ISSUE #16 – Profession: creative worker

Artists and designers confront the challenges of work

Introduction

As you may already know, we have entered the VUCA (Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, Ambiguous) era. In this changing world, it is no longer possible to look more than two or three years ahead. The climate is changing, and along with it society, its habits and achievements. This is what the Anglo-Polish theorist Zygmunt Bauman called the ‘modern liquid’ society: people behave in situations that are changing even before their behaviour can become a habit. The ‘solid’ era of production is followed by the fluid and uncertain era of consumers, who are unable to draw any lasting lessons from their experiences, as the framework and conditions in which their experiences take place is constantly changing.

Is this frenetic pace of change behind the Big Quit phenomenon? In the wake of the Covid crisis, more than 4 million Americans resigned and many filmed themselves on TikTok as they did so. The Chinese social network quickly became a forum for citizens to discuss work; a topic garnering a total of more than 50 billion views. At the heart of the debate is the meaning of commitment and self-sacrifice in the professional sphere, with this question coming up again and again: Covid having redefined work’s social dimension, what is the point of work now if it brings neither new experience nor well-being?

Derived from the Latin ‘tripaliare’ – literally ‘to torment, to torture with the trepalium’ – ‘to work’ in Old French means ‘to make suffer’. As a transitive verb, it also means ‘to shake’ or ‘turn into’ (‘to work the dough’). Ideally, work would thus open up the opportunity for self-transformation through new experiences. However, as the number of burnouts soars, work must imperatively guarantee a certain quality of life. Companies know that this aspect, which now has its own acronym – QWL (quality of working life) – has become a prerequisite for any recruitment. In a world where we plan less and less, short-term happiness in daily life is prioritised over the accumulation of long-term goods – and it is a matter of demonstrating that this short-term happiness makes the long-term effort worthwhile.

On the creative side, work stability is not an option and the VUCA world seems to have been a long-standing reality. Nonetheless, how a profession is defined and perceived is also changing. How do creatives see their future today? What is their relationship to their career? Does this word even still have a meaning and, if so, what is it? Can we delegate and mimic a company’s roles, or must we invent an alternative to this type of work organisation? In 1973, the thinker of political ecology Ivan Illich drew attention to the risk of too much dependence on industry: ‘The individual’s autonomy is intolerably reduced by a society that defines the maximum satisfaction of the maximum number as the largest consumption of industrial goods. Alternate political arrangements would have the purpose of permitting all people to define the images of their own future’ 1. By advocating for ‘creative autonomy’ and a ‘convivial’ society based on free access to the tools of the community, Illich theorised the Generation Z’s crisis of meaning ahead of its time. Degrowth, well-being, climate change and the precariousness of assets: designers’ and artists’ relationship to work is being reinvented just as their contributions seem more essential than ever when thinking about the future. This feature brings together critical contributions from HEAD alumni and teachers, giving the floor to those who question this relationship to their profession.

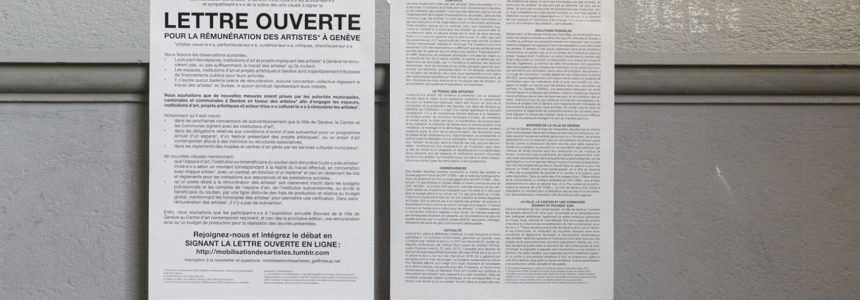

In an interview, the graphic designer Etienne Mineur comments on his exploration of image generation platforms, speculating on the evolution of the creative professions in the face of the automation of drawing. Aude Fellay and Emilie Meldem together with Giulia Mensitieri, author of Le plus beau métier du monde (2018), discuss how to create alliances in the fashion industry between creatives and the production workforce. In two of her films, the artist and alumna Lou Cohen explores the contemporary professional world with wry humour. From recruitment agencies to start-ups, she imagines situations where coaching and power relations combine and clash at the expense of workers’ performance of the self. In her TRANS Master’s thesis, of which we publish large excerpts, Eva Meister looks back on her daily life as a student, dictated by the need to finance her studies through odd jobs. Curator and alumna Julie Marmet returns to the Wages for Wages Against movement and takes stock of artists’ salaries. In a series of paintings and installations, Yoan Mudry questions the globalised representation of work on Google.

Enjoy!

Cover image: still form Alexandre le bienheureux, Yves Robert, 1968. © Gaumont