The Undiscussed University

Art practice and institutional transformation towards ecopedagogy

Text

“[T]he boundary between the universe of (orthodox or heterodox) discourse and the universe of doxa, in the twofold sense of what goes without saying and what cannot be said for lack of an available discourse, represents the dividing-line between the most radical form of misrecognition and the awakening of political consciousness.”1 (Pierre Bourdieu)

“Artistic practice and knowledge would no longer be confined to the studio and the gallery, but their field of activity would be extended to commercial, industrial and administrative contexts to act upon societal organisation and decision-making processes.”2 (Antony Hudek and Alex Sainsbury)

As an artist working in collaboration, my art practice activated reciprocal actions and responses in public contexts, while working in universities has paid my wages and supported my art practice with research grants. In 2012, to engage with the social-ecological crisis, I brought my art practice into the University of the Arts London (UAL) where I work. By making conceptual interventions, I encountered the separation of academic and artistic discourses and practices from the executive functions of the university. Elsewhere, I have reflected on how this separation enables capital accumulation, and the production of neoliberal subjectivities.3 Seeing the separation of discourses, practices and functions limit the potential to act and learn, I imagine them connected by the emancipatory influence of ecopedagogy.

In this essay, I refer to my earlier collaborative art practice as part of Cornford & Cross, and then describe a series of interventions I have made in UAL since 2012. To situate them, and interpret the responses, I draw on Pierre Bourdieu’s model of Doxa and Discourse, which articulates the relationship between the field of knowledge production and the power relations that bound it.

Cornford & Cross

From 1991-2014 I collaborated with Matthew Cornford as Cornford & Cross, making art projects that critically engaged with public contexts in relation to issues including militarism, economics, and ecological degradation.4 In aiming to generate productive forms of doubt around assumptions, concepts and definitions, this practice often confronted opposing viewpoints to generate “a crisis of incompatible elements and forces”.5

Cornford & Cross projects explored the terms and conditions of artistic engagement. “Like in a game in which the rules are written but the players’ moves are on the threshold of predictability, we advanced one step at a time.”6 However, the rules of the game itself were re-written when the Global Financial Crisis of 2007-8 was used in Britain as a pretext for the political programme of “austerity” and privatization which removed resources from public ownership and democratic oversight. Cuts to public funding for art galleries, commissions, residencies and publications erased many of the co-ordinates of professional artistic practice that I had relied on to facilitate the making of art. In this impoverished landscape, money became a source of contention, and Cornford & Cross ceased collaboration.

Artist Placement

In 2012, Raven Row Gallery in London exhibited the work of the Artist Placement Group (APG), and I was invited to facilitate a gallery discussion. Linking the APG themes of “placement”7 and “education,” and following Hayley Newman’s project, “Self-appointed artist-in-residence in the City of London”8, I designated my job at UAL as an artist’s placement, with a remit to engage with education in the social-ecological crisis. By suspending the distinction between my art and my work as an academic, I drew on the APG notion of “the open brief”9 to embark on a series of pedagogical experiments with no control.

As the marketisation of UK Higher Education was drawing universities into debt, UAL was embracing “the creative industries”, a reframing of artistic practice which aligned creativity with entrepreneurialism, and dispensed with criticality. At a Research Committee meeting, a marketing team presented UAL’s new branding, which centred on the slogan, “Because the world needs creativity”. I argued that UAL should explicitly commit to criticality as the corollary of creativity, because while creativity opens up new possibilities, criticality enables choices to be made between them on the basis of explicit criteria, enabling outcomes that are reflexive and emancipatory.10 I was told that the presentation was simply, “for information”, and the meeting moved on.

In 2013, UAL’s Vice Chancellor signed the People & Planet Green Education Declaration. As UAL had no democratic forum or channel for academics to communicate with the senior management and UAL Board of Governors, I wrote directly to the Vice Chancellor and his team, congratulating them on the declaration, but urging them to divest from fossil fuels. Although they didn’t reply, I wrote several more times, summarising and citing how the latest research had connected financial risk, fossil fuels and climate breakdown. I continued until the Head of Sustainability called me to a meeting, and ordered me to stop.

Following Pierre Bourdieu’s claim that “A truly critical form of thought should begin with a critique of the more or less unconscious economic and social bases of critical thought itself.”11, I made further interventions into the operating system of the university, including a proposal that UAL should switch to an ethical bank, and a student and staff campaign from 2012-2015 for UAL to divest from fossil fuels. Moving towards prefiguring a zero-carbon society, I also devised an educational project for sharing information and power between producers and consumers of renewable energy, and a proposal to remodel our university as a co-operative social enterprise. But in each case the proposals were ignored, dismissed or marginalized.12

Since then, I worked with colleagues to stage Climate Assemblies, explore Planetary Health, devise a “Carnival of Crisis” in response to COP26, and organise discussions on Climate Justice. I also contributed key parts of UAL’s Climate Action Plan. In all cases, I aimed to activate feedback loops between the artistic and academic activities of the university and its executive and operational functions.

Climate Assemblies

With extreme weather around the world attracting heightened media coverage, in late 2018, the Extinction Rebellion (XR) staged civil disobedience actions, moving the discourse from the continuity of ‘sustainability’ to the rupture of Emergency. XR issued the key demand that, “Governments must create and be led by the decisions of a Citizens’ Assembly on climate and ecological justice”.13 In May 2019, the UK Government declared a Climate Change Emergency.

At UAL, there was growing frustration at the Executive pursuit of business as usual, and students and staff welcomed the idea of a democratic forum to build consensus for action on the climate crisis. In Spring and Summer 2019, Margot Bannerman, Senior Lecturer in Fine Art, and Clare Farrell, founder member of XR, staged a series of XR climate assemblies, for students, staff and guests to learn about, and collectively respond to the climate and ecological emergency. I contributed to these assemblies, framing the discussion by citing Giorgio Agamben, who took examples from history to show that an emergency is a political State of Exception when the rule of law and fundamental rights are suspended, and power is delegated to the executive.14 Rather than cede the power to determine the nature and scope of actions to be taken, I said we should collectively develop a Climate and Ecological Action Plan for UAL’s curriculum and operations, and decide how to allocate the £3.9 million that UAL had pledged to divest from fossil fuels four years earlier.15

But my proposals went unnoticed, as the open discussion led to demands for more vegan meals in the canteen; recycling systems and bans of toxic materials in the workshops; an organic herb and dye garden; buying woodland to conserve biodiversity and offset carbon emissions; and carbon literacy training. I argued that we should clarify our aims, and agree a method to compare the ecological effects of different proposals, so we could focus our efforts. It was agreed to establish a set of Working Groups to develop proposals, and to demand that UAL convene an official Climate Assembly.

https://tinyurl.com/3tbxrs8f, last accessed on 17 September 2019

In September 2019, the UAL Press Team issued a story declaring, “UAL responds to the Climate Emergency”, announcing that Pro Vice-Chancellor Professor Jeremy Till would lead UAL’s response to the climate emergency. But it didn’t mention the XR climate assemblies.16

In October 2019, the Climate Assembly met, with official support from UAL through Jeremy Till, and superb facilitation from Kate Pelen. Presenting to the Assembly, I said, “Unlike a closed problem with known parameters, the social-ecological crisis is an open problem of divergent interests and conflicting subject positions.” I said we should recognise that our interactions were bounded by specific cultural formations and relations of power. As an example of how universities are bound up with the economic system driving the climate crisis, I showed the story by UAL [fig.1] and said, “UAL banks with the Royal Bank of Scotland, which has invested billions of pounds in extreme fossil fuel projects, including tar sands extraction from the land of first nation peoples in Canada, where the ancient forests are now burning.” I cited Nicholas Mirzoeff’s notion of the “Deep Contemporary” as the intersection of racism and the Earth system crisis,17 and I proposed that UAL’s Climate and Ecological Action Plan should combine decarbonization with decolonization to progress climate justice.

In January 2020, the official Climate Assembly met again. The evening before, as I was preparing to present on behalf of the Working Group on Divestment and Procurement, I received a phone call informing me that the Assembly could only go ahead on condition that fossil fuel divestment would not be discussed or negotiated. That night, I re-wrote my presentation to say that UAL needed a business model fit for purpose in the climate crisis, based on a Climate Action Plan to decarbonise within the Global Carbon.18 Noting that UAL’s income was over £320 million,19 I proposed that following the UK Government Committee on Climate Change,20 1%—2% of UAL’s added value should be invested annually to deliver such a Climate Action Plan.

Planetary Health: a ‘creative sanatorium’

When Covid-19 hit, the Climate Assemblies were suspended. With the university’s centralized and hierarchical systems, and its dependence on international jet travel exposed and vulnerable, students and staff shifted almost overnight to teach and learn online, adapting as a creative community by spontaneously sharing knowledge and skill, and collectively supporting an ethos of respect, trust and even friendship.

Following the UK government, UAL framed the pandemic as a discrete threat that necessitated delaying action on climate breakdown. I argued for viewing them as interconnected symptoms of the social-ecological crisis, “a dynamic situation of competing interpretations, conflicting interests, and unconscious impulses”, yet “which demands concerted action based on shared understanding”.21 With Gabrielė Grigorjevaitė I delivered a series of online workshops exploring Planetary Health through Art & Design.

Richard Horton and colleagues at the Lancet medical journal defined “Planetary Health” as, “The health of human civilisation and the natural systems on which it depends.”22 Planetary Health draws on work by the Stockholm Resilience Centre which identifies nine planetary boundaries in the Earth system.23 This model influenced the United Nations’ later recognition of the “fundamental intertwining of biodiversity and climate”.24 We read texts by authors including Gene Ray, who related the racialized aspects of the contemporary social-ecological crisis to the historical trauma of colonialism, and asked, “what a critical theory opened to Indigenous knowledge might begin to look like, at this decisive moment”.25

We framed the sessions as a “creative sanatorium”, a pedagogical experiment and a respite from productivity, competitive individualism, and from what I have termed “the orthodoxy of positivity”. Allowing uncertainty and doubt to coexist with intuition and playful digression, staff and students collectively inhabited the “negative” spaces of creative practice and research. Rather than aestheticize the crisis as a topic, we situated art practice-research as a social interaction aligned with the aims of Planetary Health: “understanding the dynamic and systemic relationships between global environmental changes, their effects on natural systems, and how changes to natural systems affect human health and wellbeing at multiple scales”.26

Climate Action: Net Zero v. Growth

In December 2020, members of the Climate and Ecological Action Group met James Purnell, the incoming President and Vice Chancellor of UAL, to demand urgent action on climate and biodiversity. He invited us to present to the UAL Executive Board, where I argued that achieving zero carbon emissions is essential, but not enough to avert climate collapse; the imperative is to stay within the Global Carbon Budget,27 by making early and deep cuts in fossil fuel use. I showed why UAL’s Climate Action Plan should use Science Based Targets, a method for decarbonising within the Planetary Boundaries, and align with the UN Sustainable Development Goals.28 By using Science Based Targets29, UAL’s Climate Action Plan could be proportionate to the scale and speed of climate breakdown, coherent with UAL’s values of anti-racism, and integrated with the new UAL mission of “social purpose”. I concluded that UAL was uniquely placed to achieve this through disruptive innovation and cultural transformation. Members of the Executive thanked me politely, and the meeting moved on.

Despite the quiet reception to my talk, the commitment that I had proposed: to achieve Net Zero within a just share of the Global Carbon Budget using Science Based Targets, was integrated into UAL’s Climate Action Plan.30 So I arranged for UAL to join the Environmental Association of Universities and Colleges (EAUC), and to accept their invitation for UAL to be a pilot institution developing a methodology for the UK Higher Education sector to use Science Based Targets.

Climate action, especially using Science Based Targets, requires a sense of size and proportion based on measurement and categorization. Organizations’ carbon emissions are categorized into Scopes 1, 2 and 3,31 with Scope 3 emissions often the largest by far. I had long argued that UAL could learn through Action Research to reduce its total carbon emissions, and in July 2023, Niamh Tuft, UAL’s Climate Action Manager, asked me to write a business case for calculating UAL’s Scope 3 emissions. UAL’s Carbon Management Plan declared its Scope 3 emissions as 93% of the total, at 99,600 tonnes.32 But this figure excluded, without explanation, around 400,000 tonnes of Scope 3 emissions from UAL’s construction projects.

Moreover, UAL’s 2021-22 Annual Report only refers to Scope 1 & 2 emissions of 5,400 tonnes, and “saving 324 tonnes of carbon from energy management projects”.33

The business case I wrote, and my work with EAUC, were paused until the arrival of UAL’s new Chief Social Purpose Officer, Polly Mackenzie, who took responsibility for Scope 3 emissions. At the time of writing, the calculation of UAL’s Scope 3 emissions is on hold, perhaps to be outsourced to a commercial consultant, while four new posts have been created on the Social Purpose communications team.

With a stated aim to achieve Net Zero emissions, UAL plans to double the number of learners on UAL courses.34 Having delayed the calculation of emissions, the plan is to grow and wait until 2030 to “consider approaches to carbon offsetting”.35 UAL’s Audit Committee is said to monitor risk management, but the list of key risks affecting the university does not include climate breakdown.36 I alerted the Chief Social Purpose Officer to UAL’s lack of climate risk management, warning that it is a high risk to assume it is still possible to avert uncontrollable climate breakdown. I also sent her research showing that offsetting is scientifically flawed, and socially unjust, as it delays climate mitigation and adaptation, increasing the burden and shifting it onto poor and vulnerable people in the Majority World, and onto future generations.37 But it is unclear whether UAL’s plan will change as a result.

Climate Justice: Decolonising Decarbonisation

In 2022, Rahul Patel and I organised a series of discussions on Climate Justice, connecting resistance to climate breakdown with opposition to structural racism and the legacy of colonialism.38 Speakers included teaching and research staff, students, a Pro Vice Chancellor of UAL, trade unionists, and artists, designers and activists.

A key tenet of climate justice is that climate breakdown hits hardest and soonest the most vulnerable and marginalized people who caused the least damage and are least equipped to cope with the destruction. What is rarely discussed is that the reason why whole regions and societies are ill-equipped is because they have been systematically dispossessed by centuries of colonialism,39 and decades of globalisation.40 While “the legacy of historical trauma remains largely unacknowledged or misrecognized by the people who have inherited its benefits”41 injustice is compounded with deception, as global corporations use the transition to renewable energy to greenwash neocolonial expansion of mineral extraction.42

A key parameter for climate justice is the Global Carbon Budget, the limit to how much carbon can be emitted without triggering climate collapse. This is the crucial link between decarbonisation and decolonisation, because it opens the question of who has the right to emit carbon, and so extends the issue from technical calculation to ethical judgment.

The weighing of evidence and the balancing of competing claims is symbolised by the Scales of Justice. But justice must be based on legitimacy. For climate justice to be legitimate, the procedures for making decisions— on sharing the Global Carbon Budget, on debt relief, and on compensation for climate loss and damage— must be transparent, equitable, and inclusive of the views of marginalized peoples.

From Carbon Literacy to Climate Fear

Following the Climate Assemblies’ call for curriculum and staff development around the climate crisis, UAL funded a Carbon Literacy training scheme, developed by Margot Bannerman and accredited in 2023.43 UAL Staff Development Officer George Barker drew on work by Margot Bannerman to develop a set of interactive ‘webinars’ for staff and students. I took part in the pilot sessions and gave feedback advocating a critical engagement with carbon literacy as a contested field. I said that fossil fuel and mineral corporations, their financiers and the private media obscure the historical origins of the climate crisis, and emphasise technocratic, market-oriented and individualist solutions.44 I showed that the personal carbon footprint was devised by a public relations firm to deflect public attention away from the oil company that caused the Deepwater Horizon catastrophe,45 and whose CEO was later pivotal in the withdrawal of funding for Higher Education in the UK.46

Carbon literacy shares with financial literacy a tendency to mask social harm within an ostensibly neutral discourse. Max Haiven has critiqued financial literacy programmes aimed at Indigenous peoples in the land now known as Canada. Referring to “The Uses of Literacy” (1957) by Richard Hoggart, Haiven argues that financial literacy programmes produce “a profound financial illiteracy by obfuscating the systemic and structural dimensions of debt, financial hardship, and the patterns of financialization, thus reaffirming a neoliberal trend to privatize social problems”.47

George Barker later worked with UAL Creative Producers Maite Pastor Blanco and Laurane Le Goff on “Facing Climate Fears”, a staff development programme which invites people to share their anxieties around the climate and ecological crisis. I went along, ready to discuss climate anxiety in the learning environment. Outlining my work over 10 years to persuade UAL to engage with the climate crisis, I said the UN had recently warned that business as usual will lead to 2.8˚C of heating.48 This far exceeds the Earth system tipping points,49 probably precipitating cascading systemic impacts including the mass extinction of species and worldwide societal collapse.50 I talked about research showing that the poorest and most vulnerable people will disproportionately suffer and die. Picturing the vast, growing gap between our university’s narrative and its actions to tackle the climate crisis, I was overcome with emotion, and I wept.

The Universe of the Undiscussed

The campaign for UAL to divest from fossil fuels, which I initiated and co-led, was eventually met by an official pledge to divest £3.9 million, but our campaign was never acknowledged, and despite repeated written requests, no evidence of divestment was ever provided. My calls for the academic and executive functions of UAL to work together in responding to the climate and ecological crisis were ignored, and my bids to model UAL as a social enterprise, and to visualise energy consumption were blocked. My proposal in 2014 that UAL should switch to an ethical bank was rejected as impractical, though in 2022 UAL did switch from NatWest (formerly RBS) to Lloyds bank. In no case was a sufficient explanation given.

Since the Climate Assemblies of 2018-20, the UAL Press Team has issued a flow of positive stories about climate action, deflecting attention away from the university business model and operations by focusing on the curriculum, and creative student work. The UAL Climate Action Plan developed this approach, by juxtaposing provoking images and radical declarations with commitments to the key parameters of climate action, but without citing the relevant research, or setting out plans for actual decarbonisation. The lack of climate risk assessment in the university’s governance or strategy signals a disconnection from scientific evidence,51 from international policy,52 from public perceptions,53 from financial institutions54 and from UAL’s own Climate Action Plan, which pledges to “change the way we operate”.55

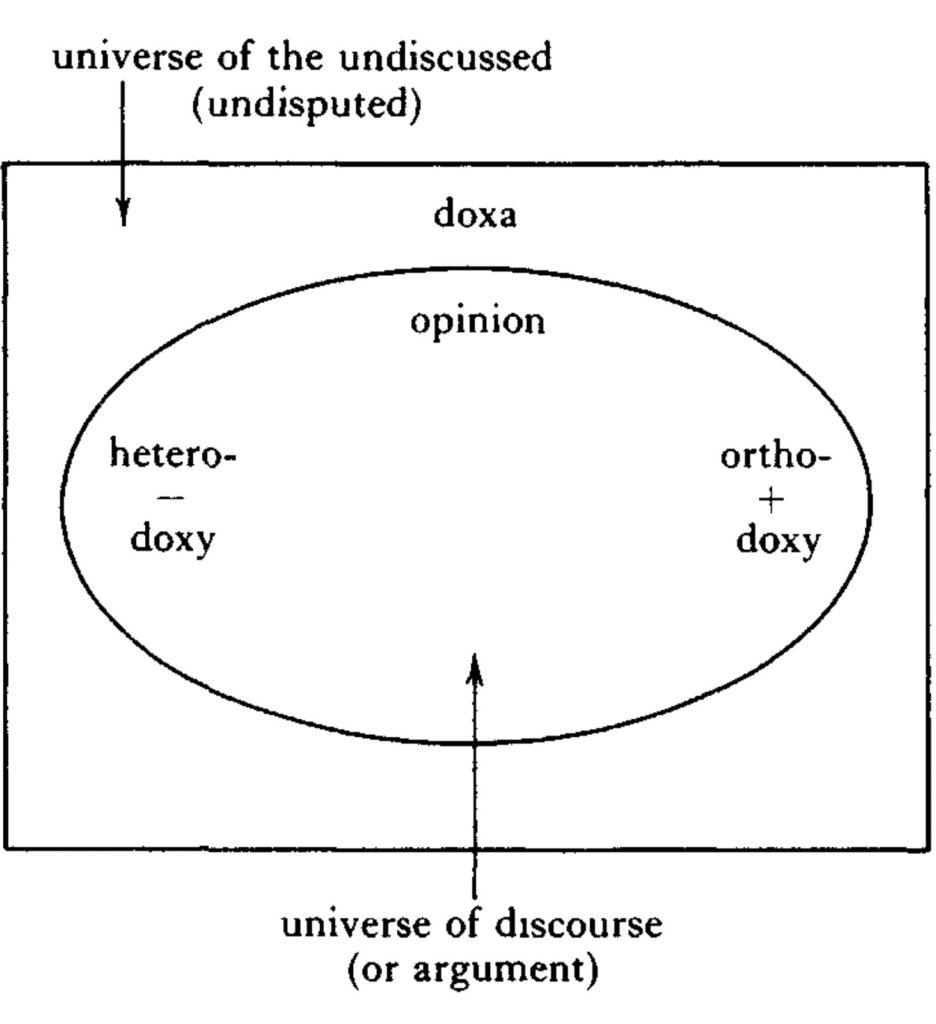

In his analysis of the relationship between knowledge and power, Pierre Bourdieu developed the model of “doxa”, to theorize the tendency of social groups to produce a sense of limits and classifications that define a shared idea of reality:

“Systems of classification which reproduce, in their own specific logic, the objective classes, i.e. the divisions by sex, age, or position in the relations of production, make their specific contribution to the reproduction of the power relations of which they are the product, by securing the misrecognition, and hence the recognition, of the arbitrariness on which they are based […] This experience we shall call doxa, so as to distinguish it from an orthodox or heterodox belief implying awareness and recognition of the possibility of different or antagonistic beliefs.”56

In a schematic diagram [fig. 4], Bourdieu situates the “universe of discourse” which includes both “heterodox” and “orthodox” opinions, within the doxa, the universe of the undiscussed.

In the university, the tacit acceptance by academics of the boundary between what may and may not be discussed is inexplicable within the terms of a critical discourse, but inevitable under the executive control of budgets, salaries, workloads, and academic career progression. With its business model and operations in the “universe of the undiscussed”, the UAL executive influences the “universe of discourse” by selectively moving issues from the heterodox to the orthodox area of discussion, in the process reframing them to serve the existing order. The executive and operational functions of the university are thus empowered to recuperate the critical labour of staff and students, while remaining exempt from academic critique, signalling that business can influence academic enquiry, but academic enquiry cannot influence business. If, “[d]oxa, as a symbolic form of power, requires that those subjected to it do not question its legitimacy or the legitimacy of those who exert it”57 then it is incompatible with critical pedagogy and climate justice.

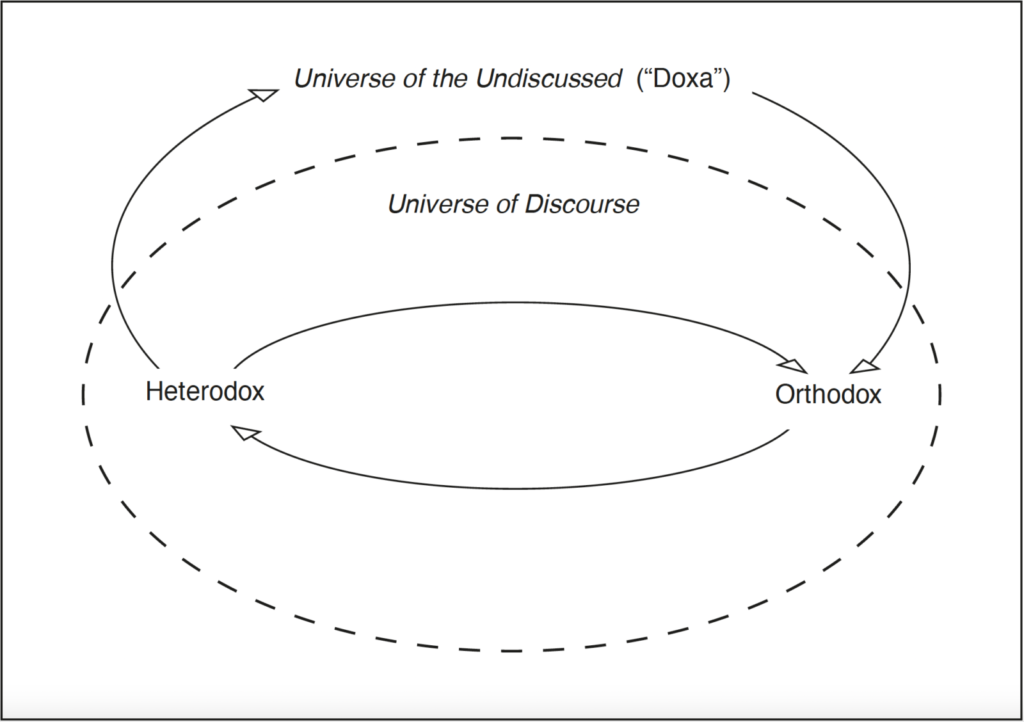

Yet the interventions described here, and the executive responses to them, have revealed the limit to accepted discourse. Furthermore, despite encountering obstructions, disconnections and gaps, these interventions have contributed to the transformation of the official mission, strategy and policy of the university, suggesting that the boundary of the doxa is neither fixed nor impermeable.

Having engaged with the movement from “heterodox” to “orthodox” opinions, and between the “universe of the undiscussed” and the “universe of discourse”, I redrew Bourdieu’s diagram to visualize a process of elliptical exchanges across a semi-permeable boundary:

Conclusion

Through its mission of Social Purpose, UAL aims to achieve Net Zero carbon emissions while planning to double student numbers. That the conflict between these goals is undiscussed is symptomatic of the structural separation between the university’s academic activities and its business operations. With “no credible pathway” for nations to limit global warming to 1.5˚C58 the university must develop “post carbon transnationalism” by charting a credible pathway to minimise and delay climate collapse, while also preparing staff and students for a world of uninsurable risks.59 Yet having constrained and marginalized critique, the university has weakened the reflexive skills and emancipatory tendencies needed to address the social-ecological crisis in which it is implicated.

However, “Crisis is a necessary condition for a questioning of doxa but is not in itself a sufficient condition for the production of a critical discourse”.60 A discourse cannot be recognized as such until it is brought into relation with another discourse; as Roslyn Frank observes, “only when we are confronted with a different conceptual horizon, as expressed by a (radically) different culture and language, can we begin to reflect back on our own”.61 A critical discourse can develop such reflection, by questioning how certain concepts and patterns of thought and communication serve particular relations of power.

The university’s power combines economic, cultural and social capital,62 which are articulated through the separation of its academic and executive communities. UAL builds cultural and social capital in its “universe of discourse” by facilitating and publicly celebrating the work of its students and staff. Meanwhile, UAL builds economic capital, complying with regulatory requirements for reporting in its financial statements, but positioning its governance, strategy, risk management and operations in the “universe of the undiscussed”. This has a dual effect: it exempts the business model and executive functions from intellectual critique, and it sets a “hidden curriculum”,63 which in this context teaches that creative and critical practices are subject to a legal and policy environment designed to favour private interests in a growth-based, and therefore ecocidal, economy. As such, the boundary between these universes is a key site of “[…] the struggle for the power to impose the legitimate mode of thought and expression that is unceasingly waged in the field of the production of symbolic goods”.64

In a more diplomatic mode, UNESCO describes a “Whole Institution Approach” to education for sustainable development: “ESD is not only about teaching sustainable development […] the educational institution as a whole has to be transformed. […] In this way, the institution itself functions as a role model for the learners”.65 But while the premise is sound, the conclusion presupposes that the institution and the learners are different groups, interacting according to the liberal ideal of formal equality. In the actual context of economic inequality, and its value system of social domination, the will to make a just transformation is inversely proportionate to the ability to make it: the executive has the strongest incentive to distance itself from the learners by maintaining the universe of the undiscussed.

One way past this impasse is for executive staff to identify themselves as learners, and to acquire the cross-cutting competencies that UNESCO says are crucial for all learners to advance sustainable development. These competencies include “the abilities to recognize and understand relationships […], to apply the precautionary principle […], to deal with risks and changes […], to understand and reflect on the norms and values that underlie one’s actions […], to learn from others […], to reflect on one’s own values, perceptions and actions […], to deal with one’s feelings and desires […], to apply different problem-solving frameworks to complex sustainability problems, and develop viable, inclusive and equitable solution options”.66

Acquiring these competencies could foster a rapprochement between the university’s executive functions and the discourses and practices of its academic and artistic community, easing the move from a paradigm of control to one of agile responsiveness to complex, non-linear interactions between social and ecological systems.

Designating an academic job as an artist placement mobilised a critical impulse between the universe of discourse and the universe of the undiscussed. This transgression has provoked defensive reactions including obstruction and feigned indifference, but it has also activated exchanges that have helped transform the university’s self-image and discourse. The task now is to activate a feedback loop between symbolic gestures and concrete changes, ensuring they escape recuperation as marketing stories.

Notes

- Pierre Bourdieu, Outline of a Theory of Practice, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977, p. 168.

- Antony Hudek and Alex Sainsbury, Context if Half the Work: A Partial History of the Artist Placement Group, Berlin: Kunstraum Kreuzberg/Bethanien, 2015, p. 2.

- David Cross, “Never Let Me Go”, in David Blamey and Brad Haylock (ed.), Distributed, London: Open Editions, 2018, pp. 29—51.

- John Roberts and Rachel Withers, Cornford & Cross, London: Black Dog, 2009.

- David Cross, “A Placement for Everyone”, in Marie Sierra and Kit Wise (ed.), Transformative Pedagogies and the Environment, Champaign: Common Ground, 2018, pp. 33.

- David Cross, “Mobilising Uncertainty”, in Elizabeth Fisher and Rebecca Fortnum (ed.), On Not Knowing: how artists think, London: Black Dog, 2013, p. 32.

- (Ed.) Between the mid-1960s and 1980s, the Artist Placement Group organised ‘placements’ for artists in companies or public institutions, with the idea of achieving mutual benefit through artistic work closely linked to the context.

- Hayley Newman, “About”, 2011, available at https://www.hayleynewman.org/about (last accessed on 3 March 2023).

- (Ed.) A kind of carte blanche given to the artists so that the results of their practices remain open and are conceived during the exchange process. Antony Hudek and Alex Sainsbury, op. cit., p. 3.

- Raymond Geuss, The Idea of a Critical Theory: Habermas and the Frankfurt School, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981.

- Pierre Bourdieu and Hans Haacke, Free Exchange, Cambridge: Polity Press, 1995, p. 74.

- David Cross, “A Placement for Everyone”, op. cit.

- Extinction Rebellion, “Our Demands”, 2018, available at https://rebellion.global (last accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Giorgio Agamben, State of Exception, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005.

- Emma Howard, “Ten UK universities divest from fossil fuels”, The Guardian, 10 November 2015, available at https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/nov/10/ten-uk-universities-divest-from-fossil-fuels (last accessed on 3 March 2023).

- UAL Press Team, September 2019, available at https://www.arts.ac.uk/about-ual/press-office/stories/university-of-the-arts-london-responds-to-climate-emergency (last accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Nicholas Mirzoeff, “Devisualizing the Deep Contemporary” [talk], Art and Decolonization Symposium, London: Afterall and Museu de arte de São Paulo (MASP), May 2019.

- Bård Lahn, “A history of the global carbon budget”, WIREs Climate Change, vol. 11, no. 3, 2020.

- UAL, Annual Report and Financial Statements, July 2019, available at https://www.arts.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0024/193155/UAL-_FS_2019.pdf (last accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Committee on Climate Change, Net Zero: The UK’s contribution to stopping global warming, London: Committee on Climate Change, 2019.

- David Cross, Get Well Soon: Planetary Health and Cultural Practices, London: Social Design Institute, October 2020, p. 2, available at https://www.arts.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/259100/SDI_Cross_3.2_ed.pdf (last accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Richard Horton, Robert Beaglehole et al., “From public to planetary health: a manifesto”, The Lancet, vol. 383, no. 9920, 2014, p.847.

- Johan Rockström et al., “Planetary boundaries: exploring the safe operating space for humanity”, Ecology and Society, vol. 14, no. 2, 2009.

- Hans-Otto Pörtner, Robert Scholes, et al., Workshop report on biodiversity and climate change, Bonn; Bremen; Geneva: IBPES and IPCC, 2021.

- Gene Ray, “Writing the Ecocide-Genocide Knot: Indigenous Knowledge and Critical Theory in the Endgame”, South as a State of Mind #9 [documenta 14 #4], no. 9, 2017, p. 121.

- Montira J. Pongsiri, et al., “Planetary health: from concept to decisive action”, The Lancet Planetary Health, vol. 3, no. 10, October 2019, available at https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanplh/article/PIIS2542-51961930190-1/fulltext (last accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Bård Lahn, op. cit.

- Science Based Targets initiative, February 2023, available at https://sciencebasedtargets.org (last accessed on 3 March 2023).

- (Ed.) An initiative aimed at businesses, seeking to turn their transition to a low-carbon economy into a competitive advantage.

- UAL, Climate Action Plan, 2023, available at https://www.arts.ac.uk/about-ual/climate-action-plan (last accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Greenhouse Gas Protocol, Corporate Value Chain (Scope 3) Standard, 2011, available at https://ghgprotocol.org/standards/scope-3-standard (last accessed on 3 March 2023).

- UAL, Carbon Management Plan – realising a net-zero carbon institution by 2040, June 2023, p. 6; 19; 24 available at https://www.arts.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0021/213852/UAL-CMP-v1272.pdf (last accessed on 3 March 2023).

- UAL, Annual Report and Financial Statements, July 2022, p. 45, available at https://www.arts.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0021/376131/UAL-Report-and-Financial-Statements-31-July-2022.pdf (last accessed on 3 March 2023).

- UAL, Our Strategy, 2022, p. 7, available at https://www.arts.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0036/339984/UAL-our-strategy-2022-2032.pdf(last accessed on 3 March 2023).

- UAL, Annual Report and Financial Statements, July 2022, p. 45, op. cit.

- Ibid., p. 58.

- Wim Carton, Jens Friis Lund and Kate Dooley, “Undoing Equivalence: Rethinking Carbon Accounting for Just Carbon Removal”, Frontiers in Climate, vol. 3, art. 664130, 2021.

- David Cross, “Climate Justice: Decolonizing Decarbonization”, Council for Higher Education in Art and Design, 2022, available at https://www.chead.ac.uk/climate-justice/ (last accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Walter Rodney, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, London/New York: Verso, 2018 [1988].

- Fouad Makki, “The empire of capital and the remaking of centre-periphery relations”, Third World Quarterly, vol. 25, no. 1, 2004, p. 149–168.

- David Cross, “Decarbonisation and Decolonization: Liberation?”, in Kieren Jones (ed.), Material Futures: where science, technology and design collide, London: Central Saint Martins, 2019, p. 94-96, available at https://issuu.com/csmtime/docs/ma_material_futures_catalogue/52(last accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Benjamin Hitchcock Auciello, A Just(ice) Transition is a Post-Extractive Transition, London: London Mining Network and War on Want, 2019.

- Carbon Literacy Project, 2023, available at https://carbonliteracy.com (last accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Michael E. Mann, The New Climate War, New York: Public Affairs, 2021.

- Mark Kaufman, “The Carbon Footprint Sham”, Mashable, July 2020, available at https://in.mashable.com/science/15520/the-carbon-footprint-sham (last accessed on 3 March 2023).

- David Cross, “A Placement for Everyone”, op. cit.

- Max Haiven, “The Uses of Financial Literacy: Financialization, the Radical Imagination, and the Unpayable Debts of Settler Colonialism”, Cultural Politics, vol. 13, no. 3, 2017, p. 348.

- UN Environment Programme, Emissions Gap Report: The Closing Window – Climate crisis calls for rapid transformation of societies, Nairobi: United Nations, 2022.

- David I. Armstrong McKay, et al., “Exceeding 1.5°C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points”, Science, vol. 377, no. 6611, 2022.

- Luke Kemp, et al., “Climate Endgame: Exploring catastrophic climate change scenarios”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 119, no. 34, 2022.

- Brian O’Neill, Maarten van Aalst and Zelina Zaiton Ibrahim, “Key Risks Across Sectors and Regions”, in UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Working Group II, Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, Cambridge, UK and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2022, available at https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGII_Chapter16.pdf(last accessed on 3 March 2023).

- UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, Our World at Risk: transforming governance for a resilient future, 2022, available at https://www.undrr.org/gar2022-our-world-risk#container-downloads (last accessed on 3 March 2023).

- AXA Insurance, Axa Future Risks Report, 2022, available at https://www.axa.com/en/news/2022-future-risks-report (last accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Patrick Bolton, et al., The Green Swan: Central banking and financial stability in the age of climate change, Basel: Bank for International Settlements, 2020.

- UAL, Climate Action Plan, op. cit.

- Pierre Bourdieu, op. cit., p. 164.

- Cécile Deer, “Doxa”, in Michael Grenfell (ed.), Bourdieu Key Concepts, Abingdon: Routledge, 2013, p. 116.

- UN Environment Programme, op. cit.

- Patrick Bolton, et al., op. cit., p. 24.

- Pierre Bourdieu, op. cit., p. 169.

- Roslyn M. Frank, “Shifting Identities: The Metaphorics of Nature-Culture Dualism in Western and Basque Models of Self”, Metaphorik, April 2003, p. 74.

- Pierre Bourdieu, “The Forms of Capital” [1986], in Imre Szeman and Timothy Kaposy (ed.), Cultural Theory: An Anthology, Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011, p. 81-93.

- Henry A. Giroux, “Developing Educational Programs: Overcoming the Hidden Curriculum”, The Clearing House, vol. 52, no. 4, 1978, p. 148-151.

- Pierre Bourdieu, Outline of a Theory of Practice, op. cit., p. 170.

- UNESCO, Education for Sustainable Development, Paris: UNESCO, 2017, p. 53.

- Ibid., p. 10.

Back to summary

Back to summary