Femmage to Marion von Osten

The late artist-curator is remembered by Lucie Kolb, Pauline Boudry and Doreen Mende

Abstract

This article pays tribute to the artist, exhibition organiser and researcher Marion von Osten, who passed away in November 2020. A pioneer both in the field of research-based practice and in her decolonial approach to modernity, von Osten taught for several years at the HEAD – Genève’s research programme, CCC. Doreen Mende discusses von Osten’s influence on the programme, while Basel-based editor and researcher Lucie Kolb points out how von Osten always sought to connect the concerns of arts programming to the material base in which the art itself was rooted.

Text

In conversation with Marion von Osten

I remember a conversation with Marion at the restaurant Piccolo Giardino in Zurich when we were preparing a research project on institutional practices. We sat outside; it was sunny. While talking, I had to hold my hand in front of my eyes to see her face. Drawing on her text “The End of Contemporary Art (As We Knew It),” we wanted to study the collectives she called micro-organizations. Such organizations seemed to understand how to avoid pitfalls: between local and international, between art and activism, between fixation and openings. When I brought up Shedhalle Zurich, she waved it off: “The 1990’s, that was a different world.” I wish I asked what she meant by that.

What intrigued me about Marion’s work at Shedhalle was how infrastructural work seemed to be ever as important as programming. And how subject matters – whether a review of feminism of the 1970s, an investigation of sexualized public sphere, of counter-information in the digital sphere, or the border politics of Europe – always aimed at linking art, theory and practice. The exhibitions stemmed from long-term working groups, whose work manifested itself in various forms. The exhibition itself was not necessarily considered the end of a shared thinking and working process. It was one moving part of it. Such a process-based approach to exhibition making raised critical questions as to how we engage with exhibitions and institutions.

We started talking about one of her texts from that time, which I had republished on Brand-New-Life, and in which she reflects on the 1990s. We talked about the figure of the cultural producer, forms of engagement that aimed at a context other than that of art, while at the same time asserting that this is precisely what comes within the purview of art; forms of engagement that transgressed prescribed areas of responsibility and traversed theory, criticism, mediation, organization, curating. Marion wrote about the cultural producer with Brigitta Kuster and Isabell Lorey, as kleines postfordistisches drama (kpd). For her, the cultural producer was some type of postcapitalist subject, who by crossing lines of responsibilities makes the distribution of competencies and responsibilities visible. This crossing would leave traces, cracks, injuries in conditions of production by traversing different work settings, ways of thinking, research agendas, ways of making something public.

Later, we attended an event, celebrating a book dedicated to Marion’s practice titled Once We Were Artists (2017). Published by Tom Holert and Maria Hlavajova, the book discusses her practice as one that détourned the figure of the artist. I remember her joy and discomfort as people talked about her, about her thinking and doing, about how she mapped out a new field of practice. Joy because the book collects essays by numerous friends. Discomfort because the book engages in an art historical reflection on her practice while she was working to rewrite that mode into a practice-based theory.

I first learned about the figure of cultural production in the early 2000s while studying visual arts. This period was marked by a professionalization and academization of practices such as Marion’s under labels including “artistic research” or “critical studies.” New study programs drew from research-based artistic practice developed in dialog with activist, subcultural and academic fields and put forth practices transgressing established disciplines of knowledge. Trained as an artist, I now work in a practice-based transdisciplinary research field, between contemporary art, media and cultural studies, where the questions raised by the figure of the cultural producer are ever as virulent: How can we situate ourselves critically in neoliberal labor society, which, as Marion points out in her PhD “In the Making” (2018) abstracts the worker from his or her means of production and abstracts creativity and project work from the larger context in which it takes place, as well as claims the exclusivity of knowledge as property? The potential of the figure of the cultural producer today lies exactly in the ways it aims at redistributing knowledge. It brings activist and feminist knowledge into appearance and, in doing so, shifts the demarcation between legitimate knowledge and illegitimate knowledge.

The conversation is one site of illegitimate knowledge. It is messy, potentially all over the place. It is a place where we reach out to find connection, where we let the other in and in reverse take part in the other’s thinking. Where we play together, and in playing create a shared practice. In exchange, one develops a shared understanding, practice, and world. In conversation, one creates openings for the possibility of collective practice. A conversation can yield relations, cultures and ethics. It can map out a path, guiding and orienting us. Conversations leave traces, evidence of former conversations. Being in conversation with Marion had a formative effect on me. It opened up the possibility of instituting away from the settled conventions of the artist, contemporary art and its institutions.

Lucie Kolb

Photo souvenir

I had the chance to work with my friend Marion von Osten at the Shedhalle, just after I finished my studies at the HEAD. I was involved in the development of her projects from 1996 to 1998. Every day was an adventure; putting together exhibitions, film programmes, publications and debates – the results of collaborations between ephemeral but carefully assembled groups of artists, thinkers and activists. I was nourished by the critical conversations, the anti-hierarchical and anti-institutional approach, her solidarity and humour.

Pauline Boudry

Dear Marion,

“It was this change in practice—acting in public independently, even if on a small, self-organized scale, and insisting on the continuity of a hybrid and open-ended practice and of our work-life relationships—that had become an urgent need for research-based practice involved in the process to decolonialize culture production.” p. 185.

“An inter-arts perspective […] is central to my own practice.” p .194.

Marion von Osten, In The Making: Traversing the project exhibition In the Desert of Modernity. Colonial Planning and After, doctoral thesis, Lund University, 2018.

When a friend passes away, either one can handle one’s own grief by supporting her/his/their closest ones, or one must mourn by oneself with little capacity to support the family. I think, this time, I painfully belong to the latter while I will keep trying to be a support.

Our first encounter in the context of CCC took place during the diploma-jury in June 2015. You were one of the members of the jury responding to the presentations of graduating CCC students. For me, it was the second time to learn about some of the students’ work after my teaching demonstration as part of the hiring process and before starting my position as director of the CCC research-based Master program in September 2015. The graduating students presented their work ranging from feminist science-fiction to choreography at the seminar room 27 on Boulevard Helvétique 9. The audience including teachers, friends and the jury was spread around the room in a loose spatial order. I remember well where you were sitting: Situated in the middle of the room next to colleagues in continuous exchange with students, verbally or attentively, to ensure a pedagogical responsibility through a range of voices of which your voice stood out through a profound awareness for the student’s vulnerability in a situation of evaluation. Not that the other members would have been insensitive. Yet, I remember well your responses in English demonstrating your care for listening––you would perfectly also understand a presentation in French––while analyzing what had become audible/visible in relation to a time-space-specific situatedness by the means of art: An exhibition maker’s politics through a pedagogical setting.

Each of your response was a sensitive consideration to what degree your feedback could support and encourage, but also challenge and provoke, if necessary, the student’s presentation. Your response could be also demanding if you had the impression that the student would not have yet mobilized his/her/their possibilities to dive into a true process of critical thinking. You could get impatient when a student ignored or dismissed critique, thus, would insist in blindness of his/her/their privilege. I so appreciated your ability to confront such limits, yet, always turning limits into liminalities: Emancipation cannot claim purity, but is a process, a struggle, and a continuous oscillation of positions between right/wrong or good/bad.

While writing this down, it makes me think of ongoing conversations these days on the limits art as we used to know it. It brings to my mind the text Reading Art as Confrontation (2015) by Denise Ferreira da Silva or Four Theses on Aesthetics (2021) that Denise co-authored with Rizvana Bradley, that could be interlocutors for your proposal of in the making as a methodology to confront the coloniality of spatial-visual practices including the exhibitionary complex. How amazing it would be to discuss very current debates with you on the abolition of the exhibition, positionality and refusing research in relation to your proposals, dear Marion. Where could we realize such conversation against the inequality of life?

I remember well when you included your own situatedness, your own embodied knowledge of struggle into your feedback. It would break apart the teacher/student-divide: doing research as a practice of disrupting normative orders of knowledge is a continuous struggle that does not stop even for an internationally acclaimed artist, pedagogues, and exhibition-maker in practice. That was important to hear for the students from a woman with an active research-based practice across various geographies through contemporary art while also teaching! So was for me as well. I understood during that jury the beginning of a huge responsibility, institutionally but also emotionally, politically and intellectually, to be the next person responsible for the CCC counting organic intellectuals like you as a core member of the team of an outstanding research-based independent study program. CCC could reckon with your politics of pedagogy as one of care, collectivity and urgency, and if necessary, of confrontation. I learned so much from that approach, but also felt in this moment a sort of ‘coming home’.

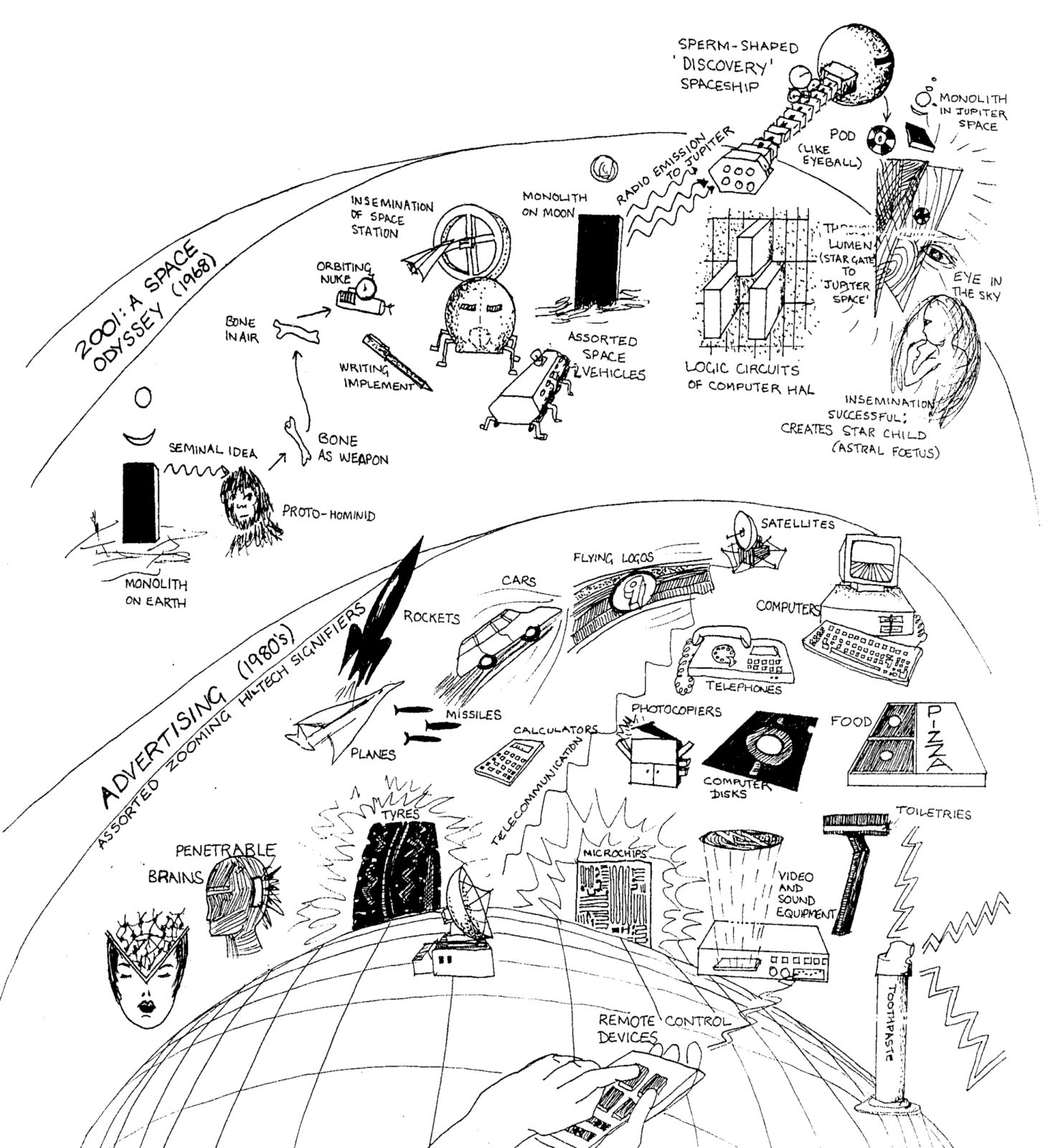

During that jury in June 2015, it was in fact the very first time that we talked extensively. Till then, we had heard each other’s work for years. Your work had been an important reference for my own curatorial imaginary. I remember well the exhibition In the Desert of Modernity Colonial Planning and After (August through October 2008 and publication Colonial Modern: Aesthetics of the Past Rebellions for the Future released in 2010) at the House of the World Cultures: you created a research-framework for investigating the architectural practices turning North Africa, specifically Algeria and Morocco, as spatial laboratories for an architectural colonialism of France, Germany and Switzerland that the anti-colonial architecture historian Samia Henni Architecture of Counterrevolution: The French Army in Northern Algeria (2017, translated/published in French in 2019) would define a decade later as psychological-material warfare by architectural means of imperial modernity. Thus, in that jury, there was the Marion von Osten sitting at CCC next to Yves Citton and Anna Gritching who all had been invited by the then interim-CCC-coordination Laura von Niederhäusern and Anne-Julie Raccoursier in conversation with the CCC-founding director Cathérine Queloz.

There was Marion von Osten, the artist-trained exhibition maker (you would not consider yourself a curator), who––since your years at the Shedhalle––brought to the CCC a pluriverse of post-colonial, feminist and anti-colonial thinking as the foundation for developing a practice of research as a process in the making. With your artistic formation, you would consider thinking and making always as sisters in arms for constituting an exhibition practice that insists on enabling a shared process while refusing the delivery of a product in the logic of primitive accumulation. In my first year, you continued to teach with Anne-Julie Raccoursier the seminar Situated Art Practices at the CCC. For me, you composed with Anne-Julie a dream-team that I gratefully and gladly ‘took over’ from the previous CCC team. I remember well one seminar session in which you introduced conceptual differences between oxymoron, metaphor, metonym, and allegory as operational framework for discussing what a research project might be. I remember that I would have liked to join your joint-seminar session, yet, I felt that it was important to leave the space to you and Anne-Julie also as an intimate stability resonating from the ‘old’ CCC.

Each time you came over to Geneva for your seminar, we would go for walks or dinners. During one of the dinners, in a restaurant at the lake, you shared with me you deep fear of falling ill, again, of cancer. I was not aware that you had survived cancer once. At this moment, around 2015/16, there was no danger of a second time at all. Medical check-ups did not detect any cancer marker! If I remember correctly, you were medically declared of being cured from cancer. We toasted on this fact, and real promise, with great joy while that joy for you must have always been entangled with an ambience of unpredictability.

During one of our dinners, you also talked about your research on the Bauhaus as a global history of migration by means of craft, art, architecture and education, as a history not of only one but many Bauhaus-es; this research still was in very early steps, yet, also a continuation of your project-based research around Colonial Modern.

During that first year, I initiated the Public Seminar as one of my first concrete activities for the CCC. This format became necessary for me after I realized the structural challenges that I might encounter upon my arrival in the transition from ‘old’ to ‘new’ CCC: for the Public Seminar, that I called Thinking Under Turbulence, I asked members of the CCC-team and/or Visual Arts department to be in conversation with invited external guests of my network that I had planned to bring to the CCC and to HEAD. Yet, logically, I could not just land like a satellite but had to create dialogues, conversations and––important also for myself–– spaces of listening to what exists, which questions will need to be deepened and what kind of conversations are necessary.

For one of the first session few weeks after my start, I asked you, dear Marion, to participate (with Anne-Julie) as contributors of the existing CCC-team to be in conversation with my curator-friend Grant Watson; Grant would present his curatorial research-project How We Behave inquiring the resonances of queer-intellectual thought at the U.S. West Coast traversing to Europe constitutive for art as a form if life. I thought that you both would constitute the perfect match. And: It was the perfect match! A year later, you both teamed-up as artistic directors of the transcontinental exhibition project Bauhaus Imaginista travelling to Lagos, Brazil, India, Morocco, Japan, China, Switzerland and Germany. Yet, aou and Grant met at CCC during ‘my’ first year for the first time: This first encounter contributing to the formation of a most beautiful and important travelling research-exhibition felt also like an all-futures blessing for bringing different networks at the CCC together. (Your contribution with Grant Watson for the CCC Public Seminar Thinking Under Turbulence in November 2015, which was responded by Yann Chateigné, is still available in the publication: https://head.hesge.ch/ccc/turbulence/wp-content/uploads/doreen-mende-thinking-under-turbulence-1.pdf)

In reverse, you always mentioned this first encounter whenever you introduced the genesis of Bauhaus Imaginista, in which you invited me to participate on account of my research on geopolitics and the curatorial in a world after 1990 through an East-South inquiry, an axis for situated knowledge that we discussed often together, and each time, I embraced, honored, admired and cherished your perspective, experience, collectivity and friendship.

There are endlessly many situations since Saturday, 14 November 2020, where I deeply long for our conversations, dear Marion, where I imagine what you would think. Or when I see your complicit gaze in front of my inner eye encouraging an early thought or confirming a critical judgment or simply making me feel supported in a debate (with male friends or colleagues). You cannot imagine how much your voice––also a feminine voice of a “warrior of the imaginary” as Patrick Chamoiseau proposed in the early 1990s––is present in these conversations, yet, missing. There are countless moments where I am longing for your sharp, sometimes harsh but always loving critique to bring an idea further.

In the context of CCC, you have been a major figure, a profound person of trust, also for me during that first demanding year at CCC-in-transition at HEAD Genève. You were full of a long-life friendship with the pre-2015-CCC. At the same time, you offered support, affection, vision and sisterhood to me: Thank you! You would believe in transgenerational coalitions that cannot be practiced without mutations, silences, and distances. Yet, always full of belief of sharing across our difference, as priority, to reach beyond ourselves in struggle for a better world. Everyone who has been in exchange with you––students, friends, colleagues and I would argue also opponents (if they existed, because I do not know anyone) –– must count themselves lucky. Your work continues to resonate, more than ever, and will do so with urgent relevance in the future. You initiated the conditions for that which we may consider curatorial/politics in the making as your practice-based doctoral thesis begins.

Written on 16 January 2022 in transit on the train ICE 371 to the Genève for the January presentations by 29 students of the CCC with the team, guests and friends.

Doreen Mende