What’s with the Gimmick?

Abstract

Drawing on Sianne Ngai’s Theory of The Gimmick: Aesthetic Judgment and Capitalist Form (2020), this essay examines the reception of fashion collective Vetements through the lens of the gimmick, discussing the label’s infamous DHL t-shirt as a prime example of a design that simultaneously “overperforms” and “underperforms.” An aesthetic judgement, the gimmick triggers an estimation of both an excess and a lack of labor, which, in Ngai’s words, reflects an “uncertainty about time and value.” Connecting the DHL t-shirt to the state of creative labor in the industry, the essay foregrounds the engagement of design with issues surrounding labor.

Text

In an interview with The White Review following the release of her book Theory of the Gimmick: Aesthetic Judgment and Capitalist Form (2020), the cultural theorist Sianne Ngai was asked about the shunning of ambivalence in contemporary criticism. She explained, “I think ambivalence is less important as an attitude one brings to the things one studies — though it certainly is that — than as an affective situation already encoded in the specific kinds of aesthetic phenomenon that I pay attention to.”1 The Vetements label and its infamous DHL t-shirt, which debuted at its Spring/Summer 2016 show, are fashion phenomena that strike me as representative of the encoded ambivalence that Ngai has explored over the past fifteen years. The industry was uniquely divided about the collective led by Georgian designer Demna Gvasalia: Some believed that Vetements had staged a revolution,2 while others merely perceived the image of a revolution.3 Either way, discussions of the brand’s self-conscious deployment of meme culture and copy made a strong case for the brand’s significance.4 Nevertheless, I felt a piece of the puzzle was missing.

I have ruminated on the label’s impact ever since it erupted onto the Parisian scene, and I have grappled with conflicting feelings. On the one hand, I was exasperated by the brand’s predictability. Its strategy seemed worn out and its ornamental use of subculture so blatant that the notion that Vetements had “staged a coup” seemed ludicrous. On the other hand, I felt that the label somehow warranted attention. I had a nagging feeling that it could not just be left to rest — that, for some irritating reason, its story said something important about our current moment.

Then, I encountered Ngai’s Theory of The Gimmick. Her weaving of affect theory and aesthetics offered a particularly compelling perspective from which to approach the label. It allowed me to consider the label through the very feeling that it elicited in me: ambivalence.

Claims to worth

Gimmicks are first and foremost the result of an evaluation, a judgment about the value of the thing — the gimmick — we are confronted with. It goes without saying that the term connotes a negative experience. However, for Ngai, the gimmick also at times “compels fascination.”5 In this, it perfectly captured the feeling the brand elicited: ambivalence. As Ngai makes clear, the judgement it registers is aesthetic in nature but connected to economic concerns. I was confronted with this realization in very prosaic terms. My first conversations about the t-shirt revolved around its price: How could the label justify selling a t-shirt, a copy at that, for as much as $300? This question was also at the center of some of the press coverage at the time. However, I remember feeling somewhat stunned that the collection’s worth had inevitably circled back to debates over price tags. Tangible experiences of value were suddenly weighing on an industry that rarely discusses value in such “crude” terms. Indeed, there seems to be a tacit agreement that the exorbitant prices are valid reflections of the “high” in high fashion. In Vetements’s case, that agreement had seemingly been broken.

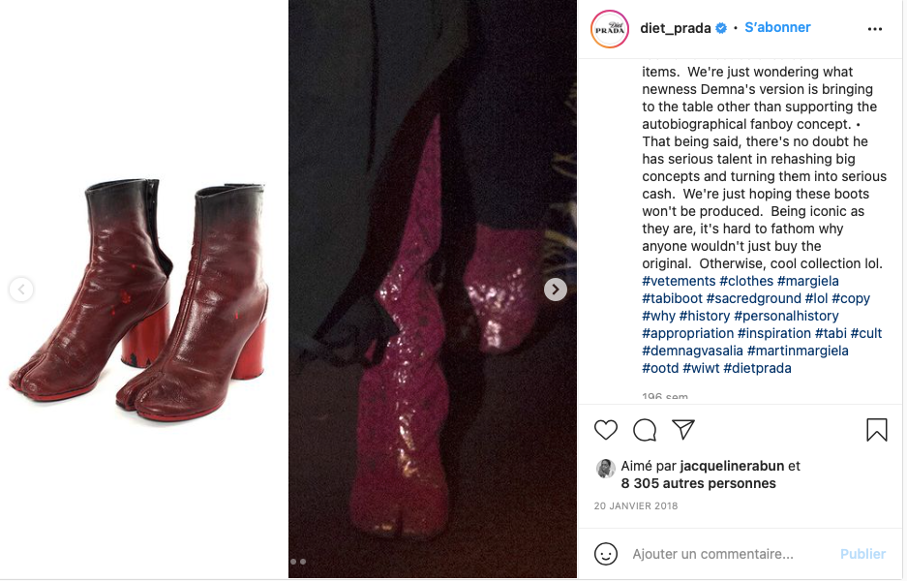

According to Louise Crew, “luxury products cannot be valorized or financialized by conventional methods”6 because they are, in the words of Lucien Karpik, “multidimensional, incommensurable and of an uncertain or indefinable quality.”7 In Vetements’s case, the capacity to capture a zeitgeist (the desire for pragmatism in the wake of too much glamour), a prestigious lineage (Gvasalia’s stints at Maison Martin Margiela and Louis Vuitton), and an “avant-garde” aura (its use of subcultural codes and affiliation with art practices) somewhat sustained that certain “indefinable quality” of high fashion since “high skilled and artisanal craft production and a fixed geographical manufacturing identity” have mostly ceased to define it.8

As an emerging ready-to-wear label, Vetements was not entirely beholden to the criteria that symbolically define the ready-to-wear collections of heritage houses, whose couture traditions uphold the veneer of old-time luxury. However, with its inflated prices, the label was apparently making claims about the worth of its “low brow aesthetic.”9 It’s claims to value were perceived as “blasphemous” both on aesthetic and economic terms.

Gimmicks, Ngai contends, “are overrated devices that strike us as working too little (labor-saving tricks) but also as working too hard (strained efforts to get our attention) … In our everyday encounter with the gimmick, we are thus registering an uncertainty about labor — its deficiency or excess — that is also uncertainty about value and time.”10 As a literal copy of the shipping company’s uniform, the DHL t-shirt, just like the gimmicks Ngai describes, simultaneously overperformed and underperformed. The label’s use of a copy, with its disregard for the symbolic trappings of the luxury market was indeed bound to “fail” as a luxury product, but it succeeded in attracting attention.

Looking back, it seems that what discussions about prices reflected then were a suspicion about the garment’s value based on the work it seemed to both lack and have in excess. In other words, judgments about the label’s expensiveness in relation to the actual garment hinted at a sense of unease or frustration with both the amount of work expended and the transparency of it all. The perceived lack of work applied both to the designer, as copy replaced design, as well as to its manufacturing, as t-shirts connote mass production. The label and the pieces were thus working too little but also too hard. The latter was apparent in the conspicuous disregard for the trappings of luxury, including the time spent laboring at it. Add to the mix the label’s perceived uses of art practices (the idea of the “ready-made”11) and subcultural codes (“Vetements: Whiffs from the underground” read a review in Business of Fashion12), and the effect is “an uninvited transparency about how it is producing what we take to be its intended effect.”13 All in all, this fed the suspicion that the label’s hint of the subversive was a ploy to achieve rapid fame rather than a desire to turn the industry on its head14. These tensions are apparent in an exchange between Highsnobiety journalists Alec Leach and Aleks Eror:

Aleks : […] The DHL T-shirts look like something your dad was given in some PR goodie bag and now only wears around the house. It’s supposed to look so incredibly blasé, so effortlessly cool, when in fact it’s the exact opposite. They haven’t picked a brand at random, they’ve thought through to find something that inspires feelings of ironic indifference. Serious, co-ordinated thought has gone into this. This shows that they very much do care about being cool, and take fashion very seriously.15

Prior to this comment, Eror had complained that the label was “charging Givenchy prices for ill-fitting Slipknot concert merchandise.” The aesthetic of “effortlessness,” and its practice in the form of copy, was then simultaneously an “overworked” aesthetic and lazy work.

Ngai notes that the gimmick “can be an idea, a technique, or a thinglike device.”16 The DHL t-shirt is an idea, which is the basis for its value in the eyes of critics (the t-shirt as ready-made or concept), and both a “technique” (a strategy) and “thinglike device”(a design) in the hands of designers embattled in a race to achieve fame and transform it into sales. The piece was indeed one of the early instances of viral fashion.17

As Synne Skjulstad argues, “a polarizing visual aesthetics can nudge audience labour and stimulate audience activity needed for heightened visibility on the platform [Instagram].”18 What Ngai’s theory of the gimmick helps clarify is the nature of the polarization that the label elicited in the uncertainties it both directly and indirectly raised about labor, time and value.

Breaking the spell

The Vetements brand had emerged from a deep frustration with fashion, which was seemingly as much about its aesthetic at the time, one dominated by high glamour, than the work itself, as Demna made clear in an interview with fashion journalist Alexander Fury:

“We used to meet up and have these frustrated, horrible talks about fashion!” Gvasalia recalls. “Hating everything, hating our jobs…” The antidote to all that was Vetements. The brand was launched from Gvasalia’s Paris bedroom, the product of weekends and nights spent designing for the love of it. “It was meant not to be a commercial project, because we didn’t have time and all of us worked,” he says.19

While Gvasalia has never expanded on the topic, his early admission that work was less than satisfying seems to resonate with the well-documented albeit rarely publicly discussed trappings of labor in the fashion industry: relatively low wages, long hours, and abusive bosses, conditions that were somewhat famously detailed by the anthropologist Giulia Mensitieri in her book The Most Beautiful Job in the World (2020).20 A key insight from Mensitieri’s work is that the overexposure of fashion causes the industry’s workers to accommodate precarious conditions solely for the sake of profiting symbolically from fashion’s media exposure and aura. As Mensitieri concludes, for a political project to emerge from these conditions, “it will be necessary first to ‘break the spell’ of the dream and of glamour.”21

Shortcut to the top

Whether borne out of intensifying frustration with excessive working hours and contracts or, as publicly acknowledged by the label, anger at the creative status quo — fashion’s privileging of glamour and image over people and clothes— what the Vetements label foregrounds is that the spell has long been broken. The gimmick is the arguably flawed but justifiable outcome of an overworked and bored creative lot. It has less to do with politics than business, and Vetements has never pretended otherwise.

As Ngai explains, the gimmick can function as an acquisitional tool and a strategic device “to enter work and mitigate its effects.”22 In this context, the brand-as-gimmick is a claim to a share of the profits and a shortcut to the top. This strategy has proven to be immensely successful for the collective’s leading figures: Demna Gvasalia has secured one of the fashion industry’s most coveted positions as creative director of Balenciaga, and early Vetements collaborator Lotta Volkova is now among the most high-profile stylists in the industry.23 Meanwhile, Demna’s brother, Guram Gvasalia, gets to profit from the residual fame of the Vetements brand.

The aim here is less to suggest that the label was always intended as a gimmick but to hint at the conditions that rendered gimmick-like designs a salutary escape — or in this case, a way in. When read against the industry’s state of affairs — the centralization of power and profit in the hands of conglomerates,24 the precarization and casualization of labor among its privileged class of workers, and the valorization of hard work in the name of creativity — it is hard not to view Vetements’s aesthetics as engaging, directly or indirectly, with (creative) labor in the era of conglomerates and networked media.

In fact, Vetements had literally put the creative worker on the catwalk. Demna has openly admitted that many of the brand’s designs were directly inspired by his collaborators.25 Moreover, Volkova has modeled in many of the shows, and the styles of employees — or whoever visited the studio, including DHL employees — were reproduced in designs. Suddenly, it was possible for the designers to actually profit from their symbolic capital as members of the creative elite. In fact, the brand’s early commercial success has demonstrated that there is perhaps nothing more aspirational than the look and the fantasized life of the creative worker.

Do you want to sell clothes?

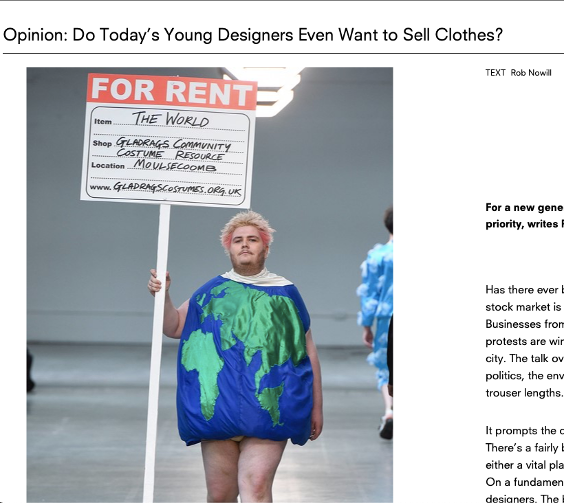

The gimmick has cropped up elsewhere in fashion. One example can be found in the Spring/Summer 2019 MAN show organized by the platform Fashion East, which supports emerging London-based designers. Of particular interest is the last Fashion East collection of Rottingdean Bazaar, comprised of James Theseus Buck and Luke Brooks. For it, the duo rented costumes from fancy dress shops around the UK and had the “looks” walk the runway with signs that described the item and identified the rental shop, its location, and its web details. Commenting on the show, the journalist Rob Nowill described Rottingdean Bazaar as “a label-slash-art-project-slash-in-joke”:

It was head-scratching. If it was intended as a commentary, the designers weren’t saying on what: reviewers at the time were given little in the way of explanation, and the designers did not respond to an interview request for this piece … The reaction was mixed. At the time, American Vogue praised the “humanity and humour” of both [Rottingdean Bazaar and Stefan Cooke], while The Guardian called it “fun, funny and riotous”. But others in the crowd groused that their antics were juvenile, and attention-seeking, and gimmicky. What’s the point, they asked, in dragging a load half [sic] of the industry out — on a Saturday morning — to see clothes that can never be reproduced.26

What was perceived as a prank by some arguably served to mitigate the workload (and, inevitably, the cost) involved in a collection. Indeed, stylists had all the information in hand to hire the pieces, saving the duo having the reply to demands and send-off their looks. Complaints that the show felt “gimmicky” seemingly related to the amount of labor one expects of emerging designers. Pragmatism, when it comes to time and labor, is a contentious choice in an industry whose (self-)perception depends on labor-intensive processes, or at least on upholding its image. The bragging of heritage houses about savoir-faire and, specifically, the number of hours a gown requires, especially in the context of Haute Couture, is indicative of the importance of labor and time in the evaluation of fashion’s worth. However, brands are more than happy to avoid discussing matters relating to labor when it comes to the mass-produced products on which the luxury industry makes its fortunes.

Laugh on

The fashion segment of the popular French infotainment television show Quotidien provides several other examples of “fashion gimmicks.” The segment, led by the fashion journalist Marc Beaugé, ends with a satirical “shopping idea,” whereby the latest fashion pieces are mocked for both their ugliness and their failure to embody the idea of luxury, of which Beaugé — with his specialist knowledge — is the guarantor. Frequent targets include products from Balenciaga, Off-White, Bottega Venetta, and Louis Vuitton, and the segment often features luxury items that are “upgrades” of cheap, generic products, such as Balenciaga’s version of Crocs shoes. The price of the item is usually revealed after soliciting guesses from the other journalists on set and typically evokes a mixture of bafflement and indignation from the audience.

The public mocking of fashion as gimmick is symptomatic of the feelings it elicits: We love to hate it. However, it begs a number of questions: Who is actually laughing? Who is working?27 And what is the nature of that work?

In her book Sensoria, media theorist McKenzie Wark argues that the aesthetic categories that Ngai outlined in her previous work — the cute, the zany, and the interesting28 — are perhaps less symptomatic of capitalism than of “an early something else,”29 which Wark explored more fully in Capital Is Dead. Is this Something Worse? (2020).30 Wark contends that “it is not quite the same to be making the old things and to be making new information.”31 Vetements’s meta-commentary on creative work and the rise of fashion “gimmicks” more broadly may be indicative of such a shift. However, for now, value, for independent brands at least, is only realized when viral circulation segues into the sale of a tangible commodity — or secures one a paid contract, whether that be for LVMH or Google.

This is an edited and updated version of an essay initially published in Dune Vol. 002 No. 002 “Value”, December 2021.

Notes

- Kevin Brazil, “Interview with Sianne Ngai,” The White Review, October 2020, https://www.thewhitereview.org/feature/interview-with-sianne-ngai/

- Alexander Fury, “The Label Vetements Is the Most Radical Thing To Come Out of Paris In Over A Decade. So What’s The Big Idea?”, The Independent, October 16, 2015, https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/fashion/features/label-vetements-most-radical-thing-come-out-paris-over-decade-so-what-s-big-idea-a6692211.html

- In an opinion piece for Vestoj, Anja Aronowsky Cronberg argued that the label and the mainstream fashion press’s aggrandizing statements about it fit an age-old pattern of the outsider usurping attention from the industry’s established names, with “whiffs from the underground,” only to play better by the same rules. Anja Aronowsky Cronberg, “The Revolution Will Be Branded Vetements,” Vestoj, http://vestoj.com/the-revolution-will-be-branded-vetements/

- As a blogger behind one of Archivepdf’s “deep dives” into the fashion meme put it, “The alignment of fashion memes and the brands that they make fun of can be defined by one trailblazer in the fashion world: Demna Gvasalia. He is honestly the OG Meme Lord. As the founder of Vetements and current creative director of Balenciaga, Demna has made a living utilizing meme culture to his advantage.” Casino Riv, “Fashion Meme Deep Dive, Part 1: Falling Down the Rabbit Hole of Degeneracy,” Archivepdf, https://www.archivepdf.net/post/fashion-meme-deep-dive-part-1-falling-down-the-rabbit-hole-of-degeneracy

- Sianne Ngai, Theory of The Gimmick: Aesthetic Judgment and Capitalist Form (London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2020), 8.

- Louise Crew, The Geographies of Fashion: Consumption, Space and Value (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2017), 82.

- Lucien Karpik quoted by Louise Crew. Lucien Karpik, Valuing the Unique: The Economics of Singularities (Woodstock: Princeton University Press, 2010), 24.

- Crew, 83.

- Alec Leach, “I Tried Explaining Vetements to Someone who Hates Fashion,” Highsnobiety https://www.highsnobiety.com/p/explaining-vetements/.

- Ngai, 1–2.

- In her discussion of the DHL t-shirt, Guardian journalist Lauren Cochrane discusses Vetements’s practice in the context of Ed Ruscha and Marcel Duchamp.

- Angelo Flaccavento, “Vetements: Whiffs from the Underground,” Business of Fashion, October 2, 2015, https://www.businessoffashion.com/reviews/fashion-week/vetements-whiffs-from-the-underground.

- Ngai, 83.

- The claim that the label’s choice of name made explicit — the idea that Vetements was about clothes and not fashion — was in fact the equivalent of claiming to lie outside fashion (or capitalism) from deep within its belly.

- Alec Leach, “I Tried Explaining Vetements to Someone who Hates Fashion,” Highsnobiety https://www.highsnobiety.com/p/explaining-vetements/.

- Ngai, 51.

- Emma Hope Allwood, “How Clothes went viral,” Dazed, March 30th, 2016, https://www.dazeddigital.com/fashion/article/30561/1/the-fashion-meme-vetements-vetememes-viral-clothes-dhl.

- Synne Skjulstad, “‘My Favourite Meme Page’: Balenciaga’s Instagram Account and Audience Fashion Labour Online,” International Journal of Fashion Studies 8, no. 2: 239.

- Alexander Fury, “The Label Vetements Is the Most Radical Thing To Come Out of Paris In Over A Decade. So What’s The Big Idea?” The Independent, October 16, 2015, https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/fashion/features/label-vetements-most-radical-thing-come-out-paris-over-decade-so-what-s-big-idea-a6692211.html.

- Giulia Mensitieri, The Most Beautiful Job in the World (London: Bloomsbury, 2020).

- Mensitieri, 258

- Ngai, 23.

- Kettj Talon, “From Post-Soviet Style to Kanye West: The Rise of Lotta Volkova,” NSS-G Club, September 14, 2020, https://www.nssgclub.com/en/fashion/19610/lotta-volkova-stylist-post-soviet-kanye-west.

- Conglomerates LVMH and Kering are the industry leaders. In recent years, they have consolidated their power with new acquisitions — the most recent being LVMH’s purchase of the American jewelry company Tiffany & Co. — and high-profile appointments at the helm of their respective ready-to-wear and/or couture houses, most notably Virgil Abloh at Louis Vuitton and Demna Gvasalia at Balenciaga.

- In justifying some of Vetements’s choices of labels as collaborators for their 2017 show, Demna explained, “the people who work at Vetements don’t really wear designer fashion — a lot of these are the labels they wear all the time.” Sarah Mower, “Vetements Spring/Summer 2017,” Vogue, July 3, 2016, https://www.vogue.com/fashion-shows/spring-2017-menswear/vetements.

- Rob Nowill, “Opinion: Do Young Designers Today Even Want To Sell Clothes,” Another Man, January 4, 2019, https://www.anothermanmag.com/style-grooming/10672/do-young-designers-even-want-to-sell-clothes-stefan-cooke-edwin-mohney.

- Synne Skjulstad provides some clues. Skjulstad, “‘My Favourite Meme Page’: Balenciaga’s Instagram Account and Audience Fashion Labour Online,” International Journal of Fashion Studies 8, no. 2: 239.

- Sianne Ngai, Our Aesthetic Categories: Cute, Zany, Interesting (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2012).

- McKenzie Wark, Sensoria (London: Verso Books, 2020).

- McKenzie Wark, Capital is Dead: Is this Something Worse? (London: Verso Books, 2019).

- McKenzie Wark, General Intellect: Thinkers for the Twentieth-First Century (London: Verso Books, 2018), 116.