Domingos de llanto y jueves vacíos o Teary Sundays and empty Thursdays

By Cecilia Moya Rivera

Text

Los domingos siempre han sido difíciles. Las mañanas después de las fiestas, las tardes antes del día lunes, las noches antes de ir al colegio, noches de miedos cotidianos e inherentes. Los domingos siempre han sido difíciles y ahora aún más, porque me despierto con la nostalgia en la guata1. Los llantos de domingo en la mañana se han vuelto cotidianos. Café, tranquilidad, distancia, dolor en la espina dorsal. Bajo y subo mi dedo en la pantalla mientras veo fotos del sur de donde vengo. Gente en la calle, reclamando y yo acá, en mi pieza con el sol en la ventana y sin ruido. Acá nadie entiende lo que significa el ruido. Las máquinas en las calles, las madres gritando en las mañanas, los hombres levantando la voz borrachos y niñes llorando en las esquinas. Ruido es pobreza. Acá hay silencio y el silencio es estatus quo y a veces riqueza. Silencio es calma y abundancia.

Sundays have always been difficult. The mornings after the parties, the afternoons before Monday, the nights before going to school, nights of common and intrinsic fears. Sundays have always been difficult and now they are even more so, because I wake up with la nostalgia en la guata2. Sunday morning cries have become a regular routine. Coffee, calm, distance, pain in the spine. I scroll my finger down and up on the screen while I see pictures from the South, where I come from. People in the street, claiming y yo acá, me in my room with the sun in the window and no noise. Nobody here understands what noise means. Machines in the streets, mothers screaming in the morning, men raising their drunken voices and children wailing on the corners. Noise is poverty. Here, there is silence and silence is the status quo and sometimes wealth. Silence is calm and abundance.

Mis nuevas rutinas de domingo contienen canciones viejas de izquierda, las canto, las tarareo, les explico a mis cercanos acá lo que pasa allá. Me preguntan por qué a veces tengo tanta rabia o parezco lejos. Y es porque a veces lo estoy, siempre lo estoy, siempre estoy dislocada. Nunca lograre construir una casa con cimientos sólidos. Intento explicarles por qué es importante para mi comer palta o porque me dan miedo los pacos3 en la calle. Les muestro las protestas de allá, lejos. Les cuento porque la araucaria4 es el árbol mas lindo del mundo para mi, les muestro el anillo que me dio una de mis gemelas en Chile, les cuento que el bronce y mi pewén me protegen. Les cuento secretos de la tierra que me han ensenado otres allá, lejos.

My new Sunday routines contain old leftist songs, I sing them, I hum them, I explain to the ones I’m close to here what is going on over there. They ask me why I sometimes have so much anger or why I sometimes seem far away. And it’s because I am far away, siempre estoy lejos o no aquí, I’m always dislocated. I will never manage to build a house with a solid foundation. I try to explain to them why it is important for me to eat avocado or why I am afraid of the pacos5 – cops – in the street. I show them the protests over there, far away. I tell them why the araucaria6 is the most beautiful tree in the world for me, I show them the ring that one of my sisters gave me in Chile, I tell them that the bronze and my pewen protect me. I tell them secrets of the earth that others have taught me far away.

Los jueves siempre han sido días de luchas. Desde que soy chica7 los jueves han sido días de salir a la calle. Recuerdo las mañanas agitadas de día jueves, nos juntábamos a las 9. A.m. fuera del metro Universidad Católica, un poco antes de Baquedano –hoy Plaza Dignidad– para llegar juntes al punto de partida. Al llegar a la plaza veíamos el caballo, el caballo lleno de gente alrededor, gente que recorre las calles de la capital intentando convencer al poder de cambiar al algo. Ese caballo ha vivido muchos jueves y muchas cosas: festejos de triunfos deportivos, abrazos de año nuevo y celebraciones de triunfos políticos, como cuando Pinochet perdió el plebiscito del 89.

Thursdays have always been days of struggle. Ever since I was a girl, Thursdays have been days to go out on the streets. I remember the exciting Thursday mornings, we would gather at 9:00 a.m. outside the Universidad Católica metro station, a little before Baquedano – today called Plaza Dignidad – to get to the starting point together. When we arrived at the square, we saw the horse, the horse crowded around with people, people who walk the streets of the capital trying to convince the powers that be to change something. That horse has lived through many Thursdays and many other things: celebrations of sporting victories, New Year’s hugs and celebrations of political triumphs, like when Pinochet lost the plebiscite in ‘89.

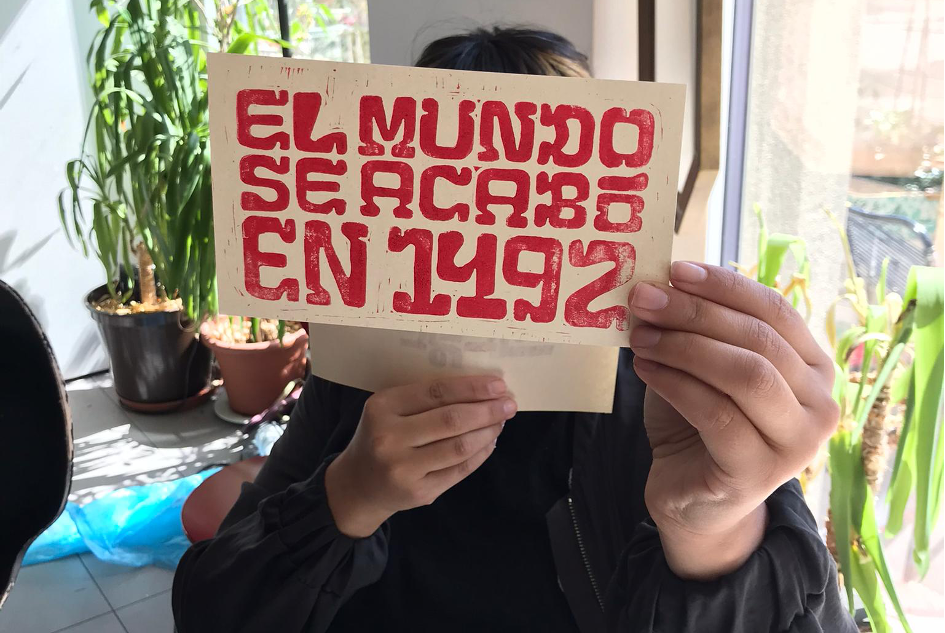

Hace un tiempo, en ese lugar de donde vengo, los jueves de marcha se convirtieron en lunes, martes, miércoles, jueves, viernes, sábados, domingos y de nuevo lunes de protestas. Todes se cansaron de la vida eterna y sin sentido. Y como el caballo seguía ahí se convirtió en el pedestal por excelencia de la lucha común: Todes alrededor diciendo que la revolución será, será ahora y será feminista o no será. Todes arriba flameando nuevas banderas. Todes arriba levantando el Wenufoye8, la bandera de luto9, la Whipala10 y tantas otras.

Some time ago, in that place where I come from, Thursday marches became Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday, Sunday and then Monday all-over-again protests. Everyone got tired of the eternal and meaningless life. And as the horse was still there it became the pedestal par excellence of the common struggle: Todes around it saying that the revolution will be, it will be now and it will be feminist or not at all. Todes arriba waving new flags. Todes arriba raising the Wenufoye11, la bandera de luto12, la Whipala13 and so many others.

Paradoxales son las banderas flameadas sobre el caballo, porque la persona que lo acompaña es Baquedano, un milico que participó en la guerra contra el pueblo mapuche, figura estrella en la ocupación del Wallmapu14 en 186815, peleando con el lonco Quilapan16 y otres caciques. Entonces el gobierno de ese Chile, que se parece bastante al gobierno del Chile de ahora, decidió homenajear su contribución al país con su estatua en el centro de la ciudad arriba del caballo.

Paradoxales are the flags flying on the horse, because the man in the saddle is Baquedano, a military officer who participated in the war against the Mapuche people, a star figure in the occupation of the Wallmapu17 in 186818, fighting with the lonco Quilapan19 y otros caciques. Then the government of that Chile, which is quite similar to the government of Chile today, decided to honor his contribution to the country with his statue, on a horse, in the center of the city.

Los domingos se han convertido en días de llanto. Tal vez siempre lo han sido y solo ahora me he dado cuenta de ello. Porque ya no hay jueves de lucha, al menos no acá. Ahora tengo domingos de llanto y jueves vacíos, ahora vivo domingos de agua y jueves de sequía, ahora me alimento de domingos acuosos y jueves secos.

Sundays have become days of crying. Perhaps they always have been and I only now have realized it. Because there are no more fighting Thursdays or at least not here. Now I have Sundays of tears and empty Thursdays, now I live Sundays of water and Thursdays of drought, now I feed on watery Sundays and dry Thursdays.

Este domingo empezó diferente, es el primer domingo de primavera y hay mucho sol, uno de los primeros de la temporada. Entra por la ventana de la esquina izquierda del salón, mientras escuchamos a Violeta20 y cocinamos juntes comida saludable. Mi hermana me escribe, es temprano allá lejos así que asumo que es importante: sacaron la estatua de la Plaza Dignidad21. Y no una estatua, la estatua, el caballo y el milico. Yo grito y todos me miran. No entienden. No entienden lo que significa que hayan quemado y sacado al caballo, lo leen, me escuchan, pero no sienten nada.22 Y la verdad, me alegro por ellos. Me encantaría nunca haberlo conocido, nunca haber conocido el significado de colonia o de lo que es nacer menos, menos desarrollada. Me encantaría nunca haber conocido el ruido, ni al desorden, ni a los pacos.

M [29.03.21 16:44]

Todo es simbólico porque desde que sacaron al caballo, llenaron de pacos y controlaron la hueá. Nos desestabilizaron.

M [29.03.21 16:48]

Hay gente que sigue yendo a Plaza Dignidad, pero no es mucha, ha bajado la convocatoria porque en realidad ya no tiene mucho sentido ocupar la hueá.

M [29.03.21 16:50]

¡Y los pacos armaron una táctica donde barren a toda la gente por la alameda23!

M [29.03.21 16:49]

Y puta estos hueones siguen haciendo las hueá que se les plante la gana y nadie los presiona (ni el gobierno ni el séquito personas en el poder)

This Sunday started differently, it’s the first Sunday of spring and it’s sunny, the first sunny Sunday of the season. The sun comes in through the window in the left corner of the living room, while we listen to Violeta24 and cook healthy food together. My sister writes me, es temprano allá lejos so I assume it’s important: they took down the statue from Plaza Dignidad25. And not a statue, the statue, the horse y el milico26. Grito and everyone looks at me. They don’t understand. They don’t understand what it means that they burned and took out the horse, they read it, they listen to me, but they don’t feel anything. And the truth is, I’m happy for them. I would love to have never known him, never known the meaning of colony or what it means to be born less, “less developed”. I would love to have never known the noise, the disorder, the cops y menos a los pacos.

M [29.03.21 16:44]

Everything is symbolic because since they took the horse out, they filled that space with pacos and they controlled la hueá. They destabilized us.

M [29.03.21 16:48]

There are people who still go to Plaza Dignidad, but not many, the number has dropped because in fact it no longer makes a lot of sense to occupy the place.

M [29.03.21 16:50]

And the cops set up a tactic where they sweep all the people through la alameda!27

M [29.03.21 16:49]

And those bastards keep doing whatever they want, and nobody pressures them (neither the government nor the entourage of people of power).

Are you ready for the commons? Are you ready to destroy and burn the present in order to create the real connection with la tierra? Are you ready for the commons for real?

– Encuentro muy interesante la noción de de Se dicen decoloniales pero no descolonizan su moral. No lo entienden, al menos no en la carne.

– Oye ¿podrías explicarme por qué todo el mundo habla de colonialismo o decolonialismo ahora? Una siempre tiene que estar dando un servicio, siempre al servicio de los blancos.

– Creo que es mejor no meter tanto ruido, hay que ser estratégicos. No usar palabras fuertes. Una siempre tiene que no hacer problemas, es mejor así. Calladita se ve más bonita.

Are you ready for the commons? Are you ready to destroy and burn the present in order to create the real connection with la tierra? Are you ready for the commons for real?

– I find the notion of decolonialism very interesting. They say they are decolonial but they do not decolonize their morals. They don’t understand it, al menos no en la carne.

– Hey could you explain to me why everyone is talking about colonialism or decolonialism now? Una siempre tiene que estar dando un servicio, siempre al servicio de los blancos.

– I think it’s better not to make so much noise, you have to be strategic. Don’t use strong words. You always have to not be a problem, it’s better that way. You look prettier when you are quiet. Calladita te ves más bonita.

Are you ready for the commons for real? Are you ready to become a real witch? Are you ready to destroy and burn the present in order to create the real connection with la tierra?

Are you ready to build the commons? Y ojo que the commons is not el concepto de common que conociste toda tu vida. Lo común es la tierra, las plantas, el choclo y las estrellas. Es lo que hay entre tu y yo, entre este espacio en que tu lees y aceptas lo que te digo.

Are you ready to become a real witch? Porque para construir lo común, tendrás que aprender a hacer males de ojo y hechizos.

Are you ready to destroy and burn the present in order to create the real connection with la tierra?

Para crear esa conexión hay que mover, quemar y hacer cenizas los caballos.

Y lo que pase después, tendremos que descubrirlo juntes.

Are you ready for the commons for real? Are you ready to become a real witch? Are you ready to destroy and burn the present in order to create the real connection with la tierra?

Are you ready to build the commons? Y ojo que the commons is not el concepto de common que conociste toda tu vida. Lo común es la tierra, las plantas, el choclo y las estrellas. It is what is between you and me, between in this space in which you read and accept what I tell you.

Are you ready to become a real witch? Because in order to build the commons, you’ll have to learn how hacer males de ojo y hechizos.

Are you ready to destroy and burn the present in order to create the real connection with la tierra?

To create that connection you have to move, burn to ash all the bronze horses.

And what happens next, we’ll have to find out together.

Este texto ha sido escrito gracias a las conversaciones con Mauricio Adasme, poeta y diseñador grafico chileno con quien he colaborado ha distancia durante el estallido social de Chile.

This text has been written thanks to conversations with Mauricio Adasme, Chilean poet and graphic designer with whom I have collaborated from a distance during the social uprising in Chile.

Notes

- Del mapudungún watra, vientre, panza.

- From mapudungún watra, belly, stomach.

- Pacos, en Chile se refiere a los carabineros (policías). Se dice que viene del quechua p’aku, que significa rubio, castaño. No existen certezas sobre el origen exacto de la expresión pero en Argentina, Colombia, Chile, Ecuador y Panamá, los gendarmes fueron llamados pacos por el color de su uniforme: « ponchos pacos », un poncho de color rojizo cuyo material venía de la alpaca.

- La araucaria, cuyo nombre en mapudungun es Pewén o Pehuén, es uno de los árboles sagrados del pueblo mapuche, en especial de los pehuenches.

- Pacos, in Chile refers to carabineros (policemen). People say it comes from the Quechua p’aku, which means blond, brown. There is no certainty about the exact origin of the expression but in Argentina, Colombia, Chile, Ecuador and Panama, the gendarmes were called pacos because of the color of their uniform: “ponchos pacos“, a reddish poncho whose material came from the alpaca.

- The araucaria, whose name in Mapudungun is Pewén or Pehuén, is one of the sacred trees of the Mapuche people, especially of the Pehuenches community.

- Ser chica/e/o como expresión, se utiliza en Chile para referirse a ser más joven, en este caso, adolescente.

- Wenufoye (Canelo del cielo) es la bandera de la nación mapuche, elegida en 1992 luego de un llamado hecho por la organización mapuche Aukiñ Wallmapu Ngulam o Consejo de Todas las Tierras a confeccionarla.

- Bandera de chilena de color negro, icono que nació luego del 18 de octubre 2019, post estallido social.

- La Wiphala es la bandera de los pueblos andinos, usada en Bolivia, Perú, Colombia, Chile, Ecuador, Argentina y Paraguay. Popularmente, el nombre se cree de origen aimara y quiere decir «el triunfo que ondula al viento».

- Wenufoye (Canelo del cielo) is the flag of the Mapuche nation, chosen in 1992 after a call made by the Mapuche organization Aukiñ Wallmapu Ngulam or Council of All Lands to create it.

- Chilean flag of black color, icon that was born after October 18, 2019, post social uprising.

- La Wiphala is the flag of the Andean pueblos, used in Bolivia, Peru, Colombia, Chile, Ecuador, Argentina and Paraguay. Popularly, the name is considered to be of aimara origin and means “the triumph that undulates in the wind”.

- Wallmapu (en mapudungun: wall mapu, walh mapu, o waj mapu, ‘territorio circundante’) es el nombre dado al territorio que los mapuches habitan y habitaron históricamente el pueblo mapuche. El Wallmapu comprende desde el río Limarí por el norte hasta el archipiélago de Chiloé por el sur —en la ribera sudoriental del océano Pacífico— y desde la latitud sur de Buenos Aires hasta la Patagonia —en la ribera sudoccidental del océano Atlántico.

- La Ocupación del Wallmapu, o bien “Pacificación de la Araucanía” es el proceso de invasión por parte del Estado Chileno a fines del siglo XIX al Wallmapu, cuyo fin era reducir apropiarse de territorios indígenas a lo largo del país, para luego traer colones europeos a explotar dichas tierras. https://www.gamba.cl/2015/08/la-ocupacion-del-wallmapu-la-invasion-chilena-a-territorio-mapuche1/#:~:text=La%20ocupaci%C3%B3n%20del%20Wallmapu%3A%20La%20invasi%C3%B3n%20chilena%20a%20territorio%20mapuche

- El Lonco Külapang, (en mapudungun) fue un lonco mapuche que vivió en el siglo XIX y llegó a ser unos de los ñidol longko (jefes principales) que lideraron a las fuerzas mapuches que se opusieron al Ejército de Chile comandado por Cornelio Saavedra Rodríguez durante la ocupación de la Araucanía.

- Wallmapu (in Mapudungun: wall mapu, walh mapu, or waj mapu, ‘surrounding territory’) is the name given to the territory that the Mapuche people inhabit and historically inhabited. The Wallmapu comprises from the Limarí River in the north to the Chiloé archipelago in the south – on the southeastern shore of the Pacific Ocean – and from the southern latitude of Buenos Aires to Patagonia – on the southwestern shore of the Atlantic Ocean.

- The Occupation of the Wallmapu, or “Pacification of Araucania” is the process of invasion by the Chilean State at the end of the 19th century to the Wallmapu, whose purpose was to reduce the appropriation of indigenous territories throughout the country, and then bring European colones in order to exploit these lands. See: https://www.gamba.cl/2015/08/la-ocupacion-del-wallmapu-la-invasion-chilena-a-territorio-mapuche1/#:~:text=La%20ocupaci%C3%B3n%20del%20Wallmapu%3A%20La%20invasi%C3%B3n%20chilena%20a%20territorio%20mapuche

- Lonco Külapang (in Mapudungun) was a Mapuche lonco (leader) who lived in the 19th century and became one of the ñidol longko (main chiefs) who led the Mapuche forces that opposed the Chilean Army commanded by Cornelio Saavedra Rodriguez during the occupation of Araucania.

- En este caso, me refiero a Violeta Parra, artista chilena, conocida como una de las principales folcloristas en América del Sur y divulgadora de la música popular de su tierra.

- Plaza Dignidad es una plaza que se ubica en el corazón de Santiago de Chile. Originalmente se llamó Plaza Baquedano, en honor al monumento del Militar Manuel Baquedano que se encuentra centro del lugar. En el contexto de las protestas del 2019, la plaza fue renombrada como Plaza Dignidad por el movimiento en contra de las injusticias sociales producto de la estructura neoliberal del país. Para mas información sobre el «estallido social» https://www.openglobalrights.org/chile-and-a-global-revolution-for-dignity/

- Desde la revolución de octubre 2019, la estatua de Manuel Baquedano ha sido el epicentro de las protestas de Chile. Este 8M, entre medio de las conmemoraciones feministas, los intentos por derribar al caballo fueron tantos que el estado de Chile decidió retirarlo, luego de que la gente intentó quemarlo y cortarle un pie para desestabilizarlo y con eso hacerlo caer del podio. Sebastián Piñera, decidió mover la estatua, retirarla para ser restaurada y cerrar el podio con una pared de cemento para parar las manifestaciones. https://www.eldesconcierto.cl/nacional/2021/03/08/videos-dispersan-marcha-del-8m-tras-nuevo-intento-de-derribar-estatua-de-general-baquedano.html

- La Alameda, ahora llamada Avenida Libertador General Bernardo O’Higgins es la principal avenida de Santiago de Chile y también principal lugar de protestas de la capital.

- In this case, I am referring to Violeta Parra, Chilean artist, known as one of the main folklorists in South America and spreader of the popular music de su tierra.

- Plaza Dignidad is a square located in the heart of Santiago de Chile. It was originally called Plaza Baquedano, in honor of the monument of the military officer Manuel Baquedano that is located in its center. In the context of the 2019 protests, the square was renamed Plaza Dignidad for the movement against social injustices resulting from the neoliberal structure of the country. For more information on the “estallido social,” see: https://www.openglobalrights.org/chile-and-a-global-revolution-for-dignity/

- Since the revolution of October 2019, the statue of Manuel Baquedano has been the epicenter of Chile’s protests. This 8M, in the midst of feminist commemorations, the attempts to topple the horse were so many that the state of Chile decided to remove it, after people tried to burn it and cut off a foot to destabilize it and with that make it fall from the podium. Sebastián Piñera, decided to move the statue, remove it to be restored and close the podium with a cement wall to stop the demonstrations. https://www.eldesconcierto.cl/nacional/2021/03/08/videos-dispersan-marcha-del-8m-tras-nuevo-intento-de-derribar-estatua-de-general-baquedano.html

- The Alameda, now called Avenida Libertador General Bernardo O’Higgins is the main avenue of Santiago of Chile and the main place of protest in the capital.

Back to summary

Back to summary