ISSUE #6 – Talking Words

Creative writing practices at HEAD – Genève

Introduction

When I took over the direction of the ESBA (editor’s note: formerly the Geneva School of Fine Arts) in 2004, Hervé Laurent’s writing workshop had already been a singular and lively space there since 1999. Laurent and I met on this commitment and I have only been following it through, with conviction. The relationships between art and writing, between painting and poetry in the 20th century in particular, have been one of the areas of my work as an art historian. I also opened creative writing workshops at the École Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs de Strasbourg in 1996, entrusting them to Catherine Weinzaepflen and Jacques Demarcq. These workshops led to the publication, rather uncommon at the time, of several collections of students’ texts.

Very quickly, we set up a small working group including, in addition to Laurent, Carla Demierre, then an assistant in the writing workshop, and Alain Berset, the founder and director of the Héros-Limite publishing house, who was also involved at the school. We agreed on an active “policy” of inviting writers or artist-writers. After giving a workshop at the school, they would give a public reading of their own texts as part of the Voix Off series of events held at the Mamco, thanks to the friendly cooperation of Christian Bernard. It was also at this time that we created the Courts lettrages collection with Héros-Limite. Alain Berset, Hervé Laurent and I co-directed the collection. In reality, the choice of published authors was made by Laurent and Berset and my own role was mainly that of an initial supporter… The first book by Carla Demierre – who took over from Laurent as the person in charge of the workshop – was published there, as well as the texts of some twenty young graduates, some of whom, to date, have gone on to become Swiss literary or publishing figures (such as Julie Sas, Vincent de Roguin, Baptiste Gaillard, Anne Le Troter, among others).

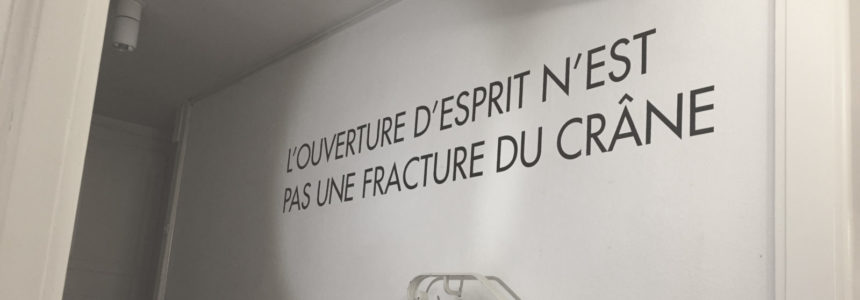

The idea that words are inscribed in contemporary art practices was thus very much anchored in the culture of the school. Carl Andre, for example, came to meet the students when Christophe Cherix showed his visual, typed poems in the Cabinet des Estampes. At the time, Jacques Demierre and Vincent Barras were already offering an astonishing work of sound poetry in the school’s sound workshop. In short, the question of writing and the idea of the text as visual or sound material was always running through the school. And this continues. These examples are testament to a singular and open creative space, at the crossroads of literature and the arts. Our alumni who have become writers have a singularity that is partly due to this origin of the text in the plastic arts, crossed from within by a visual dimension. They work the text as a texture, like clay. The text is a framework, a net with which to capture a part of reality. In their work, words appear to have a physical dimension. I would also like to emphasise that, beyond the singular field of creation they open up, the workshops hone a language skill that is now a key skill for all artists – and if we are talking about HEAD, for all designers – as an active vector of a way of thinking.

Within the art school, the work of writing opens up a particular space of freedom, giving licence that you wouldn’t usually allow yourself in a context more traditionally associated with literature. In an art school, the work of writing is an act of displacement; we work the text in a related territory. On the one hand, the text offers itself to very fertile logics of transpositions. On the other it is not, or is less, burdened with heroic, sometimes paralysing, figures. It is a creative space that can be inhabited more easily, free from the weight of genre and history. I hope that this feature reveals these remarkable sensibilities.

Jean-Pierre Greff