reformers’ Wall from the layer of red dye that vandals had poured on it during the night of April 22-23, the scraping system, whose repeated use had already resulted in the removal of 2.5 centimeters of stone, was abandoned this time. »

- Jacques Rancière. Hatred of Democracy. Verso. 2007.

- Wendy Brown. « Apocalyptic Populism, » Eurozine, 2017.

Retour au sommaire

Retour au sommaire