Sustainability revisited

MA in Fashion and Accessory Design Thesis by Tara Mabiala

Text

Sustainability is a tricky field to navigate for fashion students: research is both plentiful and surprisingly homogenous when it morphs into industry talk. How do you move away from the well-trodden paths? How do you make an original contribution to such a crowded yet essential conversation? Sustainability Revisited: An attempted description of fashion futuring inspired by collective dress is just that – an attempt to think about sustainability less straightforwardly. It asks what sustainability looks like if what is on the table is our relationship to clothes, as opposed (or in addition) to their production. MA student Tara Mabiala’s thesis looks to self-care for answers. What started as a loose intuition that self-care had something to do with sustainability evolved into a full-blown text that wraps self-care around “collective dress.” The notion is something she develops from two historical case studies: the black women of the civil rights movement and punks. Here, she takes us through her argument, her material, and how sense is made of “messy” ideas.

Aude Fellay: Your thesis moves away from standard approaches to sustainability. You don’t see the problem as one that is simply tied to production or manufacturing issues. You decide instead to focus on the way we relate (or could relate) to our clothes, our sense of self and belonging. The notion of care here is critical. How did you first decide on this route? And how has the idea of care shaped your argument?

Tara Mabiala: I think the starting point was that looking at production and the sustainability of raw materials was quite obvious, and is something seen in cases of greenwashing. Having been brought up in different cultures I realised that relationships to clothing vary. The way we relate to clothing might be dominant, but it is not the only option out there, so looking at our relationship to clothing could be a way of thinking about sustainability. That was the first reason. Another was looking at what sustainability means in its most basic form, as a definition in the dictionary. I realised that if sustainability is about keeping things at a certain level then the notion of care must be a part of it. Care for nature and ecology, etc., but also perhaps for ourselves; being kind to ourselves through clothing…It brings this idea of care full circle.

A.F.: This makes me think of the work of design activist and researcher Kate Fletcher and her point that “durability, while facilitated by materials, design, and construction, is determined by an ideology of use.” So much so in fact, that “garments which defy obsolescence do so in informal or unintentional ways, rarely as a result of design planning.” The term “ideology” appears quite a bit in your work about collective dress. Can you talk us through what you mean by collective dress and how you use it?

T.M.: I took the idea of collective dress from the idea of uniforms. I make a distinction, however. I think collective dress is something that emerges organically out of social and cultural contexts. In other words, it is not something that is imposed. I see it as something that is shared by a group of people that have in common a particular “ideology,” a term I use here in its broadest sense. So rather than having a uniform create the group because people are asked to wear it, the group is created by adopting a collective dress as a way of presenting itself and its values. In a way, sustainability is an “ideology” and it is shared by quite a lot of people. One could ask what type of collective dress it translates into.

A.F.: It seems as if by opting for collective dress as a thread for your research on sustainable fashion, you are trying to create intentional ways of reconfiguring our relationship to clothes. To generate greater care – greater care for the earth, greater care of the self, greater care for clothing. What would a concrete implementation of a sense of collectiveness in dress look like? You mention in the introduction that you have been making some of your own clothes from a young age because it’s something that your Dad does. It feels like the anecdote is as much about the sharing as the making…

T.M.: I think this notion of an intentional relationship to clothing is very important: it is about choice and making some possibilities non-possibilities. Collective dress is about people who make a decision to dress a certain way; it is about individuals choosing to dress in a certain way. Looking at past examples of collective dress and how people have built their relationships to clothing can be a way of informing our personal decisions about dress. Changing our relationship to clothing doesn’t necessarily involve sharing. It is about taking a stance. My Dad made the decision to make his own clothes. Even if I am not ready to take on that “ideology” as actively, it has definitely trickled down and made me think about these questions on a theoretical level. I don’t know if we need spaces to physically share dressing or the making of clothes. A lot of people in the literature that I read talk about setting up workshops and creating new spaces for fashion…but maybe the space is verbal. It is about talking about our relationship to clothing.

A.F.: The idea of “collective dress” is also a way of fighting against the ways in which sustainability is usually placed on the shoulders of the individual. So I guess you use collective dress as an example of a type of “use” as Fletcher puts it, but also as a way of pushing against this tendency to place the responsibility of change on individuals. You were working on two fronts at once!

T.M.: Big industry leaders often place the responsibility of change on consumers. They are not pulling their weight. I do think, however, that social and cultural movements have a lot of power and can provide examples that pave the way for change. I believe strongly in this idea of leading by example. What I am against is big industry leaders asking individuals to bring old clothes so that they can get five pounds off their next purchase. It stops us from thinking about our relationship to clothes. It puts (green) words in our mouths but does not help us think about or reconsider our relationship to clothes. We are often told by people who could do more what to do. These steps from these companies are important but not radical enough.

A.F.: The second part of your essay focuses on collective dress. Reworking sociologist Georg Simmel’s theories about society’s perpetual back and forth between conformity and differentiation, you argue that dress is always to some extent a collective undertaking, or at least always involves some sort of collective dialogue. You dissociate people’s “need of union” from Simmel’s class-based analysis and recast people’s eagerness to conform into the more positive notions of belonging and community. Quoting French thinker Didier Eribon, you ask: “Isn’t singularity inevitably collective?” Here, your argument comes full circle, as this question draws you closer to Audre Lorde’s formulation of self-care. Can you explain this?

T.M.: I approached Simmel quite naively. I remember reading his work and thinking, this is exactly what I am trying to say. I kind of took Eribon and Simmel’s work at face value as I did not know much about the context of their work, but their ideas translated what I had in mind but hadn’t yet formulated… So for me, an individual is quite self-explanatory, but I do not think anyone is entirely or independently an individual, especially when it comes to clothing. An individual style always exists within something that already is – nothing is wholly original. Individuality is always something linked to some sense of collectiveness, whether acknowledged or not. This idea of a singularity being collective is something Audre Lorde puts forward with her famous quote: “Caring for myself is not self-indulgence. It is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.” It is implicit here that she refers to other black queer women. The idea that singularity is inevitably collective is really obvious to me, but it is perhaps not something we think about in everyday life… We are not sufficiently conscious of it…

A.F.: You then go on to examine different groups that have used collective dress in which, precisely, the question of self-care becomes tied to the idea of resistance, especially for the women of the black civil rights movements. You then look into punk subculture. Can you talk us through your choice of examples?

T.M.: Initially, I had a lot of different examples. The Rajneeshees, the Hypebeast (young people wearing hype brands), Emos… I finally decided to stick to two cases. The black women of the civil rights movements was a choice that was quite personal. It is an interest I have had for a very long time, and I have read a lot on the subject. There is one book that I use in my thesis titled Liberated Threads: Black women, style and the global politics of soul by Tanisha C. Ford, which was a bit of a revelation. The title says it all really. The black women from the civil rights movement, particularly the women from the SNCC (Student Non Violent Coordinating Committee), had a very thoughtful approach to clothing – they used it strategically. They are a very good example of how we can relate more consciously to our clothing choices. And when you say “punk” everyone has a mental image of what that looks like, and it is actually quite accurate. They had a powerful visual vocabulary that was also tied to an identifiable ideology in some sense, so both examples conveyed quite clearly what I wanted to say. The other examples have a trickier side to them. The notions of radicalism and resistance were important, but I think it is also possible to make a case for collective dress without them.

A.F.: At the end of your chapter on the black women of the civil rights movement, you bring in Solange, and her performance at the Guggenheim museum. You note that she was highly aware of the whiteness of the context – the museum – and its regime of exclusion. You quote her saying that “inclusion isn’t enough.” I feel this strongly resonates with the limitations of “respectability” you discussed about the SNCC (Student Non Violent Coordinating Committee). Can you explain what role this idea of “respectability” played in the SNCC’s approach to clothing? And in what ways do you feel that Solange is fighting against that “respectability”?

T.M.: This idea of respectability is two-faced. The women of the SNCC, one of the leading organisations of the movement, had to dress respectably for the people who saw them march. The crowd was probably a mix of white people and black sharecroppers. They had to navigate what was deemed respectable. They had to perform being respectable for their message to be received in a certain way, so they had to be strategic about their choice of clothing. Solange reclaims this in a sense and perhaps shares some of the same questions I have. The context being different, I guess she can be more “punk,” more radical. By punk, I mean Vivienne Westwood’s idea of “confrontational dressing.” Solange is aware of the context but pushes against it, all the while remaining “respectable.” Solange and the women of the SNCC navigate what is considered acceptable by society at those different times, and decide strategically on how to dress to best communicate their message. Solange can be more confrontational today: what she says and voices so strongly probably makes a lot of people angry.

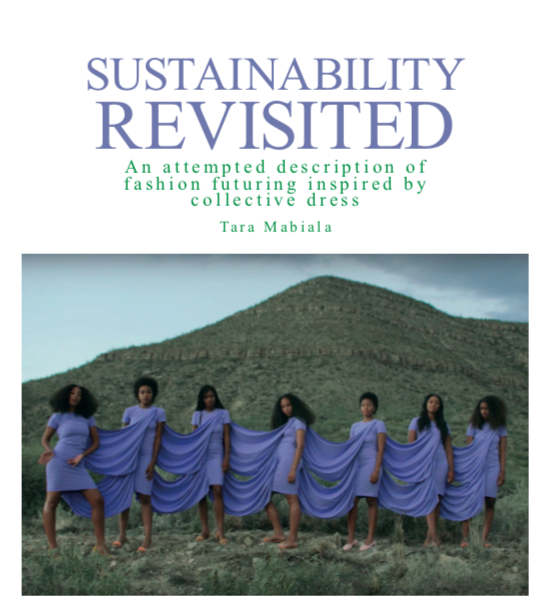

A.F.: There is a tension between having to be respectable in order to be heard and knowing that respectability doesn’t grant you equal treatment…. An image from a Solange clip is featured on the cover of your thesis. Solange and her performers are all dressed in the same colour, an intense shade of purple. It reminds me of the first image you showed me when you first started working on the subject, a photo of the Rajneeshees. Do you remember it? Can you explain why you were first attracted to it, and how the use of colour in clothing relates back to the idea of self-care?

T.M.: I am quite instinctively attracted to colourful clothes and images. There are so many theories on colour… how colours are meant to make you feel, which colour complements your skin tone, etc. It was the type of discourse you find around semi-precious stones, in which I got interested at some point. Then I watched a documentary about the Rajneesh movement. I was visually seduced by their choices of colour – mostly different shades of red. I did a bit of research on them, and I realised their colour choices were really important and reflected their ideology (passion, the sun, etc.). Wearing those colours made them fully embrace their “ideology,” which is something I find interesting. The way I react to images is based on pleasure. I don’t theorise as to why I like certain images. I don’t think I am satisfied with my work until I can actually feel a sense of pleasure looking at it and I have realised this pleasure is often tied to the colours I use.

A.F.: The visual pleasure one gets from the images you pick resonates with the sense of pleasure self-care produces… Hanging on to pleasure is pretty counterintuitive to the way in which durability is usually discussed, but feels rather important…

T.M.: I think this idea of pleasure, of pleasure in images, is essential. I am quite happy to design images that produce that feeling for other people. In design, in the actual process of designing, I like creating an atmosphere based on pleasure. I am thinking about this at the moment as I put together the collection for my Master’s degree. I have conceived it as a manifesto in favour of dressing up and taking pleasure in the act of dressing. It is about being proud of dressing and being proud of oneself. Clothes can give a particular posture and sense of self to people. It is not about dressing how you feel; clothes can make you feel what you want to feel. You can think of it as power dressing, but instead of being about power it is about pleasure, or power and pleasure, and I think there is a sense of community in that. It is about owning fashion’s “superficiality” but owning it for the right reasons.

A.F.: And finally, I would like to ask you a question on the writing process. Your tutor was Aya Noel, a journalist and former editor at 1Granary. How important was that collaboration? She gave you several writing tips that were really useful. What were they?

T.M.: That collaboration was really, really important to me. I wasn’t used to writing, and I have a lot of messy ideas that I have trouble putting together, so her tips were really about methodology and making me work the way I work with images. Instead of collecting images for a mood board, I assembled quotes and then thought of themes that related to my subject. I then cross-referenced all of this material to form final categories or chapters. For each quote, I asked myself why I thought they referred to my topic and how I would reword these quotes and understand them. By writing these bits, the text kind of wrote itself. I had read a lot of stuff and had a lot of material. Working through the material in this way allowed me to organise it and create threads. I went about my subject quite naively – or maybe just very literally. Reading texts and reacting to them in a straightforward manner really worked. It was really enjoyable to freely read some of the material and not be aware of the texts out there that say “this text says this.”

A.F.: How important would you say this work has been to your MA as a whole?

T.M.: I think it has been really quite important. It has helped me understand the importance of community in my work. It has also made me realise how difficult it is to translate theory into a design practice. The clothes will always seem more superficial than a text or a theory. It is very hard for clothes to say what a text is saying. But writing the thesis has helped me accept and own my design process better.

Back to summary

Back to summary