The Long History of Trans Identities

Building trans archives, historicizing gender

Abstract

We have heard enough from the people who complain about an “epidemic of transgenders.” This harmful termcompares being trans with a contagious illness and ignores an entire swath of history. The controversies provoked by such expressions reveal, through their omissions, that we know nothing, or almost nothing, about trans existence prior to the very recent past. It has been made invisible. The search for the traces of those who have lived in the margins, beyond or outside of the gender norms of their time, is an essential undertaking not only for trans people, but also for the historicization of normative gender and sexuality, notably the woman/man binary, in the interest of reconsidering their presumed naturalness. Let us dive into the heart of the Middle Ages, in search of those who have long been experimenting with gender.

Text

“— So, kiss me! Says the queen.

Silence gives her a chaste kiss on the forehead, above the wimple, because, honestly, he does not fancy the kind of kiss she desires. And the lady, who does not wish to be so parsimoniously embraced, gives him five soft kisses, loving and languorous, in addition to the two she had promised. She overwhelms him with so many that Silence is quite embarrassed.”1

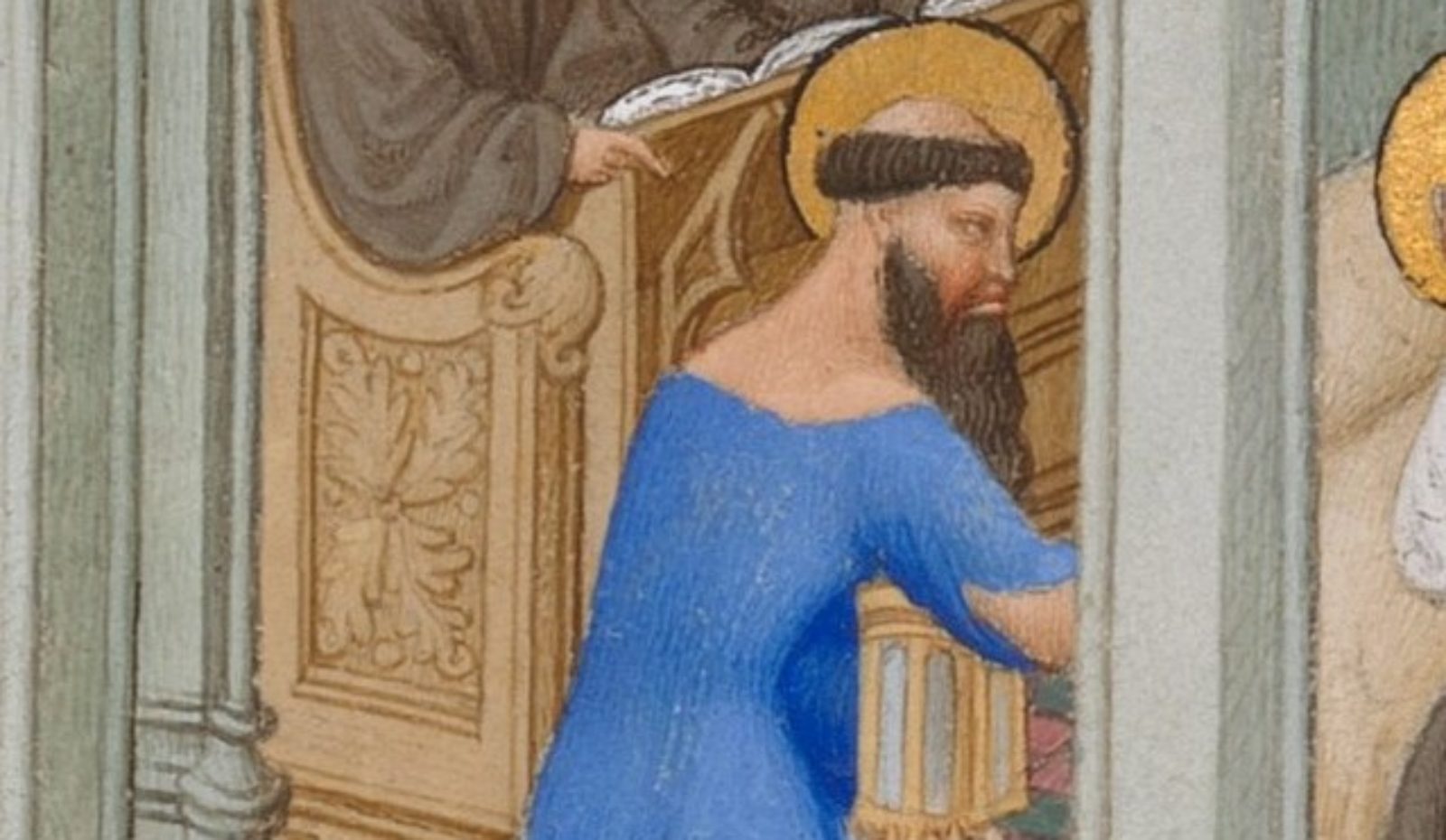

This love game between an adulterous queen and a knight of the court of Cornwall in the 13th century is not as “cisheteronormative” as we might think. The Romance of Silence stages the sovereign Eufème, who, married to the king, has taken a transgender nun as a lover, and has fallen in love with a knight, named Silence, who is also transgender.2 The latter’s parents gendered him masculine from birth in order to ensure that he would receive his inheritance, and he led a career first as a troubadour, then as a knight. The nun conceals her love life with the queen under her habit. At the end of the story, the prophet Merlin reveals the gender assigned to Silence at birth, as well as that of the woman who has been passing herself off as a nun. The queen, judged too enthusiastic in her sexuality, is sentenced to death, while Silence becomes a woman and marries the king.

It thus becomes clear that some of the heroes and heroines of chivalric romances that fed a binary heterosexual imaginary in the 19th century were not always what this prudish century made them out to be. Tristan sometimes wears damsels’ dresses in order to meet with Yseult; Silence swaps genders as his adventures unfold; God physically transforms Yde upon blessing his love with the young Olive, as Yde was originally dressed as a man to escape a forced incestuous marriage his father attempted to impose on him.

The presence of gender transitions in some chivalric romances should not be so surprising.

The presence of gender transitions in certain chivalric romances should not be so surprising. In light of trans studies and trans people coming out in the media, the general public has become conscious that trans people are everywhere, and perhaps always have been, in all social strata. Depending on the period, people who did not conform to the gender norms of the time were referred to in various ways (in the 12th and 13thcenturies it was said that “a woman made herself into a man” or “this man is a woman”), and the discriminations they suffered were not evenly distributed: for example, medieval society controlled sexuality (legitimate or illegitimate) more stringently than gender norms. Without claiming that experiences across the centuries are necessarily comparable, it is time to shed new light on the long history of trans identities.

Visibility and Invisibility

Some recent advances in trans rights, such as the right to legally change one’s name and gender marker without having undergone medical or surgical intervention, have come at the price of increased visibility. This has been followed by backlash, including shameless bigotry; meanwhile, transphobic individuals have found media and political platforms,3 claiming that trans issues are pathologies that only affect a small minority of the population. They thus oppose historical and sociological work, which testifies to their ignorance, and often publish their arguments in poorly informed, even blatantly false texts that fret over an “anthropological upheaval,” bemoaning the danger of undermining what they claim to be biological constants, such as the man/woman binary. Previously, throughout the 20th century, doctors published about “transvestites” and “transsexuals” (people who we would now call “trans women” but who doctors tended to describe in the masculine), presenting them as dangerous or pitiful.4 The pseudo-feminist anti-trans arguments currently echoed in France have their origins in the 1979 worries of a woman trained in theology, named Janice Raymond, who was upset about the presence of “transsexuals” in feminist movements. In 1991, the feminist, lesbian, transgender musician Sandy Stone published “The empire strikes back, a post-transsexual manifesto” in response to Raymond’s denigration, as well as to harassment she had personally suffered.5

Trans studies and trans knowledge have been built through a reappropriation of expertise.

Trans studies and trans knowledge have been built through a reappropriation of expertise. Trans people and allies have developed a flourishing body of literature that has notably allowed for the publication of a quadrannual scientific journal, Transgender Studies Quarterly, and the creation, in France, of the Observatory of Trans Identities (l’Observatoire des transidentités) by Karine Espineira and Maud-Yeuse Thomas.6 At the impetus of researchers like Susan Stryker, the history of “trans liberation” has emerged, alongside long-standing, non-Western histories of trans identities and transness (being trans).7 In the 1990s, Leslie Feinberg had opened a path by studying non-Western visions of gender since Joan of Arc.8 In this vein, we will examine so-called premodern societies, in which nature and culture were not defined as they are today and in which the boundary between sex and gender was not conceived in the same terms. What could we learn from the meagre clues that reach us from such distant societies? Can we know something about the histories of people who are nearly invisible in the record?

In search of the subject

Contemporary discourse privileges direct testimony, but in historical sources we find few stories told in the first person. We have access to the diary, albeit heavily modified by her publishers, of the Danish artist Lili Elbe, who requested a medical transition in the 1930s.9 In the United States, there are some testimonies of gender changes from people who escaped from slavery, notably the famous Harriet Jacobs, who in her 1861 autobiography recounts passing as a sailor by darkening her skin with charcoal in order to escape.10 Almost a century earlier, several letters penned by the Chevalière d’Éon make reference to social gender transition: after passing as a woman in order to work as a spy, d’Éon later wishes to return to France as a man. Perceived as a woman dressed as a man, in 1777 d’Éon is ordered by the king to wear women’s clothing. D’Éon kept their gender assigned at birth a secret their entire life.11 From an even earlier period, we have the police statement of Eleanor Rykener, arrested in London in 1395.12 Rykener explains that, for example, according to her deposition, she goes by Eleanor when she has relations with priests, but calls herself John and behaves as a man in order to sleep with nuns. Note that in London in 1355, even if “prostitution” was not forbidden, “sodomy” – defined as nonconforming sexuality, especially between people of the same gender – was prosecuted. We don’t know the outcome of Rykener’s arrest, but we can conclude that her goal was to render her sexual practices tolerable in the legal context of her time. This small collection of documents, although traces of specific sociopolitical contexts, coming from eclectic periods and places, were nonetheless all generated in periods that were hostile to gender nonconformity, and testify to the will of their authors to make their situations liveable, documenting the strategies that they employed to avoid moral and legal condemnation.

In 1395, Rykener explains that she goes by Eleanor when she has relations with priests, but calls herself John and behaves as a man in order to sleep with nuns.

The quest for first-person testimony continues; perhaps new sources will come to light in the near future. Their interpretation will always be open to question: the fact that there does not exist a single term to designate these people demonstrates that the question reappears periodically without necessarily being pinned down or uniformized by a definition. For example, in the 19th century, the “crime of cross-dressing” describes people who don’t dress according to their sex, but this expression did not exist in the Middle Ages. Officially, during the latter period, a woman could not wear men’s clothing, nor could a man wear women’s clothing, but there were many exceptions that made this acceptable – for example, to protect oneself during a voyage, to preserve one’s moral virtue, or in the name of asceticism – as the writings of Thomas Aquinas testify. There is thus no one medieval record of this type of infraction, and we most frequently discover them in judicialarchives, generally in the category of sexual crimes.

Let’s examine another example. In Venice, in the 14th century, the Lords of the Night (Signori di notte) investigated crimes. In 1355, they arrested a person who everyone knew as Rolandina Ronchaia, but who they call Rolandinus, in the masculine.13 We have no traces of what Rolandina thought, but the magistrates’ detailed investigation shows that she seems to have been harassed on the Rialto bridge while trying to prove that she was in fact a man, even though she passed as a woman, and her sexual relations with men thus fell under the accusation of illicit sexuality, or “sodomy.” The fact that her acts were repeated eventually led to her death sentence. Justice of the time was particularly violent; sexual crimes had become a priority for the Republic of Venice, who believed that the degradation of morals was the cause of the Black Death of 1348.

In the most famous medieval trial, that of Joan of Arc in 1431 in Rouen, we find information about Joan’s masculine dress. We understand that she wore these garments just as much on the battlefield as in daily life, ever since she had procured them in Lorraine. But Joan did not pass for anything other than a young girl (“pucelle,” or “virgin,” which signified “unmarried,” was the nickname she gave herself). The words recorded in a trial of this kind tell little about her intentions: the sentence of the condemnation was worse than death, as being burned at the stake for heresy denied her eternal Christian life.

“Interrogated on why she had begun to wear men’s clothing in this way, [Joan of Arc] responded that it was of her own free will, with no obligation, and that this dress pleased her more than that of a woman.”14

The testimony of real people speaking in the first person is heavily influenced by context, as they were often caught up in judicial proceedings at the time of writing. We often stumble across these documents unexpectedly as we dig through various sources, and the project of writing a history of trans people is thus complicated by the impossibility of tracing a continuity across these disparate records. However, they nonetheless point to multiple ways of transcending both gender norms and surviving repression. In addition to first-person historical testimony, there is the world of literary and hagiographic sources, in which ideal versions of gender transcendence can appear.

The question of trans sainthood

How could a notion of trans sainthood have developed? This term has recently emerged through the cataloguing of some thirty cases in Christian hagiography of saints who, initially gendered feminine, passed as masculine for part of all of their lives. Some of these stories had been known to historians since the 1950s, but the way in which they are read has changed considerably, and these cases are now being closely studied. Feminist historians, such as Marie Delcourt in the 1950s and Évelyne Patlagean some twenty years later, spoke early of feminine power linked to mythological figures (the “Diana Complex”),15 or of forms of emancipation from gender norms16 in relation to these characters. Subsequent generations of historians referred to them with the exogenous term “cross-dressing saints.” A debate then occupied the historical field regarding whether these “saints” were really women (or eunuchs or transgender men), but also regarding whether the tales that so enthralled medieval Christians were purely literary, or possibly also historical.17

Many such cases date from the 2nd and 3rd centuries and take place in ascetic communities. Before Christianity officially became the religion of the Roman Empire in 391-392 (it had been tolerated since 313), a few fervent converts had rejected the roles associated with their genders: they cut their hair, dressed in masculine clothes, and refused the marriages arranged by their parents. Saint Thecla, a disciple of Paul of Tarsus whose story is told in the Acts of Paul and Thecla, is particularly memorable. According to this account, Thecla refused marriage, was baptized, and was authorized by Paul to preach in masculine dress. Thecla died a martyr, becoming the first “woman” to die for Christianity (in men’s clothing). However, the text was excluded from the corpus of the Acts of the Apostles and declared apocryphal by the Fathers of the Church, resulting in the loss of certain fragments. Her worship is nonetheless well-documented throughout the Middle Ages and up through today in certain regions, notably amongst women who gathered in the Hagía Tékla cave in Silifke, Turkey.18

In the 4th century, we find some converts who reject the roles associated with their genders: they cut their hair, dress in men’s clothing, and refuse marriage.

While men in Roman patrilineal society were regaining power over the bishops and religion, these “women” who left their husbands and passed as men were condemned in a church Council at Gangres (today Çankırı, Turkey) around 340. “Women” were forbidden from cutting their hair, which had been given to them to“remind them of their dependence” (canon 17 of the Council), from wearing men’s clothing (canon 13), from abandoning their husbands (canon 14), and from abandoning their children (canon 15). The need to instate such measures testifies to the fact that these events occurred too frequently in the eyes of the Council’s bishops. Jerome of Stridon, who translated the Bible into Latin (the Vulgate) and was surrounded by many devout women, himself complained about those who “cut their hair and, without modesty, donned the face of a eunuch.”19 The ascetics who we would call transgender today often passed as eunuchs, because in the Byzantine Empire masculinity was characterized by beards, and men without beards were necessarily perceived as eunuchs, a “third gender” that long persisted in the Empire.20 Their worship and their stories inspired hagiographic narratives – the lives of saints – from the 5th century onwards.

In Rome, the case of Saint Eugenia, also known as Brother Eugene, is particularly revealing. The story goes that the young girl passed as a eunuch alongside two of her companions, Protus and Hyacinth, themselves also eunuchs. The three join a Christian community in which the brother, now called Eugene, becomes an abbot and healer. Falsely accused of sexual assault by a jealous woman, he is brought to court before his own father, the Prefect Philip, who recognizes his child. The father, Eugene, and even the mother become proselytizing Christians and die in Rome during a persecution. Protus and Hyacinth meet the same fate. The story, embellished with extraordinary adventures, could be distantly inspired by historical figures. The tombs of the martyrs Protus and Hyacinth were indeed found in a catacomb in the 19th century; one of them was intact, containing remains and bearing an inscription. Philip could have been inspired by a prefect of vigils (in charge of firefighting in the Roman Empire) who travelled between Alexandria and Rome.21 We do not know if a person named Eugene or Eugenia ever existed; however, the figure of Saint Eugenia was popular all through the Middle Ages in the churches in Ravenna in Italy, in Poreč in Croatia, and later in Burgundy and in Catalonia, where she inspired sculptures and alter paintings.

On the Byzantine side, Matrôna de Pergé is known for founding a monastery that bears her name, Matronès. After leaving her husband for asceticism, Matrôna passed as a eunuch by the name of Babylas. Later, Matrôna reverted to her feminine name and life to found a women’s monastery, in which the nuns wore masculine clothes. Her adventurous life was written down in the 5th century and was read and re-read in the monastery.22

After leaving her husband for asceticism, Matrôna passed as an eunuch by the name of Babylas. Later, Matrôna reverted to her feminine name and life to found a women’s monastery.

Also in the 5th century, Theodora·os, known as Saint Theodora, was a popular figure whose life story was often told and retold. A married woman, she commits the sin of adultery under the influence of the devil. Her remorse brings about a gender transition and a new name: Theodoros. Falsely accused of seducing a woman who becomes pregnant, Theodoros says nothing to exonerate himself and takes care of the child, in a form of adoptive trans parenthood. A letter discovered after his death tells the whole story and sheds light on the false accusation of paternity.

Much later, in the 12th century, in the Empire (modern-day Germany), an attempt was made to canonize a person named Joseph, whose sex assigned at birth was discovered only after death, at which point he was renamed Hildegonde. The similarity with well-known cases of sainthood gave monastic leaders the idea to canonize Hildegonde as the first saint of the Cistercian order. These cases, sometimes rewritten, sometimes inspired by real people, bear witness to an imaginary in which gender transition itself is a reason for sainthood. Inspired by a Christian ideal of the first centuries, which aimed to transcend social norms and achieve real equality beyond the gender binary, these lives have for centuries conveyed a model of trans holiness, which, while it corresponded less and less to an increasingly binary society, advocated ascetic transcendence. These stories continued to be told in legends such as Jacobus de Voragine’s Golden Legend (which includes five trans saints, to be celebrated throughout the year) and depicted in paintings and sculptures ornamenting the walls of churches, such as those in the Basilica of Sainte-Marie-Madeleine in Vézelay, which show the trial of Eugeni·a·us.

These cases, sometimes rewritten, other times inspired by real people, testify to an imaginary in which gender transition itself is a reason for sainthood.

This medieval trans sainthood, whose impact was significant in its time, was exclusively transmasculine, as it existed in an unequal belief system in which the masculine prevailed over the feminine. But it is also the sign of a world in which porous and plastic categories were not always as restrictive as people in later centuries would have us believe. Within trans history, which is mostly riddled with intolerance and repression, trans sainthood appears like a ray of light that, despite everything, opens emancipatory perspectives. Gabrielle Bychowski, pioneer of trans medieval studies, describes them as stained glass windows: “Each facet of the glass is both a window and a mirror. And both the mirror and window are hard for many to face. It may show a window into the wisdom and beauty of trans life one is not willing to see. […] Yet each piece of the stained glass window is also a mirror. And it may reflect back to us long existing prejudice and ignorance.”23

Perspectives for a long-term history

What contributions can these accounts of medieval trans saints make to the history of gender and sexuality? Thinking from the point of view of premodern categories helps us to undo ideas that are profoundly ingrained in us, such as the biological sex binary, that have been naturalized in the West, but that do not correspond to the experiences of all individuals, nor to the totality of social structures and imaginaries on the planet. And we are perhaps at a moment in which it no longer corresponds to younger generations’ aspirations toward equality. Could a society that does not promote this distinction between sex and gender allow us to think beyond norms in the future? The role of research is to complexify our relation to the world, which certain discourses render terribly binary and simplistic. It seems to me that studying a long-term history of gender from a trans perspective will enable us to broaden the scope of future developments, because at present, the long-term history is that of a gradual loss of understanding of the meanings of gender fluidity developed at certain periods, particularly in early Christianity. By studying the moments in which the binary structure fails to define people, we can bring to light historical “gender regimes,”24 which have evolved over the centuries and are destined to continue changing.

Thinking from the point of view of premodern categories helps us to undo ideas that are profoundly engrained in us, such as the biological sex binary.

Translated by Fig Docher

This article was first published in French in La Revue du Crieur, n° 22, 2023. We thank La Revue du Crieur for the authorization to publish and translate it.

Notes

- Le Roman de Silence, in Récits d’amour et de chevalerie, Paris, Robert Laffont, 2000, p. 518. For a recent analysis, see Masha Raskolnikov, “Without magic or miracle, the Romance of Silence and the prehistory of genderqueerness,” in Greta LaFleur, Masha Raskolnikov, and Anna Kłosowska (ed.), Trans Historical. Gender Plurality Before the Modern, Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 2021, p. 178-206.

- This story only exists in a manuscript from the second half of the century: Nottingham, ms MILN6, f. 188-233r.

- See, notably, the debate between Karine Espineira, Ali Aguado, Laurence Rossignol, and Maelle Noir, that responds to the intrusion of a transphobic collective, la Petite Sirène, in the interministerial delegation against racism, antisemitism, and anti-LGBT hate (Dilcrah), in opposition to trans parenthood (by anti-trans activists received by the deputee Aurore Bergé) and the trap set for transfeminist activists by Amélie Menu, an antifeminist posing falsely as a documentarist. See especially « Comment les luttes trans bousculent les mouvements feminists » (“How trans struggles shake up feminist movements”), Mediapart, À l’air libre, November 17th, 2022. Éric Fassin, for his part, speaks of an “epidemic of transphobia” (Seminário internacional “Epidemia de tranfobia,” University of Rio de Janeiro, September 22nd, 2022), as a way of turning around the accusation launched by psychoanalyst Élizabeth Roudinesco in the show Quotidien, March 10th 2021, that made reference to an “epidemic of transgenders.”

- Since Magnus Hirschfeld’s Die Transvestiten (1925), many texts have been published, including those of Harry Benjamin and Robert Stoller. Pop culture has often made deviants and potential criminals of people not conforming to gender norms, such as in Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960). See the work of Karine Espineira, Transidentités : ordre et panique de genre. Le réel et ses interprétations(Trans Identities : Gender Order, Gender Panic), Paris, L’Harmattan, 2015.

- Sandy Stone, “The Empire Strikes Back: A Posttranssexual Manifesto”, Camera Obscura, vol. 10, no. 21992, p. 150-176.

- Karine Espineira and Maud-Yeuse Thomas, « L’observatoire des transidentités », <www.observatoire-des-transidentites.com/> ; see also Transidentités et Transitudes. Se défaire des idées reçues, Paris, Le Cavalier bleu, 2022.

- Susan Stryker, Transgender History. The Roots of Today’s Revolution, Berkeley, Steal Press, 2008.

- Leslie Feinberg, Transgender Warriors. Making History from Joan of Arc to Dennis Rodman, Boston, Beacon Press, 1996. See also Karine Espineira (ed.), Sociologie de la transphobie, Pessac, Maison des sciences de l’homme d’Aquitaine, 2015.

- Lili Elbe, Man Into Woman, online: Caughie, Pamela L., Emily Datskou, Sabine Meyer, Rebecca J. Parker and Nikolaus Wasmoen (ed.), Lili Elbe Digital Archive, www.lilielbe.org.

- In Linda ; or, Incidents in the life of a Slave Girl, chap. « New perils », 1861, analyzed by C. Riley Snorton, Black on Both Sides. A Racial History of Trans Identity, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 2020, p. 69.

- Gary Kates, Monsieur d’Eon Is a Woman. A Tale of Political Intrigue and Sexual Masquerade, New York, Basic Books, 1995.

- Document brought to light by David Lorenzo Boyd and Ruth Mazo Karras, “The interrogation of a male transvestite prostitute in Fourteenth Century London,” GLQ, A Journal of Gay and Lesbian Studies, vol. 1, 1995, p. 459-465, and recently by Gabrielle Bychowski, “The transgender turn. Eleanor Rykener speaks back,” in Greta LaFleur, Masha Raskolnikov, and Anna Kłosowska (ed.),Trans Historical, op. cit., p. 95-113.

- Guido Ruggiero, The Boundaries of Eros. Sex, Crime and Sexuality in Renaissance Venice, New York, Oxford University Press, 1985, p. 136.

- Jules-Étienne Quicherat (ed.), Procès de condamnation et de réhabilitation de Jeanne d’Arc, dite la Pucelle, Paris: Jules Renouard et Cie, 1841, vol. 1, 1841, p. 455.

- Marie Delcourt, « Le complexe de Diane dans l’hagiographie chrétienne », Revue de l’histoire des religions, vol.153, no. 1, 1958.

- Evelyne Patlagean, « L’histoire de la femme déguisée en moine et l’évolution de la sainteté féminine à Byzance », Studi Medievievali, vol. 17, 1976, p. 598-623.

- See Alicia Spencer-Hall and Blake Gutt (ed.), Trans and Genderqueer Subjects in Medieval Hagiography, Amsterdam, Amsterdam University Press, 2021.

- Stephen Davis, The Cult of Saint Thecla. A Tradition of Women’s Piety in Late Antiquity, Oxford/New York, Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Jérôme, Lettre XXII, 27, in Saint Jérôme. Lettres. Tome I, Paris, Les Belles Lettres, 1949.

- Georges Sidéris, « La trisexuation à Byzance », in Michèle Riot-Sarcey (ed.), De la Différence des sexes. Le genre en histoire, Paris, Bibliothèque historique Larousse, 2010, p. 77-100.

- Read Gordon Whatley, “More than a female Joseph? The sources of the late Fifth-Century passio sanctae Eugeniae,” in Stuart McWilliams (ed.), Saints and Scholars. New Perspectives on Anglo-Saxon Literature and Culture in Honour of Hugh Magennis, Cambridge/Rochester, D. S. Brewer, 2012, p. 87-111.

- Georges Sidéris, « Bassianos, les monastères de Bassianou et de Matrônès (Ve-VIe siècles) », in Olivier Delouis, Sophie Métivier and Paule Pagès (ed.), Le Saint, le Moine et le Paysan. Mélanges d’histoire byzantine offerts à Michel Kaplan, Paris, Éditions de la Sorbonne, 2016, p. 631-656.

- Gabrielle Bychowski, « Resonance, radiance, and glory : an invocation for trans saints », June 1st, 2021, online: www.thingstransform.com/2021/06/resonance-radiance-and-glory-invocation.html.

- “A gender regime can be defined as a particular and unique arrangement of sexual relations in specific historical, documentary and relational context,” Didier Lett, « Les régimes de genre dans les sociétés occidentales de l’Antiquité au XVIIe siècle », Annales. Histoire, sciences sociales, vol. 67, no. 3, 2012, p. 563-572.