Résumé

Diplômée en 2014 du CCC, l’artiste et activiste Marisa Cornejo a réalisé un film qui revient sur les événements de Plaza Italia à Santiago, renommée Plaza de la Dignidad depuis le 18 octobre 2019. Pendant plusieurs semaines, des manifestant·e·s s’y sont rassemblés face à la répression policière pour réclamer une meilleure justice sociale et l’abrogation de la Constitution héritée du régime d’Augusto Pinochet. La statue du général Baquedano qui trônait au centre de la place a été retirée par le gouvernement le 13 mars 2021 après les déprédations intervenues sur ce symbole des divisions chiliennes. Héros militaire pour certain·e·s, génocidaire de populations indigènes pour d’autres, Baquedano s’en est allé au milieu de la nuit, par la petite porte. Cornejo s’est associée à sa fille Katya Kasterine et à Cecilia Moya Rivera (étudiante du CCC) pour adosser le film à un essai à plusieurs voix, un journal de bord de la contestation – publié en anglais et en espagnol. Ensemble elles retissent la mémoire d’un pays traversé par de multiples conflits, espérances, violences et inégalités, dont la présence absente de la statue du général devient le leitmotiv. Cet article est un nouvel épisode et la coda du focus publié l’an dernier: All Monuments Must Fall.

Texte

A quick overview of what happened

On Friday, 18th of October, 2019, a series of mass protests inaugurated the largest social revolt in Chile since the end of Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship (1973-1990). This day is remembered as the beginning of the so-called estallido social, during which millions of citizens took to the streets to demand a decolonial commonwealth. The people wanted an end to the neoliberal model – first imported to Chile under the Pinochet regime with the advice of U.S. economist Milton Friedman – and an end to centuries of colonialism by the hegemonic powers of Western Europe and the United States of America. Along with the protests, a slogan was born that perfectly described the people’s demands: ‘hasta que la dignidad se haga costumbre’ (‘until dignity becomes a habit’).

Since then, the government of the moment, presided over by right-wing billionaire Sebastián Piñera, has responded by violating human rights and refusing to implement structural changes. Meanwhile, the population created murals, performances and collective actions, turning public space into an experimental open-air museum1.

There have been human rights violations since the beginning of the revolt: 343 people were victims of eye trauma according to government figures, and 3,838 people have suffered injuries caused by state agents.

The following people lost their lives:

Cristián Valdebenito

José Matamala

Irma Gutiérrez

Ariel Moreno

Sergio Bustos

Jorge Mora

Mauricio Fredes

Abel Acuña

Robinson Gómez

Héctor Martínez

Maicol Yagual

Agustín Coro

Joel Triviño

Cardenio Prado

Mariana Díaz

Alex Núñez

José Uribe

Manuel Rebolledo

José Arancibia

Eduardo Caro del Pino

Kevin Gómez

Romario Veloz

Manuel Muga

Andrés Ponce

Yoshua Osorio

Julián Pérez

Luis Salas

Renzo Barboza

Paula Lorca

Alicia Cofré

Mateusz Maj

Words around the square

Katya

In June 2020, in Bristol, where I live and study, Black Lives Matter protesters took down a statue of slave-trader Edward Colston and threw it into the harbour, sparking a series of similar events around the world. Almost a year later, in my motherland, Chilean officials took down the statue of General Manuel Baquedano in Plaza de la Dignidad (Dignity Square). Although the statue symbolises the country’s colonial past, during the estallido social, Chileans reclaimed it and transformed it into an empowering tool to express their discontent. Since October 2019, young protesters have fearlessly climbed on the horse and chanted ‘Chile Desperto!’ (‘Chile has awoken!’). They have decorated it with the Mapuche flag, anti-government slogans such as ‘No + AFP’ (‘No more Pinochet-era pension system’) and expressions of resistance ‘Wallmapu Libre!’ (‘Free Wallmapu!’).

In December 2019, I flew from Bristol to Chile to spend the holidays with my family. My mother picked me up at the airport and I looked out of the window the whole way home. Santiago was unrecognisable. Despite my Chilean heritage, I felt like an outsider as I rediscovered the city as a battlefield of the estallido social. From one day to the next, I went from the dark, cold winters of Europe to the desert climate of Santiago, where tensions between protesters and military forces were increasingly high. I was astonished and inspired by the passion and dedication of Chilean activists.

My mother and her friends took my brother and me to Plaza de la Dignidad on New Year’s Eve. I could feel the tear gas in my eyes from blocks away. My mother reminded me that I had to be cautious, but all I could pay attention to was the people climbing and dancing around the statue. I felt joy and pride as I watched Chileans celebrating the New Year and their battle for dignity.

Today, the square is empty of protesters and full of military forces, as we can see in the images of ‘No Monument.’ Despite these discouraging images, the man being interviewed in this short documentary video expresses his anger in a powerful speech. One of the Chilean protesters left in Plaza de la Dignidad, he mocks and denounces the authority’s cruelty and cowardice. ‘No Monument’ is a useful tool to initiate discussions about activism, police violence, and the significance of statues and urban spaces in social movements. I was eager to help my mother translate the subtitles into English. Although Spanish is my mother tongue, I sometimes struggled to keep up with the quick pace at which Chileans speak. It was also challenging to figure out what the interviewee was saying against the background noise. I hope that I appropriately translated the interviewee’s message.

Marisa

I.

Fui a Chile en diciembre de 2019, días después de conocer a Cecilia en Ginebra. Llegué después de meses de seguir el estallido social desde las redes sociales de manera obsesiva y en estado de shock. Veía simultáneamente manifestaciones llenas de alegría y esperanza junto al mismo terrorismo de estado que mi padre Eugenio Cornejo había sufrido y denunciado. Después del golpe de Estado de 1973, mi padre fue detenido y torturado. Ese terrorismo de estado estaba presente en 2019, y habíamos jurado luchar para que nunca más nadie lo sufriera. Al estar allá comprendí que necesitaba organizarme para ir con amigxs a la plaza de la Dignidad y así permitirles a mis hijos conocer ese espacio y realidad candente, a todos los niveles. Entonces decidí organizar visitas con mis hijos en días que no fuese viernes2. La primera vez que estuvimos ahí, fue en medio de una tarde súper calurosa de diciembre. Fue como entrar a un territorio de guerra, no había baldosas en las veredas, habían sido convertidas en pequeñas piezas de piedra en el piso que daban la dimensión de lo que había ocurrido ahí. Todo estaba pintado, todo transformado por manos humanas, tratando de defenderse sin armas.

El 31 de diciembre de 2019 volví al lugar con dos amigos: Macarena Aguiló y Arnaldo Rodriguez[note]Quienes me hablaron de los riesgos que corrían fotógrafos y videastas registrando los eventos.[/note] – ambos amigos ligados a mi exilio –, y con mis dos hijos más jóvenes. Esta vez celebramos y nos fuimos encontrando con amigos por todas partes, ¡hasta nos encontramos con Carmen Castillo a unos metros del monumento Baquedano! El lugar estaba lleno de gente celebrando con bandas de música, canto y baile, que sobrevivía a las oleadas de gas lacrimógeno que iban pasando. Por casualidad nos encontramos también con mi primo Joaquín Figueroa, que estaba descansando cerca del monumento después de haber estado en la primera línea y que invitó a mi hijo Tom a tirar cuetes3 junto con otrxs niñxs4. En este segundo encuentro con plaza dignidad, mis hijos me pidieron permiso para ir a celebrar y yo muerta de miedo, finalmente los dejé perderse en la multitud con otrxs amigxs de su edad mientras yo me me quedé ahí junto a Carmen Castillo, mudas, fumando, mirando ese momento histórico.

Luego de media hora de lacrimógenas, celebraciones y cuetes nos reencontramos todxs, nos dimos cita al lado de un hospital de emergencia organizado por voluntarios y volvimos todxs sanos y salvos a casa. Ese sería el cierre del año y de una era. Somos sobrevivientes.

II.

Más de un año después pasé por Santiago en plena pandemia. Todo el mundo me decía que no había que ir a poner el cuerpo a la violencia del Estado en la Plaza de la Dignidad. Que ya se había ganado la batalla política: poder cambiar la constitución de 1980 impuesta y diseñada en la dictadura para implementar el proyecto neoliberal y neocolonial que convirtió a Chile en un laboratorio de extraccionismo capitalista “ejemplar”. Siguiendo mis instintos de documentar y participar solidariamente en las luchas que buscan sanar mis heridas, fui el viernes 13 de marzo del 2021 a la Plaza de la Dignidad, a pesar de las voces que me decían que era el lumpen proletariado él único que iba a protestar. Aquí en Europa y como migrante nunca se me ha ocurrido clasificar a la gente que va a una protesta por su origen social. Lo que me hace participar es la causa. Cómo chilena que nunca ha podido volver a Chile tras el exilio tengo tendencia a turistear en todos los ámbitos sin tenerle miedo al prejuicio social. Al contrario, las expresiones populares fueron siempre fuente de inspiración para mi padre Eugenio Cornejo, profesor de artes plásticas, que me educó en ese espíritu.

Por lo tanto cuando supe que habían quitado el monumento Baquedano en la madrugada, de la misma manera en que extrajeron nuestros recursos naturales y nuestros seres queridos en la noche, para desaparecerlos, quise ir a documentar con mi cuerpo este momento histórico. Me coordiné con mi primo Joaquin Figueroa y partimos vestidos como para la guerra. Cascos y protección para los ojos. Sin él no habría podido hacer nada. Su experiencia en la primera fila durante meses lo convirtió en el mejor guía. Debo de confesar que todo el tiempo estaba rígida de miedo. Mi cuerpo no podía casi moverse, solo pegada a Joaquin pude circular. Él conocía la mecánica de la protesta y la lógica de la represión. ¿A quienes iban a tomar presos mientras estábamos a metros de la policía? A nosotros no, éramos demasiado viejos y blancos, me dijo. Se llevarían a jóvenes de 18 años, morenos y pobres. Él lo sabía, lo vimos con nuestros propios ojos, la lógica del sistema represor es maquinal y sabe calcular costos y beneficios. Filmé y fotografié con mi teléfono celular y cámara lo que pude, simplemente estar viva ahí entre tanta máquina represora era un milagro.

Volví a Ginebra, y como siempre me sucede con esos archivos con los que vuelvo aquí se vuelven nudos que irremediablemente se conectan a viejos traumas irresueltos y no sé qué hacer con tanto enredo. Acudí a mi cómplice Stéphane Fretz, que siempre ha tenido la paciencia para ayudarme a desenredar materiales. Le pasé todo lo que traje de ese día, lo miró con su espíritu crítico y amoroso y propuso un montaje. Por sobre todo decidí rescatar las voces de aquellos que seguían en la Plaza de la Dignidad después de haber ganado la batalla política y después de que el monumento había sido retirado. Las voces de aquellos que insistían en no abandonar el campo de batalla, pues no les quedaba otra razón para vivir, aquellos que hablan, hablan por mí, por los hijos del exilio que no hemos recibido aún ninguna prueba de que las reparaciones que se nos prometieron llegarán. Ellos hablan por mi, por mi falta de confianza en el mundo que tengo hasta el día de hoy que me lleva a aferrarme a los restos de mi archivo del exilio, como única prueba de mi derecho a la paz y la dignidad. Ellos protegen el aura del monumento ausente como yo protejo el aura de mi archivo del exilio, que me dice que mi padre si existió, que valió la pena luchar y ser solidario y que las voces de los olvidados de la historia no dejan de renacer en cualquier intento de justicia social. A ellos dedico este trabajo, sus voces anónimas, son las voces que yo creo Walter Benjamin habría apreciado escuchar, aquellas que nos recuerdan que el mesías, Salvador Allende y las grandes alamedas siempre se abrirán mientras no olvidemos luchar por la justicia y la memoria.

Marisa

I.

I travelled to Chile in December 2019, a few days after meeting Cecilia. I arrived after months of obsessively following the social outburst via social media, in a state of shock. I watched these demonstrations, full of joy and hope, taking place alongside the same state terrorism of which my father Eugenio Cornejo was a victim. Following the coup d’état in 1973, my father was detained and tortured. Although we had sworn that nobody would endure such suffering again, it was present in 2019. Being there, I understood that I needed to arrange to go with my friends to the Plaza de la Dignidad on days other than Fridays to allow my children to know that space and burning reality, at all levels5. The first time we were there, it was the middle of a hot December afternoon. It felt like entering a warzone. The tiles on the pavements had been transformed into small pieces of stone, indicating what had happened there. Everything was painted; everything was transformed by human hands trying to defend themselves without weapons.

On 31st December, 2021, I returned to the square with two friends: Macarena Aguiló and Arnaldo Rodriguez6 – whom I met during my exile – and with my two youngest children. This time we celebrated; everywhere we met friends. We even met Carmen Castillo a few metres from the Baquedano monument. The statue was completely covered with people celebrating with music bands, singing and dancing, surviving the waves of tear gas that were passing by. By chance we also met my cousin Joaquín Figueroa, who was resting near the monument after having been in the front line7. Joaquín invited my son Tom to throw cuetes together with other children. In this second encounter with Plaza de la Dignidad, my children asked me for permission to join the celebration and I, scared to death, finally let them get lost in the crowd with other friends of their age. Meanwhile, I was mute as I stood next to Carmen Castillo and watched such a transcendental moment.

After hours of tear gas, celebrations and cuetes we all met up again, gathering next to an emergency hospital organised by volunteers. We all returned home safe and sound. That would be the closing of both the year and an era. We are survivors.

II.

More than a year later, I passed through Santiago in the middle of the pandemic. Everybody was telling me it wasn’t a good idea to go and expose a defenceless body (poner el cuerpo)8 to the violence of the State in the Plaza de la Dignidad. I was told we had already won the political battle. We were able to change the constitution of 1980, imposed and designed in the dictatorship to implement the neoliberal and neo-colonial plan which had transformed Chile into an ‘exemplary’ project of capitalist extractionism. On Friday, 13th of March, 2021, I went to the Plaza de la Dignidad in spite of the people telling me that only the Lumpenproletariat would be going. I decided to follow my instincts and heal my wounds by documenting and participating in the protests. Here in Europe, and as a migrant, I had never thought to classify people who go to demonstrations by their social class. What makes me participate is the cause. As a Chilean in exile, I have the tendency to be a tourist in all kinds of situations without fearing social prejudice. On the contrary, the popular vernacular practices (arte popular)9 were always a source of inspiration for my father, Eugenio Cornejo, an art teacher, who educated me with his spirit.

As I discovered that the Baquedano monument had been removed, in the same way that they had extracted our natural resources and captured our loved ones in the night to disappear them, I felt impelled to go and document this historical act with my body. I coordinated with my cousin Joaquin Figueroa and we set off dressed as if for war. Helmets and eye protection. His months of experience in the front line had trained him as the best guide; without him I couldn’t have done anything. I must confess I was rigid with fear. My body could barely move unless I was holding on to Joaquin. He knew the mechanics of protest and the logic of repression. Who would they take prisoner when we were just a few metres from police officers? Not us – we were too old and white, he told me. They would take 18-year-olds, the brown and the poor. He knew it, and we saw it in front of our eyes; the logic of the repressive system is machine-based. It knows how to calculate costs and benefits. I filmed and photographed what I could with my mobile phone and camera. The very fact of being there among so many repressive machines was a miracle.

I came back to Geneva with bundles of archives that inevitably connect to old unresolved traumas. I didn’t know what to do with so much entanglement. I went to my accomplice Stéphane Fretz, who has always had the patience to help me untangle materials. I gave him everything I had brought back and he had a look at it with his critical and loving spirit and proposed a montage. Overall, I decided to rescue the voices of those who were still in the Plaza de la Dignidad, having won the political battle and prompted the removal of the monument. The voices of those who refused to abandon the battlefield because they had no other reason to live. Those who talk in the video talk for me; for the children of the exiled that have not yet received any proof that the reparations we were promised will come. They talk for me, for the lack of trust in the world that I have to this day. This lack of trust makes me cling to the remnants of my archive of exile, as the only proof of my right to dignity and peace. They protect the aura of the absent monument as I protect the aura of my archive, that tells me that my father existed, that it was worth fighting and practising solidarity with others and that the voices of the forgotten ones of history will never stop being reborn in any attempt at social justice. To them I dedicate this work. Their anonymous voices are the voices I think Walter Benjamin would have loved to listen to, those that remind us, as the messiah Salvador Allende does, that the big Alamedas will always open as long as we don’t forget to fight for justice and memory10.

Cecilia

La primera vez que viajé a Chile luego de moverme del país, lo hice dos días después de encontrar a Marisa. Nos unía la tierra lejana del sur, la constelación Libra en nuestras cartas natales y las ganas de hablar sobre lo que pasa en Chile todo el tiempo. Luego de esa tarde de té de verbena en su taller en Ginebra viajé a Santiago y con eso a la revuelta y con eso a la Plaza Dignidad.

En aquel viaje, luego de pasar una semana en casa volví a protestar. Con Mauricio, fuimos al centro a la clásica marcha del viernes. Nos compramos una máscara antigás en la calle para poder respirar y protegernos del aire contaminado de lacrimógenas lanzadas por los pacos durante meses. Estábamos equipados como para una guerra cualquiera y en ese entonces cotidiana. Nos pusimos a recorrer la alameda, corríamos-caminábamos-corríamos verbos que dependen de la cantidad de pacos que había alrededor de la alameda y deporte obligado de cada protesta.

De repente, nos dimos cuenta que el Cine Arte Alameda se estaba quemando11. Mucho fuego y muchos pacos que no hacían nada para parar el incendio, solo se dedicaban a tiraban más y más bombas lacrimógenas para ahogarnos, mientras que les compañerxs de la calle ayudaban a parar el fuego y a sacar a la gente del lugar.

Agua sucia, gritos, gente en el piso, camillas.

Camaradas que abrían el paso para pasar el fuego.

Logramos pasar el incendio y llegar a la plaza dignidad. Ahí me encontré con mi amigo Diego que también estaba de paso en Chile, nos quedamos mirando el caballo lleno de gente arriba durante horas. Al final de la tarde me dijo: parece una escena de una serie distópica; todxs gritando y reclamando su tierra.

Luego de dos años de ese viernes, volví a Chile otra vez. A un Chile donde ya no había protestas masivas ni caballos sobre los que subirse a flamear banderas. Sin embargo, la relación romántica-histórica que tengo con el caballo me hizo volver igual a visitarlo. Así que un viernes cualquiera, sin protestas clásicas, volví a Plaza Dignidad. Está vez, el volver se transformó más bien en un intentar llegar porque solo había pacos tirando lacrimógenas y agua a un lugar vacío. Ya no había camaradas protestando ni compañerxs que ayudarán a llegar al centro de la plaza, al festival; ya no había festival ni esperanzas reunidas bajo el sol de Santiago.

Solo quedaba tierra seca y quemada y un podio vacío. Una ruina. Pero ese vacío y esa ruina no la conformaba la ausencia de la estatua que estaba arriba, la ausencia era la violencia de estado que intentaba aún dormir al pueblo.

Cecilia

The first time I travelled to Chile after moving out of the country was two days after meeting Marisa. We were bound together by the distant land in the South, the Libra constellation in our birth charts and the constant desire to talk about what was happening in Chile. After that afternoon of verbena tea in her workshop in Geneva I travelled to Santiago, and with that to the revolt, and so to the Plaza de la Dignidad.

On that journey, after spending a week at home, I went back to protest with Mauricio. We bought gas masks in the street to be able to breathe and protect ourselves from the air, which for months had been contaminated by tear gas thrown by the police. We were equipped as if for war, at that time a daily one. We started walking along the Alameda, we ran-walked-ran, verbs that describe the obligatory sport of every protest and which depended on the number of police officers around the Alameda.

Suddenly, we realised that the Cine Arte Alameda was burning12. A lot of fire and a lot of police who did nothing to stop the fire, but dedicated themselves to throwing more and more tear-gas bombs to drown us, while the people in the street helped to stop the fire and get people out.

Dirty water, screams, people on the floor, stretchers.

Comrades clearing the way to get past the fire.

We made it through the fire and reached Plaza de la Dignidad. There I met my friend Diego, who was also passing through Chile, and we stayed there for hours watching the bronze horse covered with people. At the end of the afternoon he told me: ‘It looks like a scene from a dystopian series; everyone screaming and claiming their land…’

Two years after that Friday, I returned to Chile. To a Chile where there were no more mass protests, no more horses to ride on and wave flags. However, the romantic-historical relationship I had with the horse made me go back to visit him anyway. So one Friday, without the classic protests, I returned to Plaza de la Dignidad. This time, there were only police officers throwing tear gas and water into an empty place. There were no more protesters or comrades to help to get to the centre of the square, to the festival; there was no more festival, no more hopes gathered under the Santiago sun.

There was only dry, scorched earth and an empty podium. A ruin. But that emptiness and that ruin were more than the absence of the statue above – they echoed the state violence which was still trying to put the people to sleep.

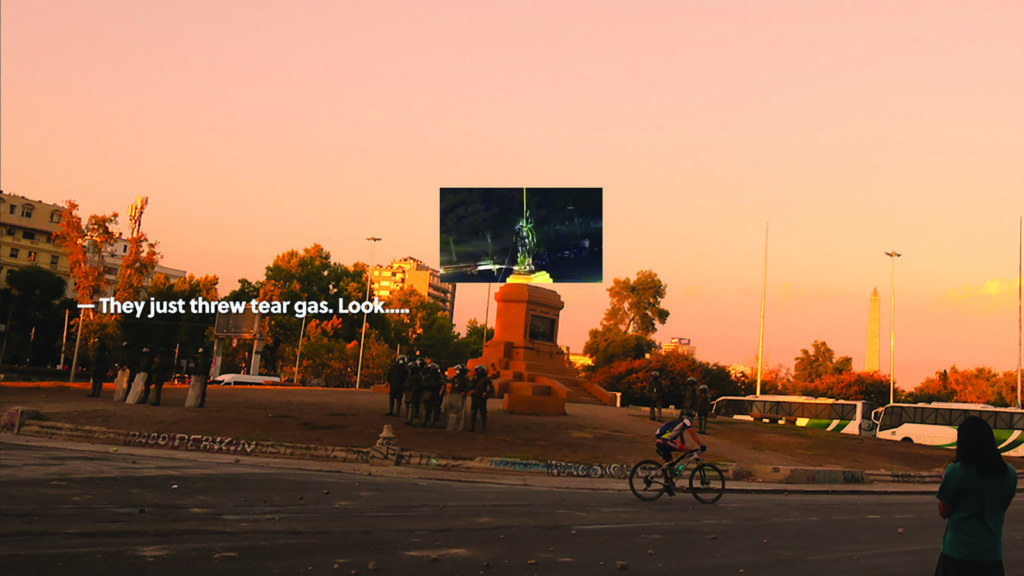

The film

The images in this film were taken a few hours after the monument of the Plaza Italia – known by protesters as the Plaza de la Dignidad – was removed and the protesters returned, as they had done every Friday since the social outbreak started, despite tear gas and police measures putting their health and vital organs at risk.

Video credits:

Size: 16:9, ultra HD

Length: 5:21

Images / sound: Marisa Cornejo

News footage: CNN, 13.03.2021

Fixer: Joaquin Figueroa

Editing: Stefan Fretz

Many thanks to: Gene Ray, Anna Papaeti, Joaquin Figueroa, Maximo Corvalán Pincheira, Mireia Sallarès, Nora Gatica Krug, Katya Kasterine, Ana Maya Kasterine, Miguel D. Norambuena

Notes

- https://artishockrevista.com/2020/02/22/convocatoria-a-ponencias-arte-y-politica-en-el-contexto-del-estallido-social-en-chile/#search

- La revuelta o estallido social comenzó el viernes 18 de octubre del 2019 y luego de eso, los viernes se convirtieron en los días de protesta masiva.

- En Chile cohete, petardo.

- La primera línea fue el lugar donde lxs jóvenes más valientes, hicieron una barrera humana para detener el avance de las fuerzas policiales que querían ocupar la Plaza de la Dignidad.

- The revolt or estallido social started on Friday, 18th of October, 2019, and after that Fridays became days of massive protest.

- Who told me about the risks taken by photographers and videographers recording the events.

- The front line was the place where brave young people made a human barrier to stop the advance of the police forces who wanted to occupy the Plaza de la Dignidad.

- ‘poner el cuerpo’ was the expression my girlfriends used to express the idea that we were offering our defencelesses bodies to police brutality. See ‘Poner el cuerpo. Formas del activismo artístico en América Latina’ 2009 (https://radio.museoreinasofia.es/poner-cuerpo)

- Jordi Ballesta and Eliane de Larminat, ‘Manières de faire vernaculaires. Une introduction’ Interfaces [online], 44 | 2020, published on December 15th, 2020, visited December 21st, 2020. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/interfaces/1453; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/interfaces.1453

- In his last discourse Salvador Allende described the Grandes Alamedas, the name of one of the avenues that leads to Plaza de la Dignidad from La Moneda, the palace of the government, as an avenue that will open where a new humanity could build a better society.

- El 27 de diciembre de 2019, el Cine Arte Alameda se quemó en medio de una tarde de protesta. Se presume que una bomba lacrimógena causó el incendio. La policía también mató a Mauricio Fredes en el mismo contexto del fuego. https://radio.uchile.cl/2020/06/03/roser-fort-por-incendio-del-centro-arte-alameda-bomberos-senala-que-podria-ser-una-lacrimogena/

- On 27th December, 2019, the Cine Arte Alameda burned down in the middle of an afternoon of protest. A tear gas bomb is presumed to have caused the fire. The police also killed Mauricio Fredes in the same context. https://radio.uchile.cl/2020/06/03/roser-fort-por-incendio-del-centro-arte-alameda-bomberos-senala-que-podria-ser-una-lacrimogena/